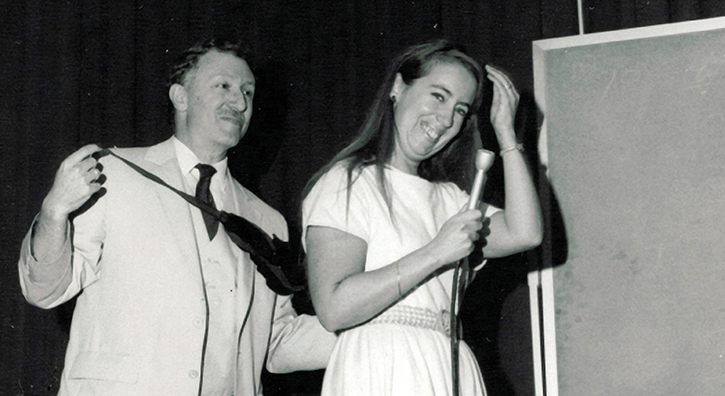

Simon blindfolds Ginny at the start of their performance at a mind readers’ convention, 1985. (Photo courtesy Simon and Virginia Aronson)

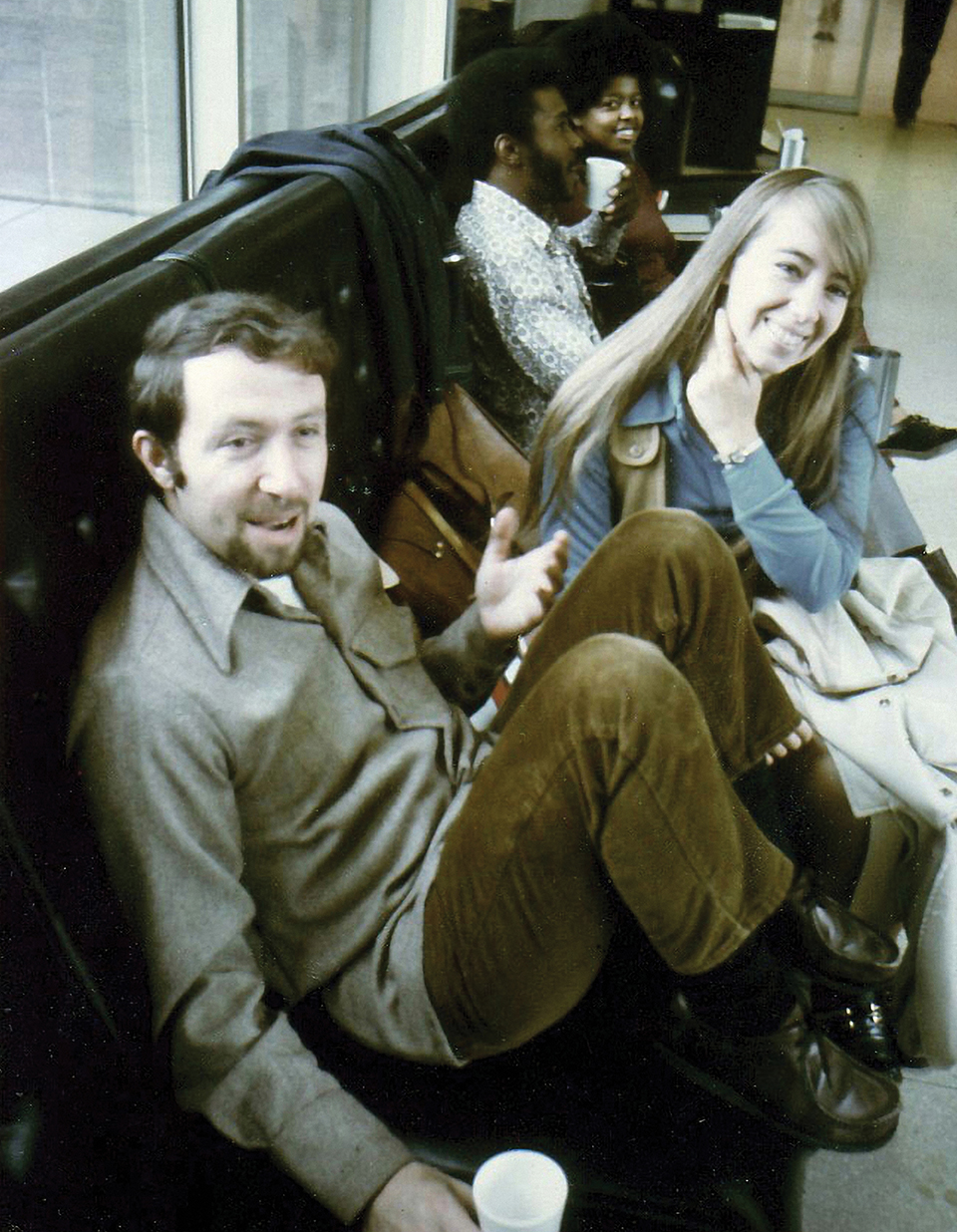

Simon and Virginia Aronson have been reading minds as a team for 40 years.

Virginia Aronson, AB’69, AM’73, JD’75, walks to a corner of the Lincoln Park condo she shares with her husband, Simon, AB’64, AM’65, JD’73. She turns her back to us, closes her eyes, and prepares to read my mind.

Simon, standing near me, starts an easy, well-rehearsed spiel. He takes a deck of cards, riffles through them, and says, “Stop when you see a card you like.” I stop him at the two of hearts. We turn to Ginny on the far side of the room.

“I think it’s a heart,” she says, “and I’m thinking it’s a low card, perhaps the two of hearts.”

Simon then bids me to select any two dice from a huge bowl of over a hundred different colored dice. I choose two at random.

“You’ve chosen a pink one and a purple one,” she says. Right again.

I roll the dice; Simon asks Ginny to tell us what the total was. “The total is 10, but it was too easy, because there’s a five on both.” So I roll again, this time a seven. Ginny tells me so, that it’s a five and a two, and which number is on which color die.

So far, all the props we’ve used belong to the Aronsons. For the next part, they ask me to pull something out of my pocket. I had come prepared with five small objects to test Ginny.

Simon points to the first object, a penny, and asks, “What’s this one?”

“A penny,” she says confidently, her back still to us.

Next I produce my membership card from the National Air and Space Museum. He has me hold it up. “Now concentrate on this,” he orders.

