(Photography by Anne Ryan)

Jeff Deutsch has a plan to save the Seminary Co-op.

Imagine you’re in Hyde Park, walking west on 57th Street. At Kenwood Avenue, you pass Noodles Etc., apparently the true successor to the long-gone Agora after a string of North Side and Evanston interlopers—Prairie City Diner, Ann Sather, Lulu’s—came and went. Then it’s the Medici ingestible complex, Z&H Market Cafe, Cemitas Puebla, which has replaced Edwardo’s (in between there was a short-lived dumpling place), and Kinko’s, now FedEx Office. From the Hyde Park Bank, still right next door to Hair Design International (College students w/ID, $10 off haircuts, Tue–Sat) , you see your goal: 57th Street Books.

Even before you reach the little shingled portico, you anticipate taking the three steps down and pushing through the spring-loaded door. But tradition demands you first inspect the window displays. The last time you were here, it was a full window for a new children’s picture book about the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.

But you’re caught up short. Instead of books, there’s a sheet of paper taped inside the first window, screaming in all caps: STORE CLOSING. ALL BOOKS MUST GO.

Just as you’re overcome with the need to sprint the two blocks to the Seminary Co-op, you spy the sign in the other window: VISIT OUR WOODLAWN STORE FOR MORE CLOSEOUT BARGAINS.

Jeff Deutsch wants to be absolutely clear: “We would never do this,” he says in the very much alive and kicking Seminary Co-op, “but when things were as bad as they were, I said, ‘Let’s have a going out of business sale and see what happens.’ Because the fact is, it’s really that close.”

How close? In 2013, the year before Deutsch started as director, the stores—the Co-op, 57th Street Books, and, until November of that year, a Gold Coast outpost at the Newberry Library—lost $300,000. Deutsch knew this. When he was interviewing for the director’s position, he says, the Co-op’s board “was very candid with me about how bad things were financially.”

He also had two decades of bookselling experience under his belt, so he knew the landscape: the spread of the national book chains in the 1990s; best sellers available at Target and Wal-Mart (even a trip to Costco could net literary-minded bargain hunters a novel by Michael Chabon or Saul Bellow, EX’39 , along with their year’s supply of ketchup and mouthwash); and hovering above it all, Amazon, which debuted in 1995 as the “world’s largest bookseller” and spent 20 years chipping away at the very idea of any kind of brick-and-mortar retail by delivering more and more immediate gratification of more and more needs and fancies (before starting to open their own offline stores in 2015).

What Deutsch wasn’t ready for was the call he received less than three months into his Co-op tenure: the financial manager telling him they weren’t going to make payroll that week.

Deutsch “borrowed money and figured it out and everyone got paid,” but lost two nights’ sleep in the process. “It was actually a really good wake-up call,” he says—to the “tremendous responsibility” the Co-op has to its staff, customers, and neighborhood. He channeled that experience and the general “crisis mode” at the stores into a blunt but deeply thoughtful “call to action” issued to the Co-op’s membership in May 2016: “While much has changed over the last five and a half decades, the commitment to an exceptionally curated inventory, and to our remarkable community, has not. … We have a six-figure annual operating deficit and are working tirelessly to bridge that gap without compromising the character of the store.”

That remarkable community started out in 1961 with 17 students (and possibly professors—the historical record is inconclusive) kicking in 10 dollars each to form a cooperative to buy course books at wholesale prices. With wave after wave of new faculty members and students buying shares to get the 10 percent discount—now a 10 percent store credit toward furture purchases, assessed monthly—membership mushroomed and the store’s inventory branched out beyond course books.

The bent, nonetheless, remained resolutely scholarly. “You could find the University’s legendary professors there—the people who wrote the books that made it onto the celebrated Front Table,” former Law School faculty member Cass Sunstein wrote of his starstruck early days at UChicago, when you might need to squeeze past Wayne C. Booth, AM’47, PhD’50; William Julius Wilson; or Gary Becker, AM’53, PhD’55, to get at the book you were after. For less academic but equally curious and voracious readers—of all ages—the Co-op’s longtime general manager, Jack Cella, EX’73, opened 57th Street Books in 1983.

