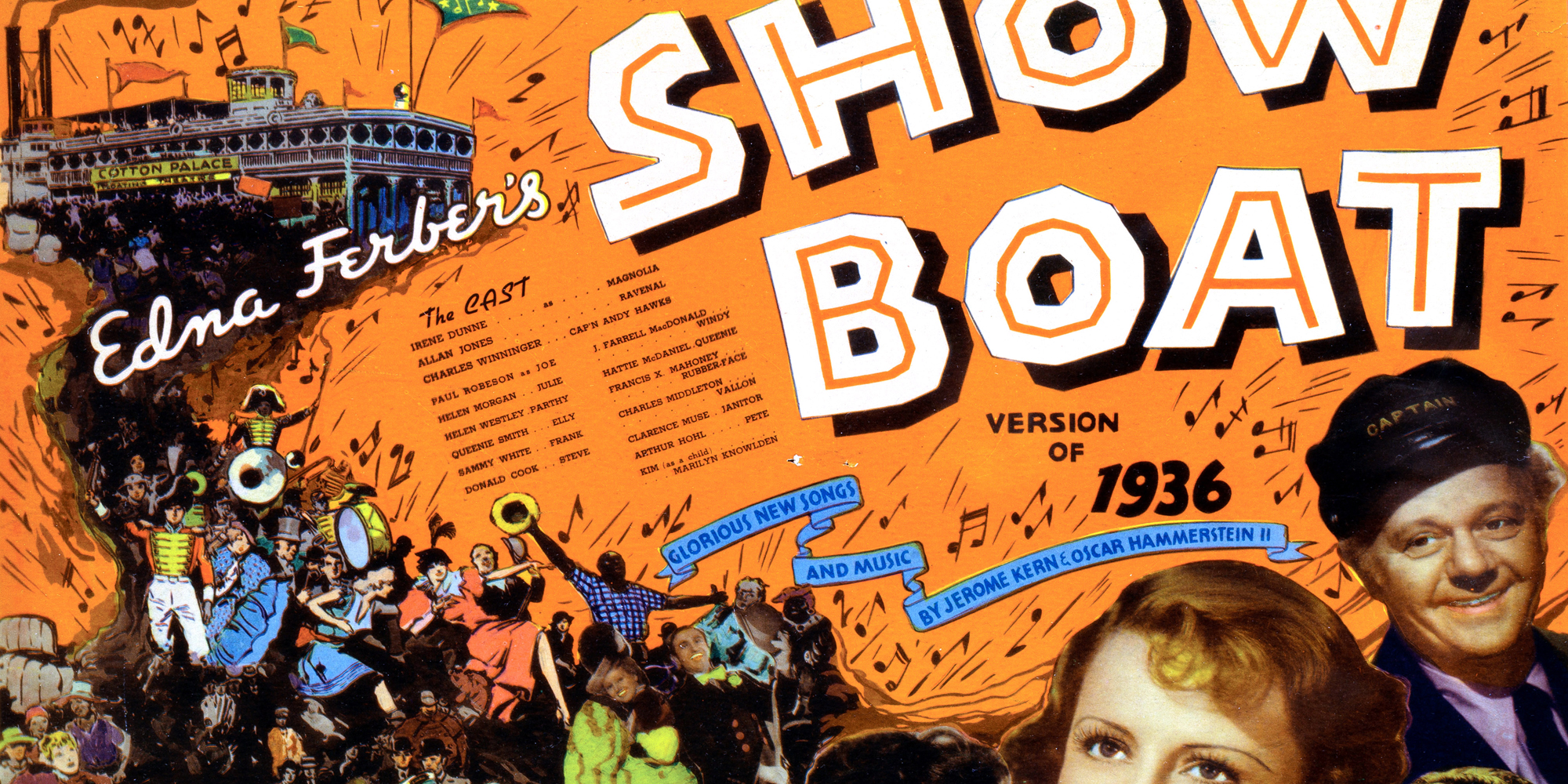

Thomas Christensen’s course is not intended to be a history of musical theater, though the syllabus goes from oldest (Show Boat) to newest (Hamilton). About a quarter of the students in the spring 2018 course were music or theater and performance majors. (Everett Collection)

Lights up on Thomas Christensenʼs Making and Meaning in the American Musical.

It’s the second week of spring quarter in Making and Meaning in the American Musical, and Thomas Christensen, the Avalon Foundation Professor of Music and the Humanities, asks the class what may be the central question for anyone who’s ever watched musical theater—and certainly for many people who dislike it—“Why is everyone singing?”

The class is discussing a scene in the 1936 film version of the Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein musical Show Boat. When the handsome riverboat gambler Gaylord Ravenal meets Magnolia Hawks, the riverboat captain’s daughter, they break into the song “Make Believe.” But why?

The song is about two people falling in love, and one student says the music “has this tendency to kind of jump-start emotional processes.”

“The fact that it was a duet kind of implies something intimate about it,” a classmate adds. “They’re already communicating—even though they don’t know each other, there’s a connection.”

Christensen reads Hammerstein’s lyrics: “Only make believe I love you. Only make believe that you love me. Others find peace of mind in pretending. Couldn’t you? Couldn’t I? Couldn’t we?” He reads a few more lines as the students giggle.

“It’s not exactly Shakespeare, is it?” he says. “But within those six lines or so, you basically have accelerated something that should take hours, days of getting to know someone, or maybe in normal life, weeks and months.”

