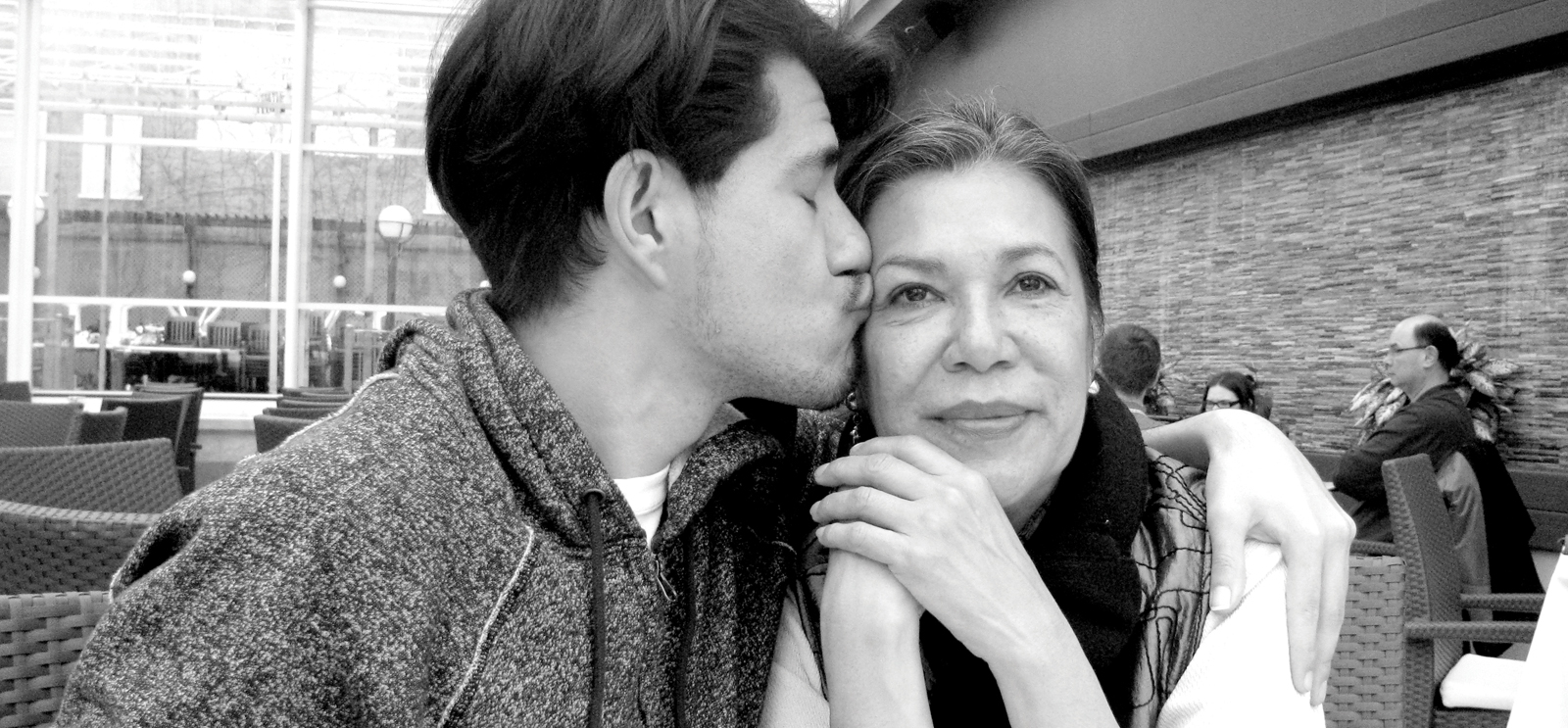

Castillo and her son Marcelo, or Mi’jo, in Chicago in 2013. (Photo courtesy Ana Castillo)

A mother remembers the cusp of her son’s adulthood.

This month the Feminist Press published Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me, an essay collection by Ana Castillo, AM’79. Written over 20 years, the essays focus on her experiences as an American woman of Mexican descent, as a writer, and as a daughter and mother. They culminate in Castillo’s searching, emotional account of her son Marcelo’s two-year incarceration for “a senseless robbery” in 2009, the social and personal forces that led to his troubled act, and his reemergence, in prison, as the son she had known. Ten years before the robbery, she sketched her life with Mi’jo, as she affectionately calls Marcelo, on the cusp of his adulthood. For an interview with Castillo, see “Radical Curiosity.”

