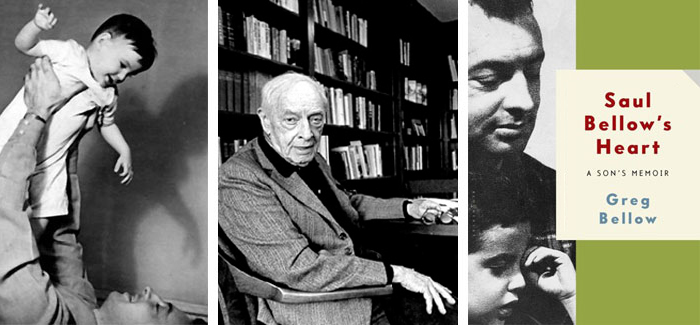

Saul and Greg in 1945. (Photo courtesy Greg Bellow); Saul in the 1990s at Boston University. (Photo courtesy Keith Botsford, CC BY 2.5)

Greg Bellow, AB’66, AM’68, reclaims his acclaimed father, novelist Saul Bellow, X’39, from those who would adopt him as their own.

On a visit to Chicago when I was eight, I witnessed a terrible argument, in Yiddish, between my father, Saul Bellow (X’39), and my grandfather. Driving away, Saul started to cry so bitterly he had to pull off the road. After a few minutes, he excused his lapse of self-control by saying, “It’s OK for grown-ups to cry.” I knew his heart was breaking. I knew because of the bond between my father’s tender heart and mine.

As Saul’s firstborn, I believed our relationship to be sacrosanct until his funeral, an event so filled with tributes to his literary accomplishments that it set in motion my reconsideration of that long-held but unexamined belief. As we drove away, I asked my brother Dan how many sons he thought were in attendance. His answer, literally correct, was three. I disagreed, feeling that almost everyone there considered him- or herself to be one of Saul’s children.

That first glimpse of the extent of Saul Bellow’s patriarchal influence awakened me to the impact of a literary persona I had assiduously avoided while he was alive. As an adult I turned a blind eye to his fame, which reached an apex when he received the Nobel Prize in 1976. After that I boycotted all events held in his honor. Saul became offended, but I felt the limelight contaminated the private bond I was trying to protect.

In the weeks following his death, I heard and read many anecdotes that claimed a special closeness with Saul Bellow the literary patriarch. I took them to be distinctly filial and soon came to feel that dozens of self-appointed sons and daughters were jostling in public for a position at the head of a parade that celebrated my father’s life. By now irked at the shoving match at the front of the line, I asked myself, “What is it with all these filial narratives? After all, he was my father! Did they all have such lousy fathers that they needed to co-opt mine?”

Before his death I had purposely placed the private man I did not want to share into the foreground. Infuriating as they were, the flood of posthumous tributes awakened me to the powerful effect of my father’s novels, to his status as a cultural hero, and to my lack of appreciation for the public side of him.

As I grieved and as the distinctions between the private man and the public hero were filtering through my consciousness, someone suggested I might find solace in reading Philip Roth’s (AM’55) Patrimony. I was deeply struck by a scene* in which the elder Roth catches his son taking notes, no doubt in preparation for writing about moments that Philip’s father considered too private to expose. I asked myself, “Has Philip no shame?” But Roth’s decision to write about his father’s last days forced me to think about what to do with the father who resides within me—a man whose deepest desire was to keep his thoughts and his feelings strictly to himself.

At a Bellow family dinner several weeks after Saul’s death, an argument broke out over the recently declared war in Iraq. My brother Adam maintained that our government’s actions were correct and legitimate, while I vehemently questioned the war’s rationale and its ethics. Later my cousin Lesha commented that watching us was like watching “young Saul” (me) argue with “old Saul” (Adam).

Our father was always easily angered, prone to argument, acutely sensitive, and palpably vulnerable to criticism. But I found the man Lesha called “young Saul” to be emotionally accessible, often soft, and possessed of the ability to laugh at the world’s folly and at himself. Part of our bond was grounded in that softness, in humor, and in the set of egalitarian social values I adopted. Saul’s accessibility and lightheartedness waned as he aged. His social views hardened, although he was, fundamentally, no less vulnerable. The earlier tolerance for opposing viewpoints all but disappeared, as did his ability to laugh at himself—much to my chagrin. His changes eroded much of our common ground and taxed our relationship so sorely that I often wondered whether it would survive. But Lesha’s comment highlighted the essential biographical fact: there could never have been an “old Saul,” the famous author, without the “young Saul,” the rebellious, irreverent, and ambitious man who raised me.

Writing my memoir, Saul Bellow’s Heart, which gives equal weight to the lesser known “young Saul,” the father I love and miss, meant going against a lifetime of keeping a public silence to protect his privacy and our relationship. But I wanted my children to learn about their grandfather. And I felt an obligation to open wide the eyes of my two younger brothers, who knew only “old Saul” as a father. Several recent scholarly articles of poor quality alerted me to the need for a portrait that reveals Saul’s complex nature, one written by a loving son who also well knew his father’s shortcomings. I have found Saul Bellow’s readers, toward whom he felt a special love, intensely curious about the man.

But what truly prompted me to write are the intense dreams that have taken over my nights. As my father’s presence faded from my daily thoughts, I was often wakened from an anxious sleep, desperately trying to hold on to fleeting memories. I took my nocturnal anxiety as a warning from a dead father who rouses his son in the darkness to preserve what remains of him before it is lost—perhaps forever.

Continuing to turn a Sammleresque blind eye to Saul Bellow’s literary fame would also have been to ignore lessons I learned right after my father’s death: That writing was his raison d’être, so much so that I honored his life by rereading all his novels in temporal sequence as my way to sit shivah (to formally mourn); that all the posthumous filial narratives were more than the grave usurpation I considered them to be at first; and that writing primarily from memory and about feeling suits me, a recently retired psychotherapist skilled in unraveling murky narratives. And perhaps most important, that my father looked most directly into the mirror when he wrote, providing me, through his novels, a window into his frame of mind and a reflective self he took pains to protect in life.

Despite my doubts about writing publicly, I determined to learn more about my father, to reassess my patrimony as a writer’s son, and to have my say. I can no longer climb into Saul’s lap as he sat at the typewriter, hit the keys, and leave my gibberish in his manuscripts as I did at three. Nor can I visit Saul in his dotage and stir up fading embers of our past. I can visit his gravestone and, in the Jewish tradition, put another pebble on it. But my “Pop” deserved more from his first born, as full and as honest a written portrait as I could render. Shutting my study door and struggling to find my voice on paper as I listened to Brahms or Mozart, as he did every day for more than 70 years, was as close as I could now get to my dead father.

Greg Bellow, AB’66, AM’68, was a psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapist for 40 years and remains a member of the Core Faculty of the Sanville Institute. He lives in Redwood City, California, and is married to JoAnn Henikoff Bellow, AB’66, AM’69. This essay was adapted from his book Saul Bellow’s Heart, published this April. Copyright 2013 by Greg Bellow. Reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury.

*Ed. note: It has come to the Magazine’s attention that this sentence, which appears in the book Saul Bellow’s Heart as well, refers to a scene that does not actually appear in Philip Roth’s Patrimony.