Award-winning game series The Last of Us follows Joel and Ellie after an apocalyptic pandemic has turned most people into hostile zombies. (Image courtesy Naughty Dog)

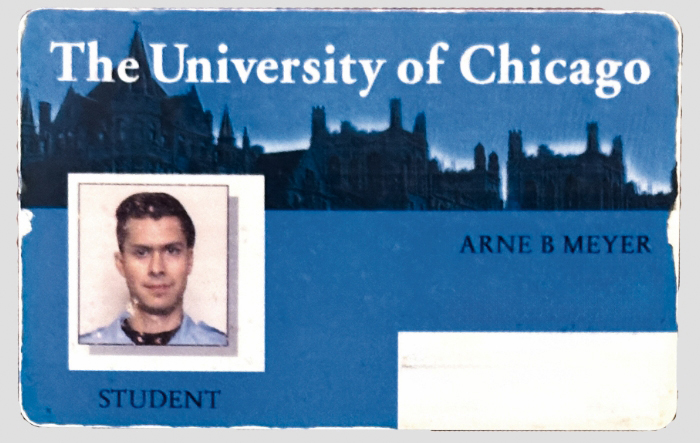

Arne Meyer, AB’00, of Naughty Dog studio, on the past, present, and future of the games industry.

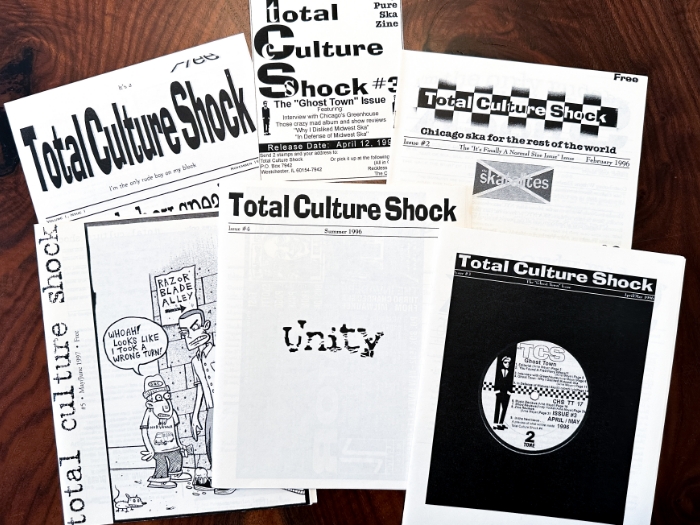

Long before UChicago had its first Media Arts and Design students or launched the Weston Game Lab, Arne Meyer, AB’00 (a public policy studies major), spent his days at the College reading film criticism, reviewing punk records, and publishing a zine called Total Culture Shock.

Meyer has worked at Naughty Dog, the video game studio known for The Last of Us and Uncharted franchises, for more than 15 years; he now serves as head of culture and communications. He joins us for a conversation on internet communities, interactive media, and gaming on a desert island. This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did you end up in video games—and at Naughty Dog?

A lot of young people think you have to be a programmer or a game designer to work in video games. I felt the same and never really explored what other avenues—what other jobs—there might be within the industry.

I ended up working for a public relations company, for the department that worked on digital communities and built websites and did digital PR. I think having this broad education gave me the ability to work at a PR firm in tech, even though I didn’t graduate in communications or some aspect of web design. The firm ended up pitching the campaign for the original Xbox launch. That’s what sent me off working in video games. Then a former colleague recommended me for my first position at Naughty Dog. What attracted me to Naughty Dog is they were doing very narrative-heavy, character-driven games.

Were any of your College courses helpful for your career?

A film studies class with Tom Gunning [professor emeritus in Cinema and Media Studies]. I got exposed to David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson’s Film Art: An Introduction [first published by Addison-Wesley in 1979] and the serious criticism of media.