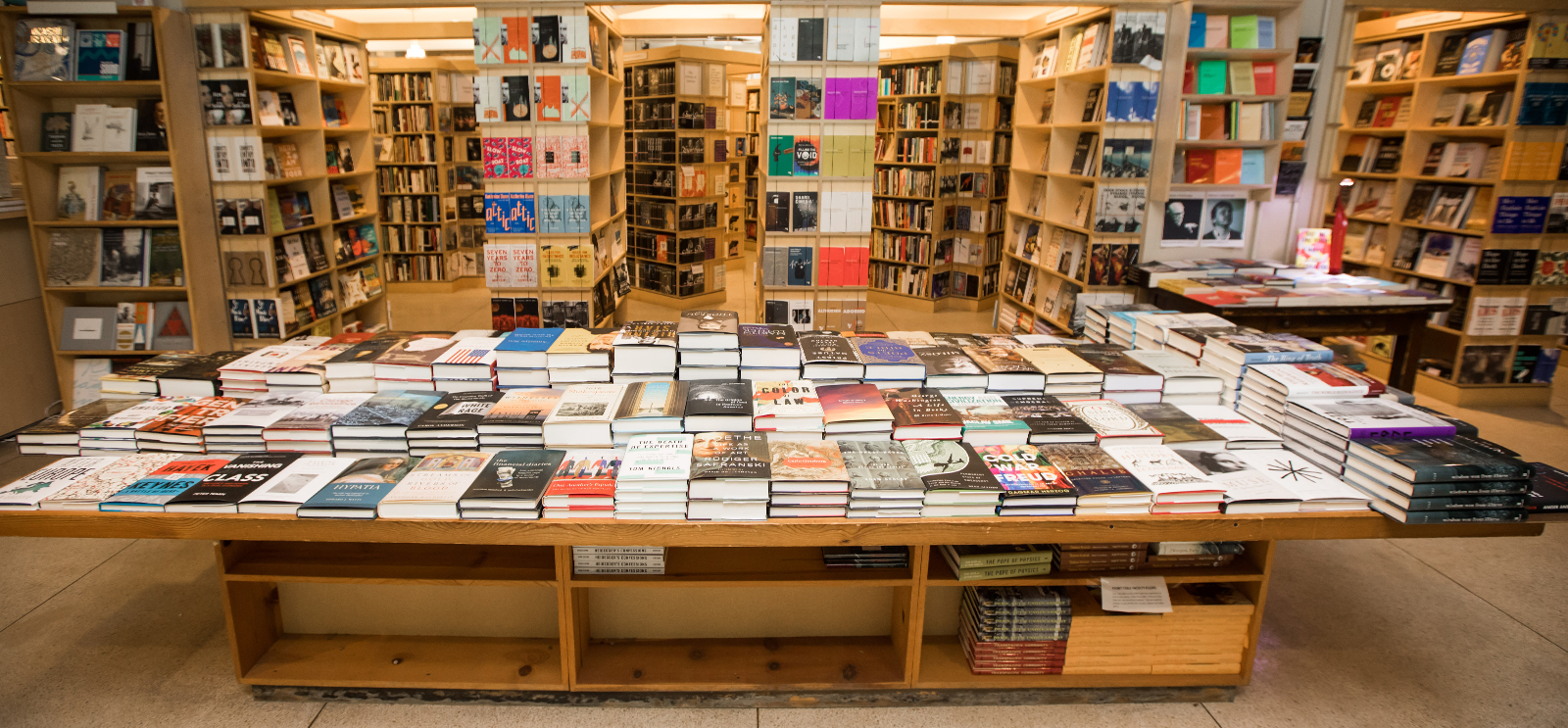

In 2012, as the Chicago Theological Seminary building was transformed into a new home for the Department of Economics and the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics—what is now Saieh Hall—the University helped the Co-op redesign and relocate to space in McGiffert House, just north of Robie House on Woodlawn Avenue. There, despite the daylight streaming through floor-to-ceiling glass walls (and better lighting at all hours), the Co-op’s labyrinthine atmosphere, encouraging exploration, lives on.

