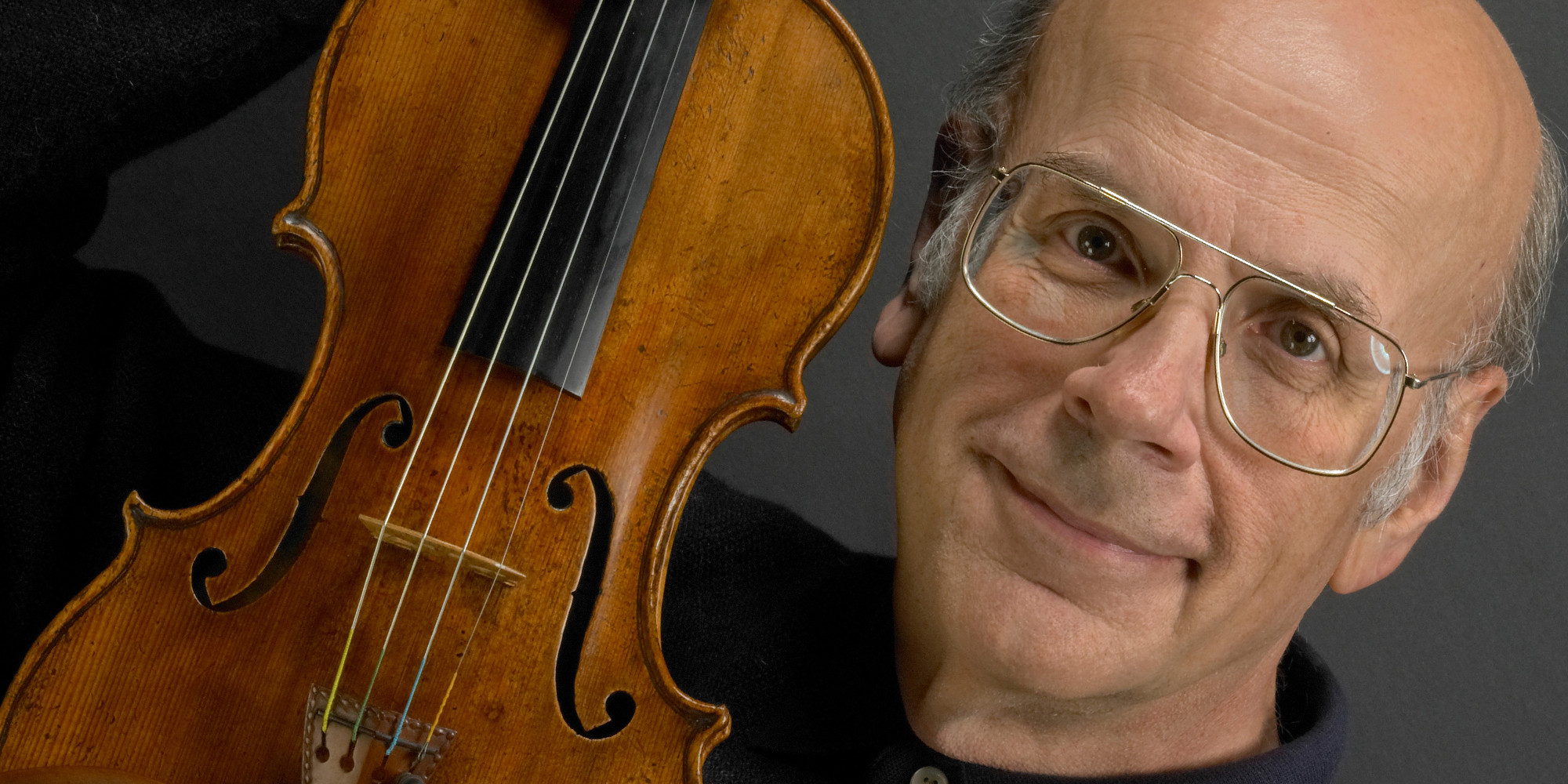

David Fulton, SB’64, with the 1742 “Lord Wilton” violin by Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù.(All photos courtesy David Fulton, SB’64, except as noted)

David Fulton, SB’64, has owned some of history’s most treasured violins, violas, and cellos. Now he’s telling their stories—and his own.

