This 1838 lithograph by David Roberts exaggerates the size of the Egyptian Temple of Ramses III. The human figure at left front is only half the normal size, making the temple appear more monumental than it really was. (Illustrations courtesy Oriental Institute)

An Oriental Institute exhibit shows why images of ancient artifacts aren’t as accurate as we imagine.

Carved into a wall of Egypt’s Luxor Temple, a blurred tableau of religious offerings—its sandstone contours eroded after millennia of abuse from sand and salt—comes into sharp relief through a painstaking operation involving photography, draftsmanship, and scholarly deliberation.

A crumbling piece of plaster excavated from northern Iraq, showing the shadowy outline of three standing figures, metamorphoses into a portrait of Assyrian King Sargon II communing with a deity. That scene is then incorporated into an artist’s imagined replication of an intricate wall painting. In the process, the original object is transformed from rubble to living witness, and what began as a shard of a lost culture is elaborated into a rich narrative of a knowable past.

A crumbling piece of plaster excavated from northern Iraq, showing the shadowy outline of three standing figures, metamorphoses into a portrait of Assyrian King Sargon II communing with a deity. That scene is then incorporated into an artist’s imagined replication of an intricate wall painting. In the process, the original object is transformed from rubble to living witness, and what began as a shard of a lost culture is elaborated into a rich narrative of a knowable past.

The work of conjuring images like these is as much a part of archaeology as unearthing the objects themselves. Since the 19th century, reconstructed images of the ancient Middle East have been reproduced in texts, exhibitions, and popular culture. But rarely is the accuracy of those images questioned in a public venue. An exhibit at the Oriental Institute, Picturing the Past: Imaging and Imagining the Ancient Middle East, showcases the role archaeologists and artists play in creating popular perceptions of ancient history. The exhibit, which runs through September 2, illuminates how reconstructing ancient sites and artifacts relies not only on objective scientific information but also on hypothesis and speculation. One of its central questions is: how do we know what we know? It’s a problem that stalks all scholarly inquiry, but perhaps especially the study of the ancient past, whose evidentiary remains are fragmentary.

Archaeologists wrest history out of the ashes—and this is where the line between evidence and inference can be obscured, says Jack Green, the Oriental Institute’s chief curator. In recreating ancient artworks and monuments, “there has often been a strong desire to project an objective and authentic approach to the past,” Green writes in the exhibit catalog. “What is revealed through the study of these works, however, is how potentially misleading they can be.” Although artists and archaeologists may document the transition from raw observation to polished restoration, that information is rarely part of the final image, which is often treated as an empirical reference point.

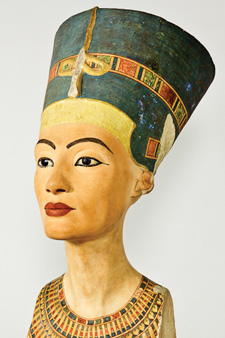

Picturing the Past calls attention to archaeology’s use of conjecture. For example, a widely exhibited copy of a bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti deviates from its source in a significant way: the original’s left eye is missing; in the replica it has been restored. “There is no trace of cement in the left socket” of the original, says Egyptologist and Oriental Institute research associate Emily Teeter, PhD’90. “So the eye was never inserted.” Compromising accuracy for aesthetics, the copies restored perfection to an icon of beauty.

“There’s never an attempt to mislead,” says Teeter, who cocurated the exhibit with Green and archivist John Larson, AM’01. “But as these images get reproduced, we get further away from understanding what was really there.” Although it challenges common ideas of what the ancient world looked like, the exhibit doesn’t dismiss the importance of reconstructive imagery. “There’s so much value to these images,” says Teeter. “The important thing to remember is that there’s speculation mixed in.”

Besides dispelling the notion that renderings of the ancient world should be taken as fact—including an inventory of the Oriental Institute’s own role in promoting the authority of reconstructed images—the exhibit also celebrates the creativity in retrieving an elusive past. The Sargon II wall painting, for instance, was excavated during an Oriental Institute expedition to Khorsabad, Iraq, and is part of the museum’s permanent collection. Architect Charles B. Altman created the painting restoration in 1935, combining his understanding of Assyrian religion, culture, and royal history with a more technical knowledge of Assyrian frieze motifs to produce an exceedingly detailed—and highly speculative—work of art.

Whereas decades ago archaeologists sought to align themselves with the hard sciences, today, says Oriental Institute director Gil Stein, many are beginning to embrace the use of multiple disciplines to imagine how ancient peoples lived. “Archaeology,” Stein says, “is at the meeting point of the physical sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities.”