“It’s a membership card of some kind,” she says.

Simon holds up the next object, an SD memory card I bought for a tablet computer. Ginny ponders this for a few seconds, then says, “I’m thinking storage of some kind.” That’s good enough for us.

I produce a one-dollar bill, which she quickly identifies. Simon tells me to focus on the serial number and challenges his wife to read it off. She slowly recites it from the far side of the room: “Zero five four … six one seven … two one.” Right again.

Very impressive, but all of these objects are commonplace. Can Ginny handle something she’s almost certainly never seen before? My wild card, swiped from my musician wife, is a two-inch-high plastic bust of Ludwig van Beethoven. If anything will stump Ginny, I think as I reveal it, it’ll be this.

Simon doesn’t bat an eye as he instructs me to hold it up, then asks his wife what it is.

“I think I see some kind of figurine,” she says.

“But can you identify who it is?” he asks.

She hesitates for a few seconds, then says, “Is it … is it Beethoven?”

Now that’s magic.

Simon and Ginny have spent almost five decades performing their mind-reading magic act, dubbed “It’s the Thought That Counts.” Despite Ginny’s apparent clairvoyance, they acknowledge before every performance, “We’re not here to convince or persuade anyone. Our sole purpose is to entertain you.” Their act is one that only a handful of others around the world can do. In the trade, this kind of two-person mind reading is known as second sight. One of its earliest performers was 19th-century French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (after whom Harry Houdini named himself).