Browsing your way alphabetically through the literature section is sometimes as simple as turning a corner (C–D), or you might have to execute something like a knight’s move in chess—back out of an alcove and take two steps to the left—to make your way from Williams, John (Stoner, New York Review Books, 2006) to Williams, Joy (State of Grace, Doubleday, 1973, followed by the rest of her oeuvre).

You’re also bound to be distracted by the curated displays, little shadowboxes of books throughout the section. Where F meets G it’s Carlos Fuentes, Zsuzsanna Gahse (represented by Volatile Texts: Us Two, Dalkey Archive Press, 2016), and a David Gates story collection. In S, it’s new paperbacks of Georges Simenon’s Inspector Maigret novels. Jump over to European history, which takes up one long wall, and you can feel the tug of classical studies at your back. Is it finally time to tackle Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? All six volumes are here in both Penguin (1995, paperback) and Everyman’s Library (2010, hardcover) editions.

Before you get carried away, however, you remember that you’ve been stalled out at the Battle of Fredericksburg in volume two of Shelby Foote’s The Civil War (Vintage Books, 1986) for more than a decade. That’s when you spot, facing out among all the spines, the cover of a Johns Hopkins University Press edition of The Iliad (2012, Edward McCrorie, trans.). Instead of the standard Grecian urn treatment, it’s a photograph of Muhammad Ali raging over a supine Sonny Liston at the end of their second title fight. Epic.

An average bookstore, Deutsch says, stocks anywhere from 10,000 to 20,000 titles. The Co-op has approximately 100,000 titles on its shelves. The more important number that distinguishes it from other stores, according to Deutsch, is how often some of those titles sell. To be reliably profitable, bookstores must move books out of stock quickly. The Co-op is committed to stocking books that hang around. “Some we sell just once a month, once a quarter, once a year, or once every other year,” he says. He can also point to books that only sell after three, six, even 17 years on the shelves—and in most cases that book is reordered and put back out to wait for the next reader who may not even know they’ve been searching for it all their life.

“What makes the Co-op so great is that it is so unabashedly invested in the necessity of books,” author (and Co-op member) Aleksandar Hemon wrote to Deutsch last year. “You can read that investment in the depth of reading choices, in the width of human interests the books cover, in the thoroughness of making sure no corner of the human mind is underrepresented”—all of it, Hemon notes, “available with a 10 percent credit for members.”

To say that Deutsch is a book lover who grew up in a book-loving family is an understatement worthy of Ernest Hemingway. His mother worked for Simon & Schuster. His father loved going to bookstores and took the young Jeff on his frequent rounds. His sister Erica Deutsch, AB’95, studied philosophy in the College. But, Deutsch says, when it came to “serious books,” his grandfather was the biggest influence. A suit salesman in the ultra-Orthodox community of Brooklyn’s Borough Park neighborhood, he studied and discussed the Talmud with the same group of men—what’s known as a chavrusa—for 40 years. “I would go with him sometimes,” Deutsch says, “and I’d be this little kid sitting at the table looking at all these big men and realize that, really, friends coming together over books was a critical thing.”

