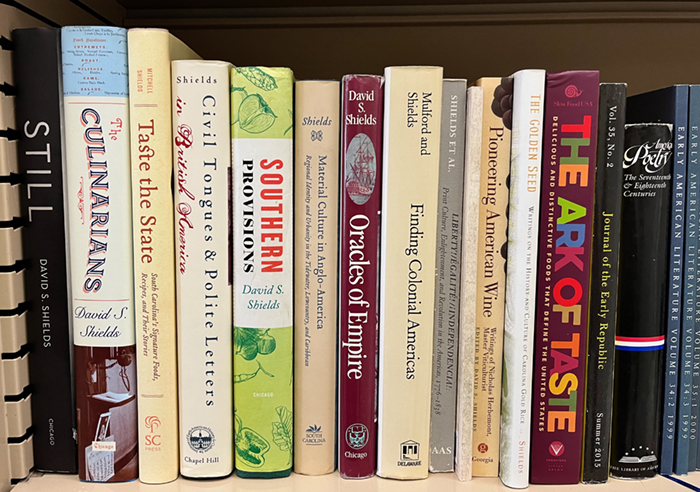

The search for lost heritage crops has led David Shields, AM’75, PhD’82, to farms across the US South and farther afield. (Photography by Kim Truett/Carolinian)

How literary scholar David Shields, AM’75, PhD’82, came to rediscover dozens of forgotten crops and preserve Southern culinary heritage.

It’s a sunny summer day. I’m driving through the campus of the University of South Carolina, in Columbia, with David Shields, AM’75, PhD’82. We pass the building where he has been a member of the English department faculty for the past 21 years. Soon he will vacate his office there, give away many of his books and journals, and sail into retirement. But, Shields points out, “there’s no retiring from the life of the mind.”

We reach Blanding Street, site of Historic Columbia, a preservation nonprofit offering education programs and events. There, Shields walks me through the young fruit trees of an heirloom garden—some of which he himself saved from oblivion. He reels off facts about each individual plant. There’s the Early Crawford peach (“the leading spring market peach in the 19th century”), the Shui Mi Tao peach (“the reason Shanghai became a city”), and the Lemon Cling peach (“favored for brandy and canning”).

A group of trees with branches that fall in wide green ribbons about their trunks are Hicks Everbearing mulberries, he says, developed around 1813 by horticulturist and master vintner Nicholas Herbemont. Other mulberry trees were intended to feed silkworms; Herbemont’s were not.

“It was known as the hog tree,” Shields says as he touches the branches. “It’s everbearing because it drops fruit for three months. An orchard of 46 trees an acre could feed 100 hogs, mostly guinea hogs, for half the time needed to prep them for market. And chickens as well—it shaded chicken yards. Mulberry-fed pork and chicken meat was supposed to be wonderful.”

The Hicks tree was common on farms throughout the Southeast until around 1890, when grain became the feed of choice for pigs and poultry. Thereafter, it all but vanished. But in the winter of 2016, Shields and a horticulturist from Historic Columbia, Keith Mearns, traveled to a 150-year-old mulberry grove outside Mount Olive, North Carolina, and took cuttings from one of nine extant trees. Mearns managed to root the cuttings, and now they can be seen growing in Historic Columbia’s garden.

Shields’s success in tracking down supposedly lost cultivars—plants produced through selective breeding like the “hog mulberry”—has made him one of the country’s foremost culinary historians. Most of the neglected cultivars he finds are hardy, able to withstand drought and deluge, and more nutritious and tastier than today’s varieties. Once found, they are brought back into production. Some, such as Carolina Gold rice, are nationally available. Others, such as rice peas and benne, are maintained by heirloom seed companies for produce stand cultivation by farmers and home gardeners.

In addition, Shields has learned about soil composition, the identity and location of the plants’ farmers, recipes incorporating the plants, the people preparing those dishes, and the places where the dishes are traditionally served, be they homes, restaurants, or banquet halls.