Whenever Mi’jo wants to come into my bedroom he knocks, of course. It’s something he learned how to do at five. But in the last couple of years, before he enters he gives me an Eastern-style bow and says something in Japanese, I think, which I don’t understand. I don’t even know where he learned it. Maybe TV. You think all your child is picking up from television is how to become a cold-blooded killer and then he comes up with an elegant ritual of respect toward his mother.

I am thinking about this because my only child is now 15 and he is beginning to separate. At the brink of adolescence I heard the first tear at the seam, but he was still a clumsy duckling returning every day to the fold of his mother’s wing. Now he is nearly six feet tall and will start shaving soon.

He’s kind of got a girlfriend.

He comes into my room, his single mom’s room, usually accompanied by his little dog, Rick. The dog is less certain that it is welcomed into this forbidden domain than his master and hesitates when Mi’jo is invited in. I am usually not in the middle of anything that can’t be interrupted, my laptop propped on a pillow or frayed tarot cards out for a little nightly musing or I’m reading or doing all three and listening to a jazz program on Chicago National Public Radio. I am always “decent,” which is how a woman who sleeps alone usually dresses for bed. No gratuitous nudity on my own account.

Before you know it my almost grown-up boy is sneaking under my comforter and trying to get the dog to hop in too. (Which it does not do, being that the dog is no fool and understands the hierarchy of command in our household: do not—if you know what’s good for you—jump on the mama-san’s bed.)

We have our little chats then, my almost grown-up son and I, about his grades at school, homework, what money he needs now and for what, or about where each of us is at in our lives on that given day. “Are you in a relationship?” I ask him.

I say that word because I’ve overheard him use it on the telephone with his best friend. I’m trying to imagine what “relationship” could mean to a pair of 15-year-olds.

“I don’t know,” he says. I guess he’s trying to understand what it means to him, too.

“You’re too young,” I say, predictably to him as the strictest mother he knows. “You’re like a green corn. You’re not ready to give anything. Too green.”

“And you’re too old for a relationship,” he says, also predictably as a teenager who has to get in the last word. It doesn’t have to make any sense as long as it’s the last word.

Well, I’m not in any “relationship” so it’s a moot point at the moment, but I must admit he’s got me there. I’m pretty content dancing solo and, like a bona fide bachelor, getting very accustomed to my habits. (I’d say “bachelorette” but it would call to mind The Dating Game show and that’s some- thing I really don’t do anymore, not to mention the fact that I can recall that program very likely makes Mi’jo’s point.) Maybe my wise 15-year-old is right, perhaps I have gotten too old for a relationship. If he’s too green, possibly you could also get so ripe you need to stand all on your own to be fully appreciated by everyone, no compromises, no fifty-fifty sharing. Most importantly, no shared bathroom. (There are two basins in my bathroom but one is used for a flowerpot.)

But what I say to my son is this: “Go to bed. I pay the bills around here. I can do whatever I want.”

“I’m the man of the house,” he says. I can’t believe my ears. Before I have a chance to react, he adds with a teasing smile, “I’m the man of the house because I’m the only man in the house.”

“I am the woman of the house,” I say.

“And Rick is the dog of the house,” he says with a full-fledged grin and puts his head on my shoulder. Suddenly he’s not 15 and ready to soar off into new horizons to escape the nagging, oppressive ball and chain previously known as Mami, but a peaceful, trusting child who (like his mother, and yes, even like the dog, and every other living thing on the planet) is just trying to figure out where he fits to keep everything balanced—and in harmony.

“Goodnight,” I say to my son with a kiss on his forehead, now covered with an outbreak of teen acne.

He gets up; the dog scampers out quickly behind him. Mi’jo, at the door, turns around, bows, and bids goodnight with his Japanese phrase. I wish I knew what he is saying. But I’ve never asked him. It’s one of the many new things about him now that are him and that I’m not expected to understand, just let be.

Ana Castillo, AM’79, is the author of So Far From God (1993) and Sapogonia (1990), both New York Times Notable Books of the Year, as well as The Guardians (2007), Peel My Love Like an Onion (1999), and many other books. She is returning to her hometown, Chicago, after 12 years in the Chihuahuan Desert of New Mexico. Reprinted from Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me by permission of the Feminist Press. This essay was originally published in Salon.