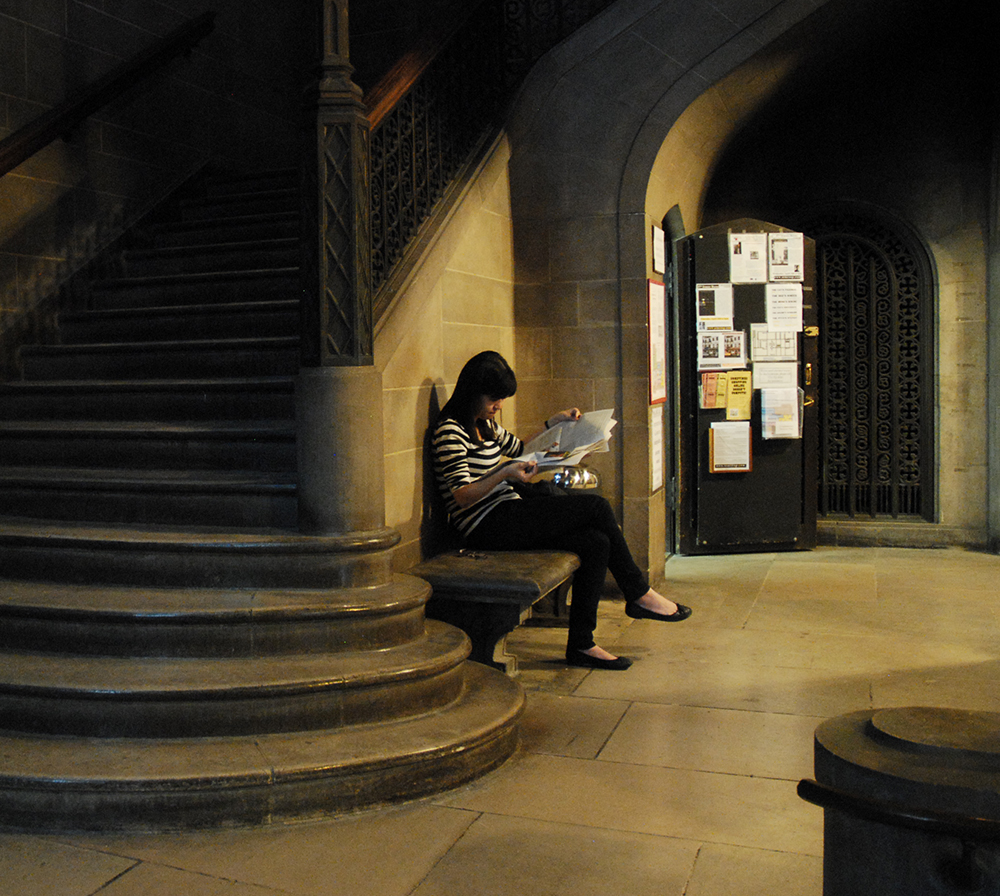

Like the honorary UChicagoan he’s quickly become, Deutsch still remembers his first visit, as a teenager, to the “old” Co-op. “As soon as I descended that staircase, that was my oasis,” he says. “I found a place I could go for refuge.” Deutsch says he “got into bookselling not to sell commercial fiction, not to sell health books, diet books, but really to sell serious books,” adding, “The impression that Jack and the Co-op made on me as a young man stayed with me, and I tried to replicate that through every store I’ve worked in.”

That has included a stint at a Seattle Barnes & Noble—in the exact spot, Deutsch notes, where Amazon’s first brick-and-mortar store now sits—and as director of the student bookstores at the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford. Deutsch “couldn’t have been happier” at Stanford, he says. “Loved the community. Loved my boss. Loved the campus. … Pretty much felt like it was the job I was going to retire from.” But barely a year into his Palo Alto tenure, word went out that Cella was stepping down as general manager of the Co-op after 43 years.

“I knew I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night if I at least didn’t throw my hat in the ring,” Deutsch says. “I know that job’s not going to open up again in my lifetime.”

The Co-op’s board recognized a kindred spirit, and in July 2014 Deutsch moved into the director’s chair. Now, instead of trying to bring other stores up to the level of the Co-op, he was responsible for making sure the Seminary Co-op remained what he had always seen it as: “a bookstore like no other.”

It starts with the inventory, of course, but you also need the right guides. When it comes to hiring booksellers, Deutsch looks for “bookish but also engaging” people who “listen as much as they talk and are curious to learn about what others are reading.” And they should have passion.

Case in point: on the first day of the Co-op’s most recent member sale, 57th Street Books manager Kevin Elliott was talking Russian novels with a woman who had stopped into the store at lunchtime. He recommended Mikhail Shishkin’s Maidenhair (Open Letter, 2012), which then reminded him of Andrés Neuman’s The Things We Don’t Do (Open Letter, 2015), a story collection translated from the Spanish. “It’s a gateway drug to short stories,” Elliott said, pulling a copy from the shelf for her. After spending a few minutes with each, she went with the Shishkin.

This is also a community—of booksellers and customers—that’s not afraid to judge a book by its cover. Someone buying a paperback copy of George Saunders’s short story collection Tenth of December (Random House, 2014) was enough to spur an impromptu poll in 57th Street’s first room: which cover did people like best? Hardback or paper, black or blue? The general opinion was that black better reflected the themes of the book, but it sure was a pretty blue.