“David’s contributions are difficult to translate in a simple sentence because it’s two decades of multidisciplinary work that’s groundbreaking worldwide,” says Glenn Roberts, who specializes in recovering, growing, and marketing old grains and cereals. “Finding lost foods and assisting in their path to recovery is what he does. He operates with the idea that he’s finding foods that need to be on the American table, and there’s no one else working like this in the country.”

But how did a tenured English professor come to be stomping around in mulberry groves?

At a 2003 conference in Charleston, South Carolina, titled “The Cuisines of the Lowcountry and Caribbean,” Shields had a watershed moment that would propel him deep into the culinary realm. He had just concluded a lecture to an audience of chefs, historians, farmers, and food producers when he was approached by the grain-loving Roberts, founder and CEO of Columbia-based Anson Mills. Roberts’s company grows, mills, and markets Carolina Gold rice, which was the primary rice grown in the United States until the Civil War. Its origins aren’t certain—West Africa? Madagascar? Asia?—but it fell out of favor when other strains of rice appeared that could be harvested by machine. Carolina Gold rice became little more than a missing ingredient in old recipes.

Roberts was instrumental in its recovery. By 1998 a disease-resistant variety of Carolina Gold rice was being grown organically in Texas, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Roberts isn’t done with rice. His company is attempting to rescue other early cereal cultivars and legumes from the doldrums of neglect and to restore them to production.

At the Charleston conference, Shields’s use of “cuisine” troubled Roberts. Because, Shields learned, what he had called a cuisine “wasn’t a cuisine, it was a cookery. To have a cuisine, you have to have local ingredients, and we didn’t have those.”

Roberts asked Shields if he would research the crops that had brought worldwide praise to Southern restaurants and chefs in the 1800s. Not realizing what a quagmire he was entering, Shields said yes. How difficult could it be?

A self-described archives rat, he is as relentless a digger as a Jack Russell terrier. And he was accustomed to methodical forays into the obscure. For his book Oracles of Empire: Poetry, Politics, and Commerce in British America, 1690–1750 (University of Chicago Press, 1990), Shields exhumed a raft of forgotten poems, most of which likely hadn’t been read in a century. Besides, he had already spent who knows how many hours reading horticulture books and cookbooks at the South Carolina Historical Society, learning what people were planting, preparing, and eating in the state before the Civil War. He figured he’d be finished with Roberts’s request in a couple of weeks.

“I didn’t know then that I had made a deal with the devil,” Shields says with a laugh. “I learned how much I didn’t know.”

At the time, Shields was teaching at the Citadel in Charleston, but in 2004 he accepted a position at the University of South Carolina. He moved to Columbia with his family and continued his research there. In the basement of USC’s Thomas Cooper Library, he delved into dusty antebellum agricultural journals, plantation records, and seed catalogs. Reading books on botany and agronomy, he learned how farmers grouped crops to ward off pests or to improve the soil. He discovered that certain old grains develop elaborate roots that can extend as far as 50 feet, pumping sugar into the soil and extracting micronutrients, which translate into richer, fuller flavor.

“I realized my ignorance was profound about Southern ingredients,” Shields says. “We had lost so much. We didn’t even know what we had lost. And I didn’t understand why 19th-century farmers were growing certain things with other things.”

He spent three years in Thomas Cooper’s stacks, where he studied books and manuscripts detailing crop rotation and soil health. Outside the library, Shields was involved with the nonprofit Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, which he had helped organize in 2005. (After he tasted the cooked rice, he was all in. The taste and texture were enormously satisfying, reminding him of the congee he ate as a child in Tokyo, where his father worked in the early 1950s.)

In 2009 Shields agreed to become chair of the foundation’s board, a position he still holds. The Carolina Gold Rice Foundation’s goal is to find, revive, and restore to Southern cooking an entire repertoire of landrace grains, vegetables, and fruits. (A landrace is a cultivated variety of plant suited to local conditions.)