He points out that earlier in the movie, several characters sing “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man.” Christensen borrows a term from film to describe the music in that scene: diegetic. The music is happening within the world of the show, and the characters know they’re singing. In contrast, “Make Believe,” like many romantic duets, is nondiegetic—the music is an expression of the characters’ inner thoughts, not part of the outer world they inhabit.

The music “sneaks up underneath you,” Christensen says, “and presumably the characters aren’t aware of it until they start singing. In a sense, this is just their emotional personae coming through.”

Music, he notes, is not only an emotional expression. It also tells the truth of the situation even when the action says otherwise. For example, at the end of the “Make Believe” scene, as Ravenal learns that the judge wants to talk to him, the music turns to a minor key, signaling something ominous lies ahead.

Over the quarter, the students analyze four musicals: Show Boat (1927), South Pacific (1949), Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979), and Hamilton (2015). They examine the cultural and historical contexts around each of them, focusing on social class in Sweeney Todd and race in the other three shows.

But the course is called Making and Meaning, and Christensen also wants the students to understand a little of the technical craft of creating a musical. In week six, after a discussion of song anatomy and Stephen Sondheim’s use of lyric and rhyme in Sweeney Todd, the class has a more creative assignment: write lyrics for their own musical theater number.

“A refrain is usually a great thing to have,” Christensen tells students when he hands the papers back, citing the repetition of lines in Sweeney Todd ( “Nothing’s gonna harm you”), South Pacific (“You’ve got to be carefully taught”), and Show Boat (“Can’t help lovin’ dat man”).

Overall, he found the students’ lyrics clever, and projects a few on the screen.

“The SOSC Class Song,” according to the student who wrote it, satirizes “the condescension that can be expressed in a SOSC class—the tension between the academic establishment and some students who might be less into it.” It begins with a student walking into class and Karl Marx chanting “Religion is the opiate of the people,” then proceeds to a duet between the student and a professor, with the rest of the class chiming in as a chorus. Like a UChicago version of “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” much of the song consists of lines like, “Buon giorno, Mr. Adorno / How do you do, Montesquieu,” and name checks Milton Friedman, AM’33, alongside social sciences staples like Adam Smith, Ayn Rand, Simone de Beauvoir, and Michel Foucault, before the bridge: “You’ll learn in SOSC class just how little you really know.”

Christensen repeats his advice about the refrain. Then, to illustrate how it might work, he sits down at the Logan Center penthouse’s grand piano to improvise a melody that sounds a little like “Food, Glorious Food” from Oliver!

Christensen had told students they could explain the plot and characters to provide context for their songs, and some “essentially sketched out a whole musical,” he says.

One of them has written both melody and accompaniment for his song from an imagined musical adaptation of Macbeth. Like West Side Story did with Romeo and Juliet, it borrows the ideas and plot of Shakespeare, but not the specific language.

The song comes near the end of the play, after Lady Macbeth has killed herself and Macbeth is plunging deeper into madness: “Everything I’ve longed for / Everyone I’ve wronged for / All my life prolonged for / This. / Meaningless.” Accompanied by Christensen on piano, the student performs the song for the class.

“I wanted to do something that was a bit like Sweeney Todd,” he says, “kind of this investigation of psychosis.” Christensen notes that the minor major seventh chord progression is sometimes known as the Herrmann chord, after film composer Bernard Herrmann, who used it to great effect in Psycho. He suggests a more gradual tempo acceleration in the accompaniment, and when they try it again, both think it works better.

The course requires each of the 25 students to perform an in-class interpretation of some part of a musical. Christensen, himself not a singer, permits those not musically inclined to act out a scene or deliver a monologue, but most of the enrolled students are comfortable singing, having performed in musicals in high school or elsewhere.

Today three students take on numbers from Hamilton, which the class will travel downtown to see on stage the following week. Many of them are already familiar with the songs; they nod along to “Helpless,” led by the character Eliza Hamilton, and mouth the words and backing vocals to “Satisfied,” a song/rap led by Angelica Schuyler, Eliza’s sister.

For the day’s final performance, the hip-hop-based “Guns and Ships,” sung by Aaron Burr, the Marquis de Lafayette, and George Washington, Christensen asks the class to yell out “Lafayette!” and “Hamilton!” at the appropriate times in the song. Even before that point, they’re snapping their fingers.

After the song ends with George Washington’s line, “The world will never be the same, Alexander,” students pack up to go, smiling.

Syllabus

Making and Meaning in the American Musical meets twice a week. The class sees film or video of three musicals and attends a fourth show live. Christensen first taught the course in spring 2017.

Sondheim is Christensen’s favorite musical theater composer; he taught Company in 2017, Sweeney Todd this year, and hopes to take the class to West Side Story in 2019. In addition to short writing assignments, including the original lyrics and a review of Hamilton, students submit a final paper discussing an element—such as a song, a recurring melody or lyric, or a character—from a musical of their choice that is not discussed in the course.

As a Signature Course—an elective designed to be an introductory level course but not a survey or beginning methods course—Making and Meaning is open to anyone. Both times it’s been offered, it has filled up immediately, even when the syllabus didn’t include a trip to Hamilton (made possible through funding from the College, the Course Arts Resource Fund, and the Department of Music, plus a $40 per student contribution).