Deutsch has gone on record: “We are resolute in growing, not cutting, our way out of the deficit.”

Since starting as director, he has recruited children’s author Franny Billingsley, LAB’71, who worked at 57th Street Books in the 1980s, to manage the store’s children’s section—and enlarge it by 30 percent. (They also got rid of a 30-year-old carpet there.) He promoted bookseller Alex Houston (pronounced like the Manhattan street, not the Texas city) to marketing director, charged with heading up a team to integrate events more and more into the Co-op’s daily rhythm. In 2016, the bookstores hosted or cosponsored more than 391 readings, book signings, discussions, and family events, like last September’s celebration of Roald Dahl’s centenary. They’re on target to top that in 2017. This has meant strengthening partnerships with departments and centers across the University, from UChicago Urban to the Center for East European and Russian/Eurasian Studies.

Just as important, the Co-op has begun working more closely with other South Side institutions. As one example, when author Zadie Smith came to Chicago last fall, Houston and her team arranged for Smith to appear with writer Vu Tran, assistant professor of practice in the arts at UChicago, in a sold-out event at the nearby DuSable Museum of African American History.

Deutsch says there’s a “revenue-driving aspect” to some events—when former president Jimmy Carter visited in 2015, they sold 600 books in two hours—but most of the time they’re lucky to break even. Really, he says, it’s about “the cultural good; it’s certainly about contributing to the conversation.” For those who miss the conversation, many events are now available via the Co-op’s new podcast, Open Stacks. Another popular feature among the “diaspora” (the staff’s name for alumni and faculty who have left Chicago) is the Co-op website’s virtual front table, which updates in real time. Now, says Houston, “people can sit in Switzerland or China and see exactly what’s on the front table.”

There is, potentially, another big change on the horizon—the kind that won’t necessarily affect anyone’s experience of the Co-op or 57th Street Books but that will help the stores in the long run: nonprofit status.

“The argument I want to make and win with the IRS, presuming our shareholders support this,” Deutsch says, “is that bookselling is a cultural pursuit in and of itself and should be acknowledged as such.” He compares it to theaters and publishers: some are in it to turn a profit, others are mission driven. “That’s how I see our bookstores: as mission-driven cultural institutions that are pursuing a cultural value that is nonquantifiable in just economic terms.”

Providing the browsing experience that Co-op customers depend on—the ability to find almost any book, pull it off the the shelf, examine it closely, and decide if it’s something they want to own—means having books on the shelves that don’t necessarily sell very often. It’s all about “making the statement that we’re not in this for the money,” Deutsch says.

Bookstore as nonprofit is not an unheard-of model. Housing Works Bookstore Cafe in New York City supports HIV/AIDS and housing services. Closer to home, Open Books in Chicago’s West Loop is organized around its literacy programs. But Deutsch knows of no other bookstore whose cause and mission is bookselling. “There are quite a few bookstores that are acknowledging that they’re cultural institutions,” he says. “So we’re not the only ones that feel this way.” He thinks that if the Co-op can create the right model—using nonprofit status to help finance at least part of the store’s basic operations—other bookstores might be able to pursue it too.

Before Deutsch and the Co-op’s board can approach the IRS, however, they need the approval of a majority of their shareholders. When you have 60,000 shareholders—and valid email addresses for just 15 percent of them—getting that approval is almost impossible. So the Co-op has spent the past year openly communicating plans to “regroup” shareholders into “charter members” and “active shareholders.” Both groups still get the 10 percent credit for purchases, but only shareholders will have a vote on store matters. (Customers who have never been shareholders can become members and receive the credit; visit semcoop.com/join-co-op for details.)

As of May 1, those shareholders who hadn’t made a purchase in more than two years or didn’t signal their wish to participate in governance automatically became charter members, and Deutsch says he also heard from “a bunch of people” who had bought books but weren’t interested in voting. As he recalls one loyal member telling him, “You guys take care of the governance. I don’t need to be involved. As long as the books are on the shelves, I’m good.” The end result, he says, is that the rolls went from more than 60,000 shareholders to 9,000 —a much nimbler structure to help the stores chart their future.