After three years of research, Shields had compiled a list of 45 cultivars that had been served on South Carolina dinner plates for 50 years or more throughout the 1800s. He found that in the years after the Civil War, Southern farmers had started truck farming and sending produce to Northern markets. They chose prolific, shelf-stable, pest-resistant varieties that were profitable but often not the tastiest. And to increase yields, farmers began applying commercial fertilizer to fields they had once fertilized with manure, changing the chemistry of the soil and the taste of the foods they produced. While in prescientific cultures wholesome flavor was the primary indicator of nutritive value, Shields points out, in the 20th century new cultivars weren’t even tested for flavor, so strong was the emphasis on crops’ disease resistance and productivity, and farms’ ability to transport and process them.

As monocultures thrived and expanded, flavor and genetic adaptability suffered. By 1890 many long-used ingredients had all but disappeared. Only two, it seems, have remained unchanged: okra and collards. The foundation focused on finding and restoring the other 43, which had been perhaps unwisely abandoned.

Much as historic preservationists think a neglected building should be restored and used, culinary historians believe a neglected cultivar ought to be grown and eaten. In the past 15 years, Shields and a team of geneticists, horticulturists, seed savers and sellers, home gardeners, and farmers have found and brought into production all but four of the 43 plants he sought.

“David has been transformative in what we know now about Southern cooking,” says Sarah Ross, editor of Social Roots: Lowcountry Foodways, Reconnecting the Landscape (University of Georgia Press, 2024) and a board member of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation. “He never extrapolates, never jumps to a conclusion. He’s extraordinarily accurate, and he imparts not just information but curiosity.”

Finding plants that have gone missing is a little like searching for a beloved Irish uncle who stowed away from Derry to Boston and then lit out for Alaska. Shields and Roberts have checked seed banks, seed saver websites, and germplasm catalogs—where Carolina Gold rice survived—and in this way have found a few cultivars. But most of the sleuthing has meant talking with county extension agents and agricultural experts from other universities, traipsing through fields and forests, visiting home gardeners who have been saving seeds for generations, finding mislabeled items, or even traveling overseas.

Take watermelon—specifically the Bradford watermelon, known for its gigantic size and lip-smacking sweetness. The year after the Confederacy’s defeat, farmers shipped Bradfords and other Southern melons north to receptive markets. They were tastier than what was typically found in, say, New Jersey. So demand was high.

But the Bradford’s soft rind made it a poor traveler. It was supplanted by less delicious varieties with thick skin that held up to boxcar shipping.

In early 2009 the foundation began searching for the Bradford and for two other Carolina melons, the Ravenscroft and Odell’s White. Shields knew from research how important the Bradford had been to South Carolina cooks and chefs, who pickled the rind and made brandy and molasses from its juice. In 2013 Shields got an email from a South Carolina landscape architect, one Nat Bradford, who said an ancestor of his had developed the melon in the mid-1800s.

“My first impulse was I wanted to see proof—a photo, a seed. Then I wanted to make sure he was a true Bradford,” Shields says. “It was the genealogy that convinced me, because I had the lineage of the creator, Nathaniel Napoleon Bradford, down to the end of the 19th century. His family knowledge linked up with my list. … It was then that certainty and joy bloomed.”

In the winter Bradford drove to Columbia to show Shields a jar of seeds and some photos. The next summer, Shields went to Bradford’s farm and found the big melons growing in the fields there. Bradford later started selling them to brewers and food producers, and to restaurateurs like Sean Brock in Charleston, a James Beard Award–winning chef. Bradfords are now in ever-increasing demand.

Shields was involved in many other success stories. For example, the search for Moruga Hill rice, another “lost” food, took him nearly to South America. In 2016, with Charleston chef Benjamin “BJ” Dennis, he attended a rice symposium organized by ethnobotanist Francis Morean on Trinidad, off the coast of Venezuela.

Morean is one of many Trinidadians descended from a group of transplanted enslaved people who had once lived on Georgia’s Cumberland Island. In return for fighting in the War of 1812—for the Corps of Colonial Marines—the British government granted them freedom and land on Trinidad, where they settled and became known as “Merikins” (Creole for “Americans”). With them they took seeds for various crops they had grown during their years in captivity.Among these were okra, corn, and rice—including the Moruga Hill rice for which Shields had long been searching.

