Not long ago, College students and alumni could sum up the University’s take on non-academic pursuits thus: make your own fun. So they did, resulting in geek busing1 at the Shoreland, Sleepout2 on the quads, and the Scavenger Hunt pretty much everywhere else. But one house—Shorey, on the ninth and tenth floors of the recently demolished Pierce Hall—took “make” quite literally, ultimately giving birth to the now-legendary Shorey House maze.

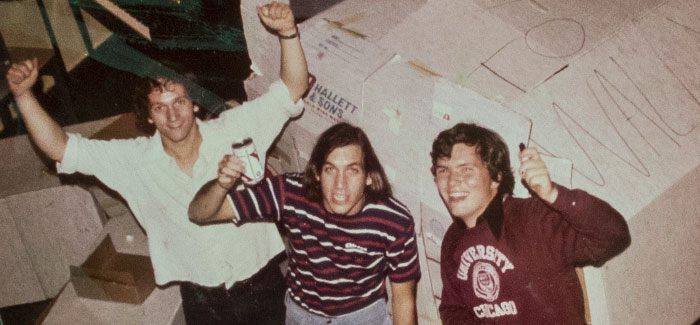

Its origins are hazy, which makes sense given that some posit it began life in the early 1970s as a beer maze.3 But by the 1973–74 academic year at least, the maze had evolved into a small network of large cardboard boxes in the Shorey House lounge, and there is later photographic evidence of a Halloween maze. Yet the tradition’s golden age seems to have begun in the late ’80s, by which point the 20" x 20" cardboard tunnel snaked maddeningly throughout both levels of the lounge.

“It got pretty serious the year before I was involved,” says Kristen Beaulieu (then Olson), AB’91, AM’96, who served as maze captain her first year. Lawrence Miller, AB’93, the 1990 maze captain, refers to it as an “arms race,” with the maze’s footprint—and complexity—proliferating year after year. Example: Beaulieu’s maze could be completed in 45 to 60 minutes; the average time in Miller’s maze, which filled every inch of the Shorey lounge, was three hours. Some never made it out the other side.

“No one died,” Miller assures. “Some did have to be cut out.”

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2048","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"429","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

What made it so confounding? “It was dark in a way beyond what you might think,” Miller says. The cardboard was taped together so tightly that no light could get in—not that there was much of it anyway, since the lounge lights were turned off. But the dark was just the beginning. The maze also featured hidden sliding doors, many of which had to be closed before another could be opened. By stacking tables, the designers could create sections with three levels, also with cleverly concealed doors. There were even two passages up to the lounge’s second level, one of which dropped you into a pit of packing peanuts.

The mazes weren’t without amenities. “Mine featured two or three rooms where people could just hang out,” Beaulieu says. Miller’s added forced-air ventilation, and the careful symmetrical construction ensured that maze goers couldn’t use air currents to tell where they were in the maze.

Obviously, these latter-day labyrinths weren’t built on a lark. Planning took months and in Miller’s year included the input of all three previous captains, including Beaulieu. “There was a big social factor to it,” she says. “All four maze captains hung out a lot.” Miller remembers sitting in the Pierce dining hall diagramming the most disorienting three-dimensional structures possible. Concentrating in physics, he approached it as a problem of “mathematical topography” to create “this gigantic nightmare of tunnels.”

The maze’s construction, done in total secrecy, took a week of pretty much 24-hour days. “You might go to classes, you might not,” says Miller. Sleep also became optional.

Then, over the course of two or three nights, 150 or so Shoreyites and other Pierce residents—more than half of the building’s population—took the plunge. Afterward, by order of the fire marshal, the captain and his team had a week to get rid of the now sweaty mass of cardboard. And falling afoul of fire regulations is ultimately what did the maze in. Several years after Miller was in charge, the maze was left up in hopes that it could be recycled, but adequate blue bin space was never mustered. A visiting fire marshal, finding the maze still standing several weeks later, put an end to the tradition.

Yet the legend lives on, a history of amaz—“No!” Beaulieu shouts. And with that, she reveals one part of the tradition that lives on: like uttering “Macbeth” during a production of the Scottish play, saying the “A-word” (in adjectival or any form) is strictly forbidden when discussing the Shorey House maze. The two captains will accept “awesome.”

Notes

1. Students taking the 1 a.m. bus back from the Reg during finals week had to endure taunts of “Geek!” shouted from hundreds of windows as they walked up the Shoreland’s long driveway. Their ignominy was softened by the knowledge that, come the new day, they would be busting the grading curve on their tormentors.

2. Before the Internet solved course registration and most of the other problems that plague humanity, College students hoping to get into popular classes would camp on the quads to be first in line for adviser appointments.

3. Beer mazes and towers—recently emptied containers placed in various geometric configurations—were both a form of creative expression and an inexpensive way to fill floor or wall space when you didn’t have a rug or Clash poster handy.

Video

All about UChicago’s unique College houses, the heart of our residential community on campus.