Artist Regin Igloria’s mission is to expand creativity through the creation of books. (Photography by Chloe Hadavas, ’17)

A glimpse into the paper, thread, and artistry of community bookbinding.

When I knocked on the door of room 401 at the Logan Center for the Arts, Regin Igloria put down the stack of papers he’d been arranging. He hurried over, ushering me into the visual arts classroom where we talked as he set up his bookbinding materials.

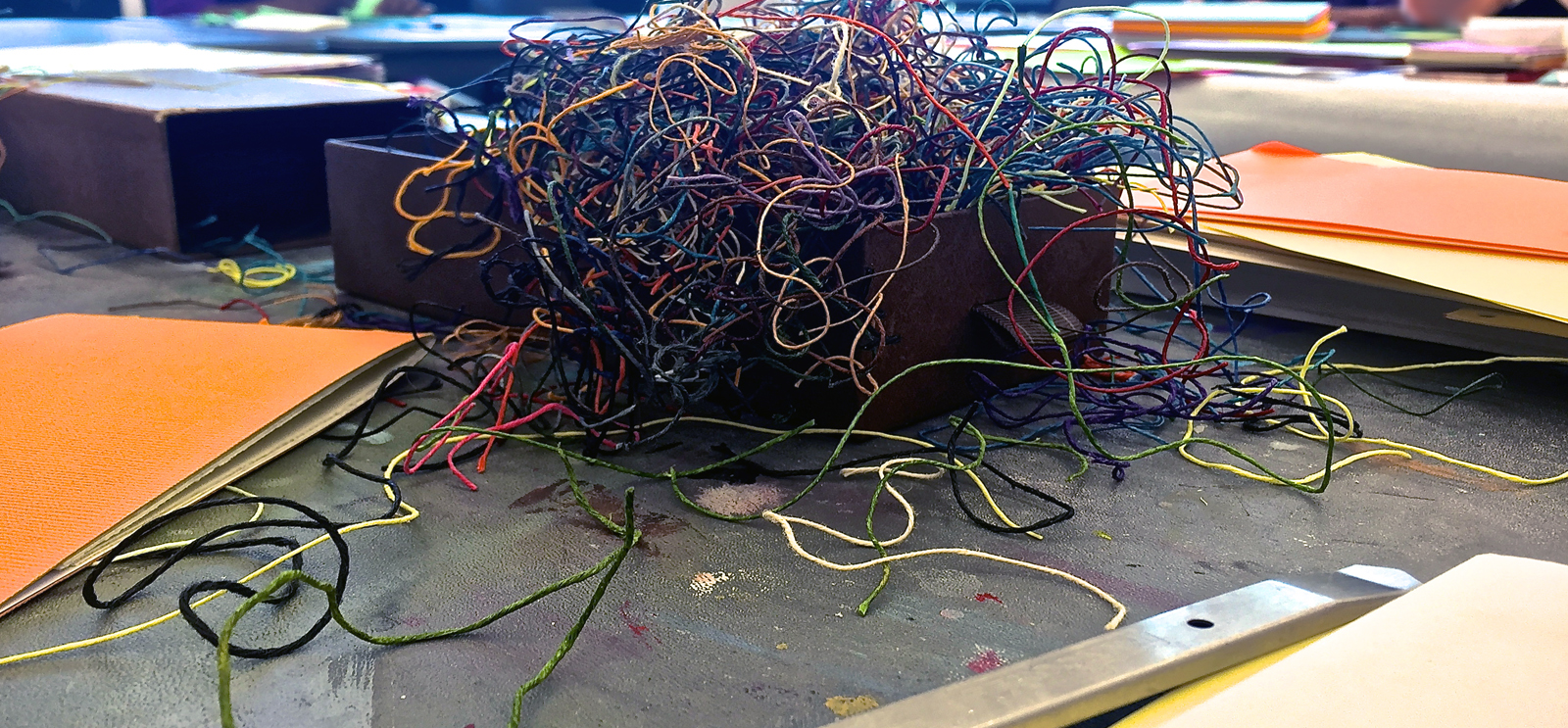

In the center of the room, Igloria displayed old books he’d made. Another table supported a treasure trove of tools: piles of patterned paper, scissors, craft knives, rulers, and needles. He laid out bone folders (made from the leg bones of animals), which would later help to crease paper, as well as spools of waxed linen thread, preferred by book artists for its thick coating.

By the time we had finished talking, the room was prepared to harbor a fully stocked bookbinding workshop, one of UChicago’s Suite 16 Summer Art Workshop Series held throughout the month of July. Organized by Logan Center Community Engagement for adults on the South Side, the series included 16 mini workshops in movement, storytelling, visual arts, and writing.

One might think of bookbinding as a solitary art, but Igloria, the founder of North Branch Projects, an Albany Park book arts organization, emphasizes its potential as a community discipline. “I saw books as a way to connect with other people,” he said. As an interdisciplinary artist—he works in painting, drawing, and performance art—Igloria found it difficult to share anything consistently recognizable with his loved ones. Making books helped his friends and family feel involved in the artistic practice: “It allowed my audience to literally have my works in their lap.”

As an educator, Igloria works with this same philosophy—one that stems from the communal aspects of the book format. His mission is to expand creativity through the creation of books. Most of the people Igloria works with don’t have an art school background, but he doesn’t consider that a barrier to making art.

He glanced at the clock with a worried look—it was exactly three minutes past the scheduled time, and only one person had arrived. Then 12 pupils entered the room in one fell swoop (they had been waiting together in the lobby). Though a diverse bunch, all were adults who resided in the South Side, and most had heard of the event from the Hyde Park Herald. They immediately began cooing over the book arrangement on the center table. Once seated, Igloria passed these books around, explaining the different Coptic, buttonhole, and pamphlet stitches that held them together.

As the books reached me, I ran my fingers along the bindings. One by one, the covers passed by me: part of a shoe box, a tea box, a brochure of a public garden, graphics from an old National Geographic issue, decorative fine arts paper. One book contained pages that looked like envelopes. The accordion books were not sewn at all, but held together by careful folding. The materials seemed endless, many of them recycled. Igloria stressed the freedom of the medium—“anything you can fold in half, you can sew into a book.”

With this introduction, the lesson began. We quickly learned how to measure the paper, make straight cuts, and use bone folders. We watched attentively as Igloria demonstrated the process of piercing holes in the folds with an awl, and sewing the thick thread through them to secure a sturdy binding.

After the demonstration, the attendees rushed to the center tables. Most grabbed their materials and hunkered down to work, but one woman lingered, contemplating which cover to choose. Flipping through orange polka dots, then pink, she finally settled on a faded lime green design.

We soon discovered that making the pamphlet book wasn’t particularly challenging. I worked slowly, leaving with two books—some made it out with four. The more elaborate bindings we had admired earlier still seemed beyond our capabilities, but Igloria assured us that the engineering was fundamentally the same.

As people began trickling out, Igloria implored us to write in our books. One of the most challenging things about teaching the book arts is not getting people to create books, he explained, but convincing them to use them. “There’s something about those empty pages that just makes it difficult to work in.”

He certainly had a point. I attended the workshop almost a week ago, and my books have since remained as decorations on my bedside table, untouched.