Morean had contacted Shields and Dennis to invite them to the conference and told them that he thought he had their rice. After their arrival, Morean took them out to the country, where they came to a farm. “I walked into the field,” Shields says. “It was stunning. You see the story made flesh.” There it was, a field of rice on the verge of full ripeness, birds roosting in nearby trees, ready for the feast. Farmer John Elliot ran his fingers through the rice. There were the long, spikey awns that once prompted the Low Country name “red bearded rice.” The stems were not quite six feet tall, shorter than Carolina Gold and less likely to blow down in storms.

Another find was a lost ancestral North American peanut. For much of the 18th century, the Carolina African Runner peanut was used to make groundnut cakes, one of Charleston’s many signature dishes, sold by African American women for a penny. When the Spanish and Virginia peanuts edged out the Runner peanut, the groundnut cakes were gone. And yet, in 2012, Shields was able to find 20 remaining seeds in a cold storage seed vault at North Carolina State University, where plant breeders had labeled them “Carolina No. 4.”

He brought the seeds to Clemson horticulturist Brian Ward for propagation. Twelve sprouted, and when, in the summer of 2013, the peanuts blossomed, Shields and Ward knew they had revived the Carolina African Runner. It replicated the features of a specimen collected from enslaved people in Jamaica by Sir Hans Sloane in the 1680s that is now preserved in the Sloane Collection at London’s Natural History Museum. By 2016 those 12 peanuts had become 15 million, and farmers were growing them commercially. The Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, Anson Mills, and the South Carolina Peanut Board are funding the project.

Angie Lavezzo, of the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association in Pittsboro, North Carolina, knew that Shields had been searching high and low for three years for Cocke’s Prolific White Dent corn, developed in the 1800s by General John Hartwell Cocke of Bremo Plantation in Virginia. Lavezzo spotted someone selling “Cox’s Prolific” on Craigslist and alerted Shields. Together they traveled to Landrum, South Carolina, where they found Manning Farmer and his son Darrell; their family had been growing the corn since the 1930s, taking care with planting and seed selection. This particular corn has stalks 10 to 12 feet high that produce two to four ears, as opposed to one ear for other varieties. Manning Farmer’s seeds led to Cocke’s revival. It’s been introduced to growers and researchers around the country and is now grown at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

When Shields received tenure in the Citadel’s English department, he had spent more than 10 years focused on the history of writing. But “as a scholar, I didn’t want my life to be contained in six inches of a library shelf,” he says. He decided to branch out and develop an expertise in each of the five senses.

For hearing he created an archive of rare Russian piano scores composed between 1870 and 1930, now housed in the University of South Carolina’s Music Library special collections. Shields loves the piano. Recently, while I was visiting, his wife, Luci, could be heard at the keyboard, practicing the hymns she would soon play at a funeral service. It’s easy to believe she trained at the Eastman School of Music. “When I was thinking of marrying,” Shields says, arching an eyebrow, “playing the piano was a requirement.” He laughs.

For touch he studied karate, hoping to find a kind of body consciousness and sense of space. He practiced Wado Ryu karate for 15 years, until he was 55. It gave him “a heightened sense of where, how close, how dynamic things were around me.”

For sight Shields began gathering information on performing art photography: performer portraits and production stills for the Broadway stage and for silent movies. Because 70 percent of silent feature film prints have perished, stills are the only surviving visual record of these creations. He eventually wrote Still: American Silent Movie Picture Photography, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2013. He maintains an online archive of late 19th- and early 20th-century Broadway photography and photographers and has an extensive photo collection of theater stars and casts.