Last April Publishers Weekly named Wild Rumpus, in Minneapolis, its Bookstore of the Year. Wild Rumpus proclaims its difference from its front door, nested within which is a child-sized door on its own hinges. Inside, the store’s design slowly transitions from shabby chic to verdant forest, in homage to Anne Mazer’s book The Salamander Room (Dragonfly Books, 1994). Here you won’t find just a bookstore cat (several, actually); there’s a chinchilla, a pair of doves, a ferret, a chicken, rats, and a tarantula. The selection of children’s books is so comprehensive—every book you remember (or forgot about until just now) and countless contenders for the Harry Potter and Lemony Snicket crowns—you almost feel sorry for the smart phones all these children were tethered to only minutes ago.

Oren Teicher, CEO of the American Booksellers Association, says succeeding is now about “creating an experience more than selling a commodity.” In today’s “fiercely competitive environment,” that goes for every brick-and-mortar retailer, not just bookstores.

Deutsch isn’t about to start leaning on wildlife, even if the front door at 57th Street Books now proclaims “dogs welcome! (encouraged, really).” What he has is what the Co-op has always stood for: in his words, “a place … where the most seasoned of readers can once again feel a sense of wonder in discovering a book; where our communities can come together over a shared recognition of the insight and fulfillment that knowledge, ideas, and literature provide.”

What Deutsch is doing—in his pursuit of nonprofit status, in the growing activity in the stores and online, and in his calls to action (he wrote a second this past May)—is reminding the Co-op community and the broader world that bookstores like the ones he runs are worthy of their support.

The message seems to be working. The month after Deutsch’s May 2016 call to action, the Co-op’s sales were up 28 percent over June 2015, helping the stores achieve their first year of growth “since the turn of the century” and allowing them to reduce the deficit to $200,000. As of this past May, the Co-op’s 2017 sales showed a 10 percent gain over 2016.

The numbers are trending in the right direction, but the stores are still losing money. “The business is incredibly difficult,” Deutsch says. “We have to fight every day to earn our keep.” His friends and family used to question the wisdom of bookselling as a career, he says; now they wonder if he shouldn’t get out of brick and mortar altogether and get into some other form of content delivery. He counters that they don’t “understand what the calling is. It’s about handling physical books and helping readers discover them.”

Deutsch says he and his team recognize that they’re running a business that is “not a smart business, because we don’t believe it’s just a business. We believe it has cultural value, extra-economic value, that cannot be found on a profit-and-loss statement.” Therefore, he concludes, “Inefficiency has its place. In raising children, in most artistic endeavors, and in bookselling, a modicum of inefficiency is in order.”

What moves at the Sem Co-op?

Jeff Deutsch shared the store’s best sellers of 2016. (The Fiction and Poetry and Nonfiction lists exclude course books and books featured at store events.)

Fiction and Poetry

- My Brilliant Friend, Neapolitan Novels Book One, by Elena Ferrante

- The Sympathizer: A Novel by Viet Thanh Nguyen

- Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

- The Sellout: A Novel by Paul Beatty

- The Story of a New Name, Neapolitan Novels Book Two, by Elena Ferrante

- The Story of the Lost Child, Neapolitan Novels Book Four, by Elena Ferrante

- Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Neapolitan Novels Book Three, by Elena Ferrante

- A Little Life: A Novel by Hanya Yanagihara

- Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore: A Novel by Robin Sloan

- The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Nonfiction

- The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation by Natalie Y. Moore

- The University of Chicago: A History by John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75

- Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond

- The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

- The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander

- At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell

- Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and a Culture in Crisis by J. D. Vance

- The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America by Ethan Michaeli, AB’89

- Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit

Course Books

- The Marx-Engels Reader, Second Edition, by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; edited by Robert C. Tucker

- The Second Treatise on Civil Government by John Locke

- Leviathan; or, The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil by Thomas Hobbes

- The Two Discourses and the Social Contract by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

- The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

- Reflections on the Revolution in France by Edmund Burke

- Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo by Plato

- Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud