(Portrait photography by Rob Yelland)

Former attorney Phil Witte, JD’83, quit his job to be a full-time cartoonist. Now he has a book of cartoon criticism.

The single-panel gag cartoon is “unique in the world of humor,” Phil Witte, JD’83, and Rex Hesner write in Funny Stuff: How Great Cartoonists Make Great Cartoons (Prometheus Books, 2024). The genre is astonishingly spare: a single drawing, usually black and white, with a supershort caption—or no caption at all. And yet, they argue, “no other form of humor delivers the goods with such immediacy.”

Funny Stuff is not a how-to book, although its close analysis could serve as a road map for aspiring cartoonists (and if any of them become famous, “we won’t hesitate to take partial credit,” Witte and Hesner write). It’s more like a guide for deepening your cartoon appreciation—perhaps even becoming a cartoon connoisseur.

Funny Stuff grew out of a blog, Cartoon Companion. Hesner started it, then Witte joined in once they discovered their shared love of the genre. (Witte met Hesner, a jazz musician, at a neighbor’s party in Piedmont, California; at the time they lived a few houses apart.) In the blog they dissected, in obsessive detail, the cartoons in each issue of the New Yorker. Soon the cartoonists themselves were reading the blog, as was Bob Mankoff, who served as the magazine’s cartoon editor for two decades.

When Mankoff left the New Yorker and later became the head of the licensing site CartoonStock, he invited Witte and Hesner to write for it. That blog, Anatomy of a Cartoon, still appears sporadically. It was Mankoff who suggested that Witte and Hesner write a book together. He even supplied the foreword for Funny Stuff.

The book, Witte says, takes “an analytical approach, like a lawyer I guess,” while keeping a light tone so as not to kill the funny. It includes more than 100 cartoons (most licensed from CartoonStock) that many readers will recognize by the artists’ styles if not by their names: Charles Addams, Roz Chast, Emily Flake, Sam Gross, William Haefeli, Bruce Kaplan.

Funny Stuff also includes two cartoons by Witte himself. In 2012—living out the daydreams of untold numbers of lawyers—he quit his law job of three decades to become a full-time freelance cartoonist. He’s published work in the Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, the New Statesman, and the Times (London), among others.

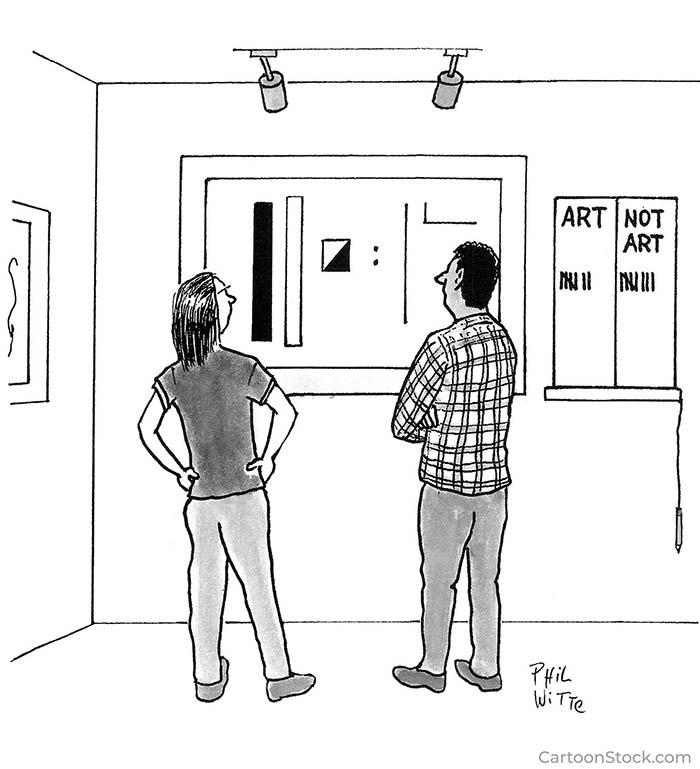

In chapter 7, one of Witte’s cartoons serves as an example of the “good news/bad news” gag. “You can afford to retire at 65,” a smiling financial adviser tells a middle-aged man, “but you’ll need to die at 70.” In chapter 8, Witte contributes a captionless cartoon to the debate about whether abstract paintings are art.

Witte worked in litigation after law school—“That was suited to my personality,” he says, “more competitive in some ways”—and ended up specializing in insurance law, becoming a partner at what was then Morison & Prough. Typical cases involved complex environmental claims or large-scale bank fraud. How complex, how large? “They had to have special courtrooms built just to hold all the lawyers sometimes,” he says.

Meanwhile, around 2004, Witte began drawing cartoons in his spare hours. While working on improving his drawing, he sold jokes to Bizarro, a daily single-panel newspaper cartoon by Dan Piraro. Witte also took classes in life drawing, but he isn’t sure they helped. More useful was simply “drawing more cartoons,” he says. “I’m talking hundreds and hundreds of cartoons.”

At work he was not funny. “The only funny person in the courtroom is the judge who makes a joke. Then everyone laughs,” he says. “It’s not appropriate for a lawyer.”

Funny Stuff reveals “the astounding rejection rate that cartoonists endure,” as Witte and Hesner put it. Even for regular New Yorker contributors, more than 95 percent of their submissions are rejected. “Frank Cotham, now one of the regulars, estimated that he submitted somewhere between 7,000 and 10,000 cartoons over a period of fifteen years before his first one was okayed,” they write. “For future cartoon editor Bob Mankoff, the number was about 2,000.”

An equally fascinating chapter explores how cartoonists get their goofball ideas. Roz Chast collects her own scribbles and sketches in a large shoebox, then sifts through them when it’s time to work. “It’s not efficient,” Chast told Witte and Hesner. “Some of … the best ideas I’ve ever had are probably lost in a dryer somewhere.” Other cartoonists read magazines and newspapers, turn on CNN, listen to or play music, ride the train, take a shower.

Witte’s method is to walk. After half an hour or 45 minutes, “I usually have an idea or two.” The gag comes to mind first, although he usually has a notion of what the drawing will look like. For example, “a dog talking to a person, or a whale,” he says, which probably means it will be underwater, “although not necessarily.”

EXCERPT

Eureka, It’s Funny: Idea Generation

By Phil Witte, JD’83, and Rex Hesner

With deadlines looming, how do cartoonists generate a batch of original cartoons every week? While some cartoonists do not actively, consciously think of ideas, others take a more structured approach: they mine ideas from well-worn pathways we’ve dubbed the “Idea Generator.”

Typical idea generators are cliché situations, stereotypical characters, characters we know and (mostly) love, personal characters, and lifestyle scenarios.

Cliché setups

The word “cliché” has a negative connotation. It normally refers to an overused or trite expression, like “happily ever after.” However, in the cartooning world, clichés—in the sense of a recurring graphic setup—can serve a useful purpose. Cartoonists know that if a reader doesn’t get the joke within a few seconds, the gag is a dud, and the reader will be frustrated. So cartoonists need visual shortcuts to speed up comprehension of their gags.

The cliché setup provides that shortcut, allowing cartoonists to present complex situations in a single frame. Upon seeing an image of Noah’s ark, Easter Island heads, or a patient on a psychologist’s couch, we need no further explanation. We’ve seen these images so often that they’re instantly recognizable. We make specific associations with these images, which the cartoonist can manipulate to create the gag.

Cartoonists also frequently rely on settings that lend themselves to comic developments. Some settings are commonplace—a courtroom, a doctor’s office, or an elementary school, as examples—while other settings are removed from the everyday—a medieval castle or outer space. Other cartoonists choose settings in bars or bedrooms or boardrooms because, in their minds, that’s where funny things can happen.

One cliché setup has been a mainstay of the cartoon world for decades: the desert island. Why this setting has endured is a mystery. Do such tiny, precipitation-challenged islands litter the South Pacific? If so, why do castaways end up on them instead of, say, the shores of Tahiti? Despite all that, we frequently find two characters biding their time there, as isolated as Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot.

Sofia Warren executes the required desert island elements: an impossibly small island surrounded by ocean, barefoot castaways in tattered clothing, and the obligatory single palm tree. The drawing (below) tells half the story; the caption relies on the reader’s rapid understanding of the visual cliché setup to get the gag.