I took Michelle Jensen’s [PhD’00] Third Wave Feminism and Girl Culture. I was already in the punk subculture, so we connected on the fact that I liked self-publishing and writing zines. We explored grassroots communities and understanding different perspectives and raising underrepresented voices.

My final paper in public policy on the National Endowment of the Arts asked if the federal government should fund controversial art. But it made me think, what are some career pathways that I could merge?

Do you think video games are art?

Games are a form of creative expression, and that exists in every art. Art can be commercial, it can be entertainment, it can be serious and introspective, it can be funny, but it’s always a form of creative expression. And games are just another avenue for that.

Games have only been around for 60 or 70 years—the medium’s still maturing. But they are an opportunity to explore personal or political themes, to have a message.

There are so many things that are adjacent to games that are also art. People take screenshots from games and turn them into their own pieces of art with incredible lighting. There are ways that people are reinterpreting and remixing, which is the core of what art is: to build on top of what’s happened before and to remix it and to reinterpret. You can make a statement, you can explore personal, political, whatever it is. That’s always been at the core of art, and games are continuing that legacy.

In the games industry, we often struggle to feel legitimate in the cultural consciousness, even though we are bigger than the movie industry in pure dollar terms. So many people play games—including people who don’t even realize that they’re gamers, because they’re playing Candy Crush on their phone.

We have games that are providing underrepresented points of view. We have games that are changing people’s minds and perspectives. But when you look at the cultural commentary on games, it feels like we’re not yet legitimized by the serious press or in organizations and award shows. That’s the next step.

What are your thoughts on games receiving social and scholarly analysis? Can they hold up to this analysis?

Games started in academia with a bunch of people in the lab building a game because they could on early computers. Games didn’t necessarily come from an expressionist medium. I think we might still be figuring out what the language is for us to look at games beyond viewing them as products.

For a long time it’s been, let’s review a game and tell you the graphics are great and the gameplay is great, and here’s a score because it was a business to begin with. But as games are maturing, as people who make the games are maturing, we’re starting to create the framework that’s needed to break down what’s happening in game and really understand how to analyze them. It’s great to see schools like the University of Chicago lean into that more.

What kind of responsibilities do creators have when making games?

To be authentic and explore what is meaningful to you. Don’t try to make something purely commercial. I mean, there’s room for that. But how can you be true to yourself in what you’re trying to explore?

Our constituency is changing—not only our audience, but the people we work with. People who are thinking about broadening accessibility, or about games that represent the world around us more accurately, are starting to be in positions of influence.

I’m now in a position to help make that happen. To help communicate the type of accessibility features that we’re putting in games so that more people can play our games. To make sure that our hiring processes don’t have bias in them, that we’re attracting a diverse population of candidates.

I’m fortunate because I care about those things, and I’m in a position where I can start effecting that change. And I think that exists everywhere in the industry. We’re opening up our own perspectives for what our communities want and need from us.

Which game first made a lasting impression on you?

Legend of Zelda on the original NES [Nintendo Entertainment System], because there was a narrative to it. I remember building maps of the dungeons and selling them to people at school. I was enjoying it with my mom. I loaded up the cartridge recently and her “save game” is still there.

Do you have any games that you really enjoy that people might be surprised by?

Games that have some sort of postmodern or absurd theme, like No More Heroes. For me, it’s finding those games that are experimental or untraditional that I really, really love. I work for such a mainstream entertainment medium, but I love these crazy, innovative games.

What’s your desert island game?

Something from the Soulsborne series—all right, I’m just going to pick Bloodborne, I love the Lovecraftian sort of Eldritch horror aspect of it. I’ve already put so many hours into it, so I can see myself playing that game for a very long time.

I’ve always wanted to get into those games, but I’ve seen how difficult they are, and I’m like, maybe that’s not for me.

If you’re on a desert island, you have all the time in the world.

Right, that’s true.

I’m the same way. I’m terrible at those games. But I love living in that world.