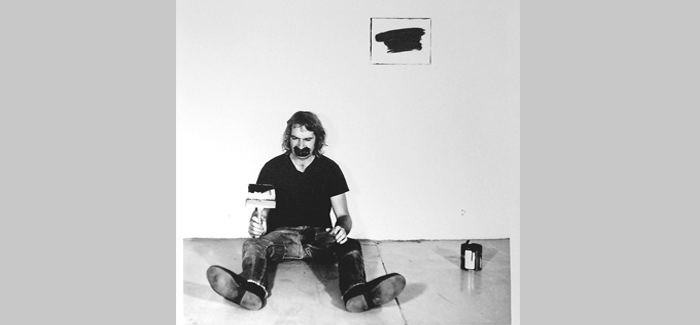

William Wegman’s 1971 photograph sends up the art establishment. (William Wegman, Artist, 1971, black-and-white photograph, 14 x 11 in. Courtesy of the artist and Marc Selwyn Fine Art)

A traveling exhibition explores California art’s experimental state of mind.

On a Smart Museum wall, Robert Kinmont is upside down. Eight black-and-white photographs show the artist performing a series of handstands. Starting on a rocky precipice, he moves down to a stream, a meadow, and eventually the forest floor. The images capture the spirit of California conceptualism from the late ’60s to the mid-’70s, said Karen Moss in an October gallery talk. An adjunct curator at the Orange County Museum of Art, Moss co-organized State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970, a traveling exhibition stopping at the Smart through January 12. Kinmont’s piece, like much of the art on display, she said, is “on the edge—it’s a little bold, it’s a little edgy, it’s a little dangerous, but it’s ultimately quite funny.” The exhibition includes installations, films, photographs, artists’ books, and posters, often documenting a performance or other ephemeral piece of art. California conceptualists eschewed traditional forms like painting and sculpture, said Moss, and often used multiple media within one piece. They sometimes riffed on art making and the role of established galleries and museums—for instance, a 1971 William Wegman photograph depicts the artist sitting on a studio floor, brush in hand and paint smeared across his face “in a mock abstract expressionist gesture.” Looking for alternative venues, some conceptualists took to the streets. For Chicken Dance, Linda Mary Montano donned a baby-blue tulle prom dress and a hat with feathers and a beak, dancing and, in the artist’s words, “performing spontaneous acts of ecstasy” across San Francisco. One documentary photograph captures her lying prone in front of the Reese Palley Gallery, “the important art gallery in San Francisco at the time,” said Moss. Montano’s antics, a protest against the gallery’s all-male lineup, illustrate two of the movement’s themes: feminism and using the body as material. Living in a state that was an “incubator for social change and youth-oriented counterculture,” Montano and other California conceptualists were driven to include social, personal, and political content, said Moss. In the last room a screen flashed images of public disruptions by Joe Hawley, Mel Henderson, and Alfred Young, who worked as a team. In November 1969 the trio arranged for more than 100 people in San Francisco to take cabs to the intersection of Market, Castro, and Seventeenth Streets and shot the jam from a helicopter and the street. Moss’s audience couldn’t help but laugh at the aerial shots of bumper-to-bumper cars. Like Kinmont, the trio carried out a provocative idea with a dash of wit.