When a 15-year-old David Fulton arrived at the University of Chicago, his ambitions were clear. “I was going to be a great mathematician,” he says. It didn’t take long for that dream to end: “I found out very soon I was not going to be a great mathematician, and I’d be lucky to get through the program—which I did.”

Amid that trying process, Fulton, SB’64, who’d been playing violin since the fourth grade, found refuge in the University Symphony Orchestra. He spent nearly three years as concertmaster—the first chair violinist, who tunes the orchestra and sits in a place of honor next to the conductor. The position brought with it two perks: a $100 quarterly stipend and access to an 18th-century violin made by the Italian luthier Carlo Antonio Testore. It was, Fulton writes in his book The Fulton Collection: A Guided Tour (Peter Biddulph, 2021), “the first really fine instrument I had ever had in my hands.”

It would not be the last. Alongside his career as a computer science professor and database software company founder, Fulton spent two decades amassing what was regarded by many as the world’s greatest collection of stringed instruments. In total he has owned 18 violins, six violas, and four cellos by makers including Antonio Stradivari; Andrea Guarneri; Guarneri’s grandson Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri, known as del Gesù; and Giovanni Battista Guadagnini. These 17th- and 18th-century Italians are regarded as history’s finest luthiers, and their wares sell for millions, whether at auction or in private transactions facilitated by violin dealers.

Fulton’s collection had a dual purpose. He could lend out some of his instruments for concerts, competitions, and recordings, and he could protect the rest for the next generation. Of the roughly 600 Strads and 150 del Gesùs still in existence, Fulton believes the majority can and should be played—with care, of course. “They’ve been around the track,” he says, “but there are some that are kind of pristine, and those should be preserved so that you can see, in 100 years, why people admired Stradivari.”

Beginning in 2017, having owned nearly every instrument he ever aspired to, Fulton did something surprising: he sold all but four of them. “You certainly can’t take ’em with you, right?” he says of his decision to dismantle what he had so carefully built. By parting with the instruments now, he reasoned, he could use the proceeds to support his philanthropy.

As he gathered instruments, he gathered stories too—of luthiers and dealers, musicians past and present, fellow collectors. Those have remained with him, even though the instruments haven’t, and form the backbone of The Fulton Collection, a memoir of what he describes as his “ecstatic madness.” Alongside photographs and historical information about the violins, violas, and cellos he owned, the book includes Fulton’s lively reflections on how he acquired them, why he loves them, and how they sound. He presents the instruments not in chronological order but rather in the order he purchased them.

Fulton suspects his collection may turn out to be one of the last of its kind. The monetary value of 17th- and 18th-century Italian violins increased sharply beginning in the 1980s; many have also been entrusted to governments and cultural institutions, taking them off the market. His book is a tribute to the confluence of circumstances that allowed him to be the guardian of so many important instruments at one time.

But, he says, one never knows when a new golden era for violins will dawn. Stradivarii were not universally admired in their own time; their true potential wasn’t recognized until a few decades later, after concert halls got bigger—a shift that better suited their rich sound. Violin experts estimate that it can take anywhere from 80 to 100 years for an instrument’s tone to stabilize. “Point being,” Fulton says, “you don’t know what modern instruments … are going to be as revered as Stradivarii.” And when they are, some lucky collector will be waiting.

String stories

“Marsick” violin Antonio Stradivari, 1715

In the late 1990s, up-and-coming violinist James Ehnes had a problem. He had been playing various loaned violins, and he knew his career could not advance without access to a top-flight instrument. He found a beautiful violin for sale, a 1715 Strad named for its onetime owner, the 19th-century Belgian violinist and composer Martin Pierre Joseph Marsick (1847–1924).

Ehnes thought he’d found sponsors who could buy it for his use—a common ownership model in the classical music world—but the deal fell apart, and he feared the instrument would be snapped up by another buyer.

Fulton had known Ehnes since the violinist was a teenager and had watched his career with interest. Understanding the predicament, Fulton purchased the “Marsick” and gave it to Ehnes on an indefinite loan. It was the only time he bought an instrument for someone else; he knew Ehnes had a rare talent and wanted to help.