Given the sheer number of published variations on the desert island cartoon, it’s challenging to come up with a new angle. Nevertheless, more than a few undeterred cartoonists continue to rack their brains in search of a new iteration of this venerable theme. Joe Dator told us that when he came up with a desert cartoon that no one had thought of before, “that was a great day in my life as an artist.”

Other cartoonists avoid clichés as limiting or unoriginal. Indeed, they can be a crutch as much as a tool. Bob Mankoff observed that “they can get to be a little bit incestuous in that they just keep eating their own brain, running after their own tail, until it becomes a particular kind of game.” Mick Stevens has conflicting feelings about using these cartoon templates, such as the familiar evolving fish that ventures onto land:

I started trying to get away from the clichés on several occasions and they just sink back in. They just won’t go away, like I’m a slave to these things. I thought, “I’ll just use them ironically.” You can’t really tell the difference. The attempt might be ironic, but basically the reader doesn’t see the irony. I finally got to the point where I said, “I’m going to draw the last [evolving fish] cartoon.” I thought, “That’s it, I’m done.”

Below is the cartoon he’s referring to. It’s an example of a meta-cartoon, in which the cartoon itself references a cartoon convention.

“[The New Yorker] bought that cartoon,” he recalled, “which encouraged me to do more of them.” Thus, an ironic cartoon led to an ironic result.

We’ve mentioned a few common cartoon setups, but there are many more … so many more! We’ve included an appendix of the Top 100 cartoon clichés, and that list only scratches the surface, to use a cliché.

Top 100 cartoon clichés

Aliens encounter Earthlings

Ascent of Man evolution illustration

Astronomer in observatory

Beached whale

Big fish chasing little fish

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus

Bride and groom at altar

Building the Egyptian pyramids

Business executive pointing to sales chart

Car salesman and customer

Cat versus mouse

Cave paintings

Chalk outlines at crime scenes

Chicken versus egg

Clergyman delivering eulogy

Cloud-watching and identifying

Clowns in tiny car

Comedy and tragedy masks

Complaint window

Couple caught cheating in bed

Couples counselor with couple

Crash-test dummies

Crawling through desert

Creation of Frankenstein’s monster

Damsels in distress

Desert island

Dinosaurs and killer meteor

Discovery of fire

Doctor delivering bad news

Duelists

Dungeon prisoners

Easter Island heads

Emergency mid-flight announcement

Engraving on tombstone(s)

Explorers in quicksand

Fish evolving into land creature

Fortune-teller and customer

Funeral parlor viewing

Galley slaves

General pointing to service ribbons

Genie granting wishes

Godzilla destroying city

Good cop, bad cop

Guru on mountain

Guy in stocks

Halloween trick-or-treaters

Headless praying mantis

Hibernating bears

Ice hole fishing

Igloos

Invention of the wheel

IRS auditor and taxpayer

Jester trying to entertain king

Kids building sandcastles

Lab rat in maze

Last words on deathbed

Lawyer arguing to judge or jury

Lawyer reading will

Lemmings

Lost and Found window

Marriage proposal

Maternity ward

Men’s club codgers

Michelangelo’s God creating Adam

Military round table

Mobsters and victim at pier

Mount Rushmore variations

Munch’s The Scream

Noah’s ark

Optometrist and eye chart

Ostrich with head in sand

Parent reading bedtime story

Patent office

Patient on examining table

Patient on psychiatrist’s couch

Perusing books by genre in bookstore

Police lineup

Politician delivering stump speech

Prisoners counting the days with marks on wall

Realtor showing homes for sale

Road signs

Rodin’s The Thinker

Russian nesting dolls

Scientists with equations on blackboards

Selecting a greeting card

Snow globe variations

Star constellations

Stonehenge

Surgical team in operating theater

The damned in hell

The End-Is-Nigh Guy

The Last Supper

Traffic cop pulling over speeding motorist

Trojan horse

Tunnel of Love

TV news and weather

Viewing modern art in museum

Walking the plank

Witch stirring cauldron

Yoga class

You-are-here map

Excerpted with permission from Funny Stuff: How Great Cartoonists Make Great Cartoons (Prometheus Books). Copyright © 2024 by Phil Witte and Rex Hesner.