Simon Aronson first became fascinated by magic as a little boy growing up in New York and its suburbs. He hung around the local magic shop, taught himself card tricks, and even performed at other children’s birthday parties starting at age 11. But his introduction to mentalism (as magicians call the specialty field for apparent psychic magic) came from an unusual source: Broadway. “I saw a Broadway play called The Great Sebastians with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who were at the time one of the great acting husband and wife duos, about a vaudeville mind-reading act that got caught behind Nazi lines in World War II,” he recounts. The play opened with the actors venturing into the audience and performing a brief second sight act with the actual theater-goers. “It was apparently a funny play,” he says, “but I actually couldn’t tell you, because I only concentrated on the mind-reading act that they did, which was in the first two-and-a-half minutes.” Card magic remained Simon’s forte, but a seed was planted.

Magic wasn’t his only passion. Young Simon developed an interest in civil liberties (his father, Arnold Aronson, AM’43, was a lobbyist for civil rights and civil liberties legislation). He enrolled in the College with the plan of continuing directly to law school. He placed out of most of his first year, earning his degree in economics a year early. The Law School accepted him, but he wrangled a deferment so he could get a master’s degree in philosophy.

One deferment led to another, and he eventually started a doctorate. During this time he cotaught a class for first-years on humanities and social sciences with James Redfield, LAB’50, AB’54, PhD’61 (now the Edward Olson Distinguished Service Professor of Classical Languages and Literatures) in the New Collegiate Division.

At the same time, Simon continued experimenting with card tricks and seeking out other magicians. In 1965 he ran across a mind-reading duo at—of all places—a Woolworth’s in downtown Chicago. The magicians would entertain shoppers with a little mind reading, then sell them horoscopes. Simon befriended one half of the act, Eddie Fields; although Fields never taught Simon the secrets of his act, it inspired him to learn more. He resolved to create his own mind-reading act and started by reading everything he could on second sight. “In many ways, it was a very U of C kind of thing to do,” he confesses.

Simon had been frequenting a Chicago magic shop run by a well-known magician named Jay Marshall, who kept in his store a library of obscure works on the craft. Simon dug into Marshall’s collection with all the fervor of a grad student. “I spent weeks in his library researching all the manuscripts on two-person mind reading,” he recalls. “There must have been 30 or 40 different things, and from that, I put it all together to create something that would be workable for me.”

Once he and his first partner, his then girlfriend, had polished their act, they took it around Chicago, earning extra money for school by working at nightclubs and sweet sixteen parties. Along the way, he exchanged one girlfriend/mind-reading partner for another, then broke up with the second girlfriend—but kept her in the act. Meanwhile he started dating a sociology grad student named Virginia “Ginny” Cook.

Ginny was very much Simon’s opposite, hailing from Bremerton, Washington, and recruited to the University by the Small School Talent Search, which brought promising scholars from rural areas. She had no experience with magic and no interest in performing it. Whereas Simon enjoyed being the center of attention, performing for an audience terrified Ginny.

As time went on, though, Simon’s performances with his ex started to grate (“I kept assuring her, ‘Don’t worry, it’s only mental!’” Simon says). Ginny ultimately resolved to displace Simon’s magic partner. “Sitting alone on Friday, Saturday nights while he’s out with his beautiful ex-girlfriend was sufficient incentive,” she says. “Although I needed a lot of incentive to learn that because getting up in front of a public audience at that stage of my life, that was a big deal.” Simon agreed, and spent the next few months teaching Ginny the secrets of his act.

Magicians love to ruminate over the nature of magic, says Simon, and he’s no exception. He draws a parallel between magic and comedy. Just as a comedic punch line entertains with a sudden twist that upends the joke’s frame of reference, a magic trick entertains by seemingly breaking the rules of logic and laws of physics. A good trick creates “the illusion of impossibility,” he says. “Science sets forth the immutable laws of the physical world and the immutable laws of logic, and magic simply demonstrates that they’re wrong—or, at least, creates the illusion of it.”