The “Marsick” transformed Ehnes’s career. “I can’t tell you how important that violin is to me,” he told the Seattle Times in 2004. “It allows me to do everything that I want to do, both in terms of technique and sound. There’s another aspect, too: People hear that I am playing a Golden Period Strad, and they think, ‘He must be pretty good.’”

After a roughly 11-year loan, Ehnes purchased the “Marsick” from Fulton. The two remain friends, and Fulton feels proud of the role he played in advancing an important artist’s career. “As you can tell,” he writes, “I am a total fan.”

“Lord Wilton” violin Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù, 1742

In his book Fulton describes the “Lord Wilton,” which he owned for almost 20 years, as “the Apollo of violins.” The instrument is named for its first documented owner, the fourth Earl of Wilton, Seymour John Grey “Sim” Egerton (1839–1898).

Lord Wilton was something of a celebrity in his time, as conductor and resident composer of the Wandering Minstrels, a group of aristocratic musicians who performed concerts to raise money for charity. As Fulton writes, it’s believed that the Gilbert and Sullivan song “A Wandering Minstrel I” from The Mikadois a nod to Lord Wilton and his compatriots.

Fulton purchased the “Lord Wilton” in 1999 for $6 million—at that time, the highest amount ever paid for a violin. Despite the beauty of its sound, Fulton eventually discovered a flaw in the instrument: a so-called worm track on its back. When wood-boring beetles attack a dead or dying tree, their larvae leave small tunnels that luthiers would patch with wood or another filler, leaving a small scar.

The worm track in the “Lord Wilton” was hinted at in an old paper record from a violin dealer and revealed conclusively in a 2019 CT scan, as Fulton was preparing to sell the instrument. (CT scans are increasingly a standard component of high-end violin sales.) This flaw reduced the ultimate sale price by $2 million—that’s an expensive beetle—but not Fulton’s affection for the instrument.

“Conte Vitale, ex Landau” viola Andrea Guarneri, 1676

For Fulton, the decision to expand his collection from violins to violas and cellos was a natural one. After all, he says, “you can’t play a string quartet with just violins.” The “Landau” viola—the third-oldest instrument Fulton has ever owned—is one of about five known Guarneri violas still in existence.

Although the instrument is officially attributed to Andrea Guarneri, some suspect it may be the work of his son (and del Gesù’s uncle) Pietro Guarneri of Mantua. Whoever made it, the instrument is exquisite; Fulton considers it the best-sounding viola he has ever heard.

While it’s often called the “Conte Vitale,” Fulton prefers to think of it as the “Landau,” a tribute to its later owner, the German Jewish lawyer and violinist Felix Landau (1855–1935). Fulton has purchased three instruments formerly owned by Landau, including a 1735 violin by Carlo Bergonzi and a 1743 del Gesù.

In the 1930s, Landau sent several of his instruments to England—ostensibly for repair, though in reality he hoped to prevent them from being confiscated by the Nazis. The instruments, including the viola, were saved, but Landau was not so fortunate. He died in what was reported to be a car accident in April 1935.

The “Landau” viola is now owned by the Dextra Musica Foundation, which lends instruments to gifted Norwegian musicians—a legacy made possible by Landau.

“Bass of Spain” cello Antonio Stradivari, 1713

Fulton is confident the “Bass of Spain” (cellos were sometimes referred to as basses in the 19th century) has the most colorful history of any piece in his collection. In the 1830s, the Spanish family who owned the instrument sent it out for repair. The luthier, with what Fulton describes as “overweening arrogance,” decided to remove the top and replace it with one he’d made.

Not long after, the original top was bought by a French violin maker. He, in turn, sold it to an Italian dealer who became intent on reuniting it with the cello—which he finally did, although the instrument was very nearly destroyed on a rough sea voyage soon after.

The cello’s strange life story did not end there. The “Bass of Spain” eventually found its way into the Singer sewing machine family, whose scandalous divorces and affairs made them newspaper fixtures during the 19th and early 20th centuries. (The last Singer to own the instrument, Paris Singer, had an affair and a child with the dancer Isadora Duncan, one of many boldface names with a connection to the “Bass of Spain.”)

But what is most extraordinary about the “Bass of Spain” is its sound. Professional cellists have described it as an instrument that offers “total freedom to express the widest possible range of emotions,” “the love of [my] life,” and “the voice of God … the greatest cello I’ve ever played.”