Home, home on the shtetl: Lecturer Sunny Yudkoff’s thesis in progress focuses on the work of tubercular Yiddish poets who lived at the Jewish Consumptives’ Relief Society in Denver in the early 1900s. (Photography by Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93)

Over one breakfast and two lunches. Es, es!

Ikh heyb uf mayn lid

in gezang tsu dir, Kolerade,

mayn Kolerade!

I lift my poem

in song to you, Colorado,

my Colorado!

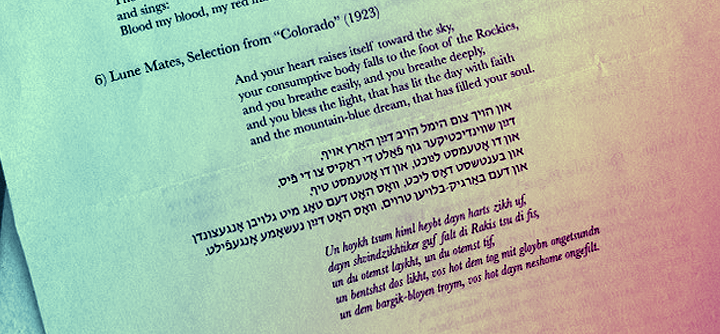

—Lune Mattes, from “Colorado” (1923)

I thought I understood what Yiddish was. But that was before I sat next to Sunny Yudkoff, Yiddish lecturer in the Germanic studies department and Harvard doctoral student, at a Divinity School Wednesday lunch.

Her thesis, Yudkoff told me when I asked, was on tubercular Yiddish writers who lived at the Jewish Consumptives’ Relief Society in Denver. I was astonished. When I think of my home state of Colorado, I think of cowboys and hot springs and narrow gauge railroads but definitely not Yiddish poetry.

So we kept chatting and eating, eating and chatting. Yudkoff invited Terren Wein, who organizes the Wednesday lunch, to her quarterly Yiddish tish (tish meaning “table”), where Yiddish students practice conversation over coffee and kosher bagels. And somehow I got roped in too. So here are five things I learned.

1. You cannot blag your way through a Yiddish tish using only rusty German.

I knew Yiddish was written in the Hebrew alphabet. I did not know the pronunciation, vocabulary, and spelling (when written in Latin characters) would be so utterly different from German. Luckily Yudkoff had supplied a cheat sheet, which included greetings and various ways to remark on the deliciousness of your bagel:

Hello Gut-morgn

(reply) Gut-yor

Goodbye Zay gezunt!

It tastes like the Garden of Eden! Es hot a tam vi gan-eydn!

It tastes like Leviathan with horseradish! Es hot a tam vi levyosn mit khreyn!

It’s finger-lickin’ good! Me ken lekn di finger!

2. Yiddish is not a dialect of German ...

... even though I had been taught as much in my German class many years ago. “A language is a dialect with an army and navy,” Yudkoff told me, quoting Yiddish scholar Max Weinreich (who originally made the remark in Yiddish: a shprakh iz a dialekt mit an armey un flot). The point is that the distinction between a language and a dialect owes more to political factors than anything else.

3. Yiddish is a “fusion language.”

It’s made up of three linguistic components: Germanic, Hebraic/Aramaic, and Slavic. English is also a fusion language. But unlike English speakers, Yudkoff explained, Yiddish speakers have an acute “component consciousness”—an intuitive understanding of which words are derived from which language—and can skew their word choice depending on the situation. Imagine, for example, if you were speaking English with a native French speaker, and you could easily choose only words of French derivation, so as to make communication easier. Wow.

The next week, Yudkoff was herself scheduled to give a Div School lunch lecture. So here are two more things I learned.

4. “Yiddish is not inherently funny.”

Of course this got a laugh from everyone in the room. “Yiddish is not and was never solely the domain of Woody Allen or Mel Brooks,” Yudkoff said. “It was a language that Communists wrote in, that soldiers fought in, that rabbis taught in ... that modernist poets experimented in, simply put, that people lived in.”

5. Yiddish is not endangered.

“It’s not a language of secular cultural production,” Yudkoff said. But Yiddish is the everyday language of ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities in New York, Jerusalem, London, and elsewhere. In linguistic terms, it’s considered post vernacular. I asked Yudkoff if she had visited the Jewish Consumptives’ Relief Society (which became a cancer hospital in the 1950s) when she was in Denver doing research. She drove past it, she said; it was behind a shopping mall.

I looked up the address and discovered that although I had never heard of the JCRS, I knew exactly where it was: on West Colfax, behind the modern-day novelty restaurant Casa Bonita. Where Yiddish consumptives once wrote poetry and spat blood, my kids and I had eaten sopapillas and watched the cliff divers.