The Aronsons guard the secrets of their act carefully. (I have my own theory, but out of respect for the Aronsons’ craft and the magician’s code, I leave solving the puzzle as an exercise to the reader.) But they will say two things about how their act doesn’t work. First, there are no hidden cameras, microphones, or electronics of any kind. Second, they’re not drawing on any paranormal abilities. Occasionally someone who’s seen them read minds will ask to engage them for their “psychic powers,” but Simon is quick to clarify that they’re entertainers only.

However the act works, it’s a big hit wherever they perform, whether for ordinary people (they’re popular at corporate events) or among other magicians at a convention. Acts like theirs are rare because the two mentalists must spend an enormous amount of time together to perfect it, and all their effort is lost if one partner moves on; hence, a married couple is particularly well suited. “Even magicians, who must be tired of seeing so much magic already, love to see two-person mind-reading acts perform,” Ginny says, “because it’s a rarity.”

Simon eventually abandoned his doctorate in philosophy to make his much-delayed entrance to the Law School; Ginny, who became dissatisfied with her work in sociology, followed two years later. At the time, both thought they would get their JDs and teach at the college level, using a combination of their degrees. But eventually, they found themselves attracted to practicing law instead.

When applying for jobs, Ginny added at the bottom of her résumé that she did mind reading. Consequently, “everyone wanted to know about mind reading,” she says. “They didn’t care what I had written for my law review article.” She received many offers and ended up joining the storied Chicago law firm Sidley Austin, practicing real estate law.

At the time, Sidley Austin had 140 lawyers, of whom “maybe there were five women, maybe six.” But her stage experience added to her confidence. “I’m controlling the room more or less when we’re doing mind reading, because everyone’s eyes are on me,” she says, “and that taught me a lot about how to run a negotiation.”

The couple would occasionally entertain colleagues and clients with magic. One client so badly wanted to learn Simon’s secrets he offered to fly them to Switzerland in exchange; another promised he’d send five new deals Ginny’s way. “Of course Simon never cooperates,” she says with mock irritation. (“I have my professional oath!” he retorts.)

Simon joined the firm Lord, Bissell & Brook and also became a specialist in real estate law. He found magic useful as well, albeit for a different reason. “If you have clients who are more than one-shot clients, they want to know you as a person,” he says. “They want to know, is this someone who’s interesting, who’s a neat person to be with, who can tell me more than what’s in the legal contract? So to be able to do card tricks, or have them over for dinner and show them a mind-reading act, or invite them to one of our shows, or do a show for their organization—that’s a way of cementing relationships.” (Also, he adds, “neither of us knows a thing about sports.”)

He also found a way to make his firm serve his magician ends by taking advantage of the typists. He made them a deal: he’d perform card tricks for them, and they’d type up the manuscripts of his books on card magic. Though as a performer Simon is best known for the mind-reading act with Ginny, many magicians know him better as an inventor of card tricks (he’s written nine books on the topic).

Simon eventually made partner, retiring in 1999. Ginny, the first woman managing partner at Sidley Austin, retired in 2010. With more free time, they regularly travel to magic conventions and host visiting magicians from around the world in their home.

The Aronsons have also worked to spread the joy of magic. They’ve endowed a scholarship at a children’s summer magic camp. They also funded a program at the UChicago Medicine’s Comer Children’s Hospital that brings a magician in once a month to boost the spirits of the kids receiving care there.

Simon has continued to develop his card tricks. For 52 years he has participated in a small weekly meeting of magicians who bounce ideas off each other—what magicians call sessioning. They’ll try out new tricks, hone their skills at others, get feedback, and sometimes share a professional secret.

But the Aronsons’ stock-in-trade is still “It’s the Thought That Counts,” which they’ve been able to perform more frequently since retiring. They refine the act constantly, based on the kinds of objects today’s audiences are likely to have.

As I leave their apartment, Ginny says to Simon, “You know, if we ever get a bust of Beethoven again, I think what I’d say is—” then cuts herself off and glances over at me. “But maybe we should wait until he’s gone.” Aw, nuts, I think—she read my mind.