In his home office he places a high stack of these photos, encased in hard plastic sleeves, on the desk in front of me. When I ask about one, he tells me the woman pictured, Maude Branscombe, couldn’t act, sing, or dance but was placed on stage simply because she was lovely. An 1882 photo of Lily Langtry, with her wasp waist and languid expression, shows how alluring she was to her legions of fans. In addition to the larger photos, Shields has scads of “cabinet cards,” 4-by-6-inch photo cards featuring Broadway stars. At one time, fans bought these by the thousands.

For the final two senses, taste and smell, Shields turned his attention to food, work that still consumes him today. He has written papers and books, given lectures and talks, starred in indie films, and narrated animated shorts. For his work with saving old cultivars, he received the Southern Foodways Alliance Ruth Fertel Keeper of the Flame Award in 2016. He has twice been a finalist for the James Beard book award for reference, history, and scholarship. Taste has been a constant interest, even as he has ventured into other areas.

It doesn’t surprise those who knew him as a University of Chicago graduate student that Shields would spend years foraging for lists of lost foods in dusty journals. Before turning to plants, he had long been delving into other kinds of obscure, near-forgotten records. He wrote his doctoral thesis on early American spiritual diarists.

“In school David was really into cooking and looking into 18th-century foodways and home gastronomy, trying to connect literature and social and political history,” says Colby College professor Mary Ellis Gibson, AM’75, PhD’79. In the late 1970s she was coeditor, with Shields, of The Chicago Review. “David is omnivorously curious.”

When focused on a topic—early American epic poetry, photography, diaries, piano music, 19th-century chefs, a neglected cultivar—Shields finds primary sources and learns as much about it as he can. Luci is quick to point out that he does not have a photographic memory, as some friends assert. But she does concede that everything that interests him sticks to his brain. Off the top of his head, he can lay out the menu of Charleston’s Carolina Jockey Club Banquet from February 1860, provide details about the contributions of viticulturist Nicholas Herbemont, or sketch the life and career of stage and silent film star Jeanne Eagels.

In between his interviews and frequent travels, Shields still finds time to write. One representative book is Taste the State: South Carolina’s Signature Foods, Recipes, and Their Stories (University of South Carolina Press, 2021), written with chef Kevin Mitchell. Mitchell teaches at the Culinary Institute of Charleston. He says he and Shields “have been joined at the hip since 2014. He’s a brainiac with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. I can ask him any question, and he can give me an answer.” Shields wrote most of the stories in their book, while Mitchell provided all the recipes.

Taste the State is informative, the writing lively. On biscuits, Shields writes, “The star of breakfast, the partner of gravy, ham, and butter, the carrier of marmalade and fruit preserves, the biscuit has long been beloved throughout the South, and especially in South Carolina.” On gravy, he says it “is the most treacherous dish in the whole art of cookery, showing immediately the mastery or incompetence of the maker.” He and Mitchell recently finished another Taste the State book for Georgia, coming out this September, in which they reveal the secrets of chicken mull.

Shields’s most recent book is The Ark of Taste: Delicious and Distinctive Foods That Define the United States (Voracious, 2023), written with Giselle Kennedy Lord. Highlighting foods that were once deemed lost but have now been brought back into production, it takes its title and premise from Slow Food’s Ark of Taste project, a global register of the most historically resonant, flavorful, and imperiled foods. The book covers the American items in the Ark of Taste International catalog, now documenting online some 6,500 products from more than 150 countries: Arkansas Black apples, Maikoiko sugarcane from Hawaii, cassava leaf flour from Argentina, Sohshan wild strawberries from India, and on and on—“edible treasures,” in the words of the project’s website.

As chair of the Ark of Taste committee for the American South, Shields has been intimately involved in evaluating and creating nominations for imperiled American foods. The book relates how cherished foods were nearly lost, celebrates their qualities, and tells of their savers and guardians. It also poses the question of what other valuable ingredients need to be rescued and restored to kitchens across the United States to preserve their flavors and to secure their genetic heritage.

Shields’s work for the past 20 years suggests what can be done.

Rebecca McCarthy, AB’77, is a writer in Georgia and the author of Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers (University of Washington Press, 2024).