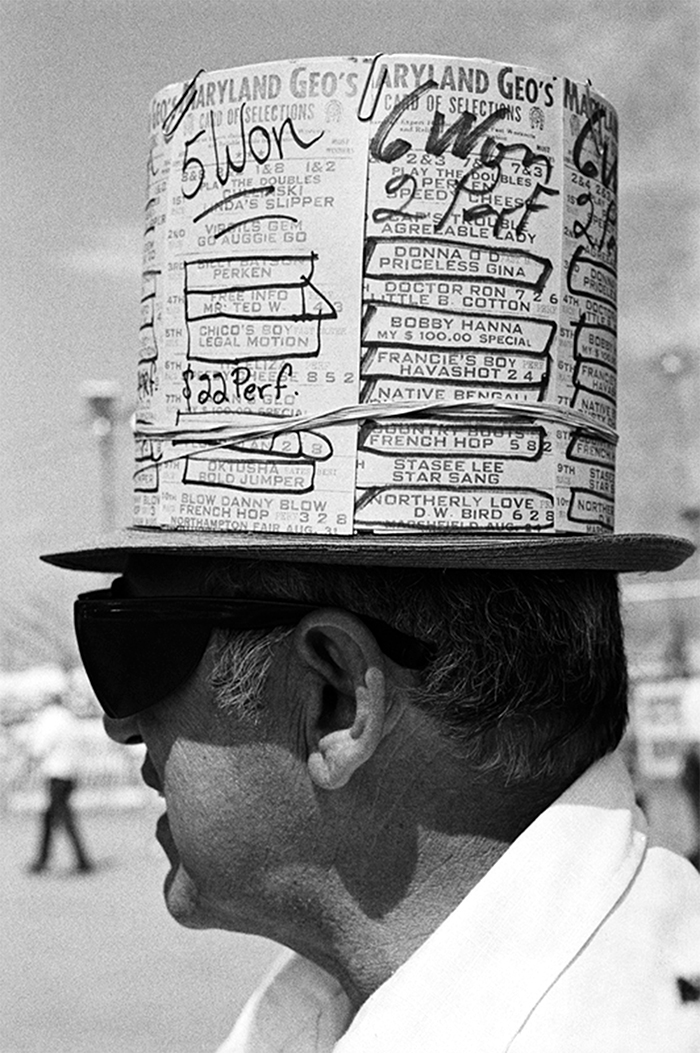

Crop of a photo by Henry Horenstein, EX’69. See the full photo below.

Henry Horenstein, EX’69, captured the end of a country music era.

Henry Horenstein, EX’69, is explaining why documentary photography is like studying history when he pauses. “Hmm, interesting,” he says. We’re talking by phone as he drives through Pennsylvania on a photographic road trip. An unusual house has caught his eye. He decides to double back. “This is the photographic process, right here,” he says.

Horenstein likes what he sees. “No kidding, I really have to,” he says. “Can you hold on one second?”

A few minutes later he returns, satisfied. “It’s actually pretty good,” he says. “A little Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”—Walker Evans’s famous book of Depression-era photography.

Horenstein, a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), believes in following his instincts. He’s spent his career heeding the advice of his RISD teacher Harry Callahan, who once asked Horenstein what he loved. “I said, ‘Music and horse racing,’ and he said, ‘Shoot those things. … Even if you get a bad picture, you’ll have a good time,’” Horenstein says. “I’ve kind of taken that for my goal in life.”

Callahan probably didn’t intend for Horenstein to take him so seriously (“I think he just said it as a blow-off line—he was trying to go out for a cigarette and a student was bugging him”), but the advice worked out. Horenstein is the author of more than 30 books, including several widely used photography textbooks.

He photographed plenty of musicians and horse races before moving on to wildlife, burlesque performers, and drag kings. “The subject really rules, in my opinion,” he says. “Some people don’t agree with that, but that’s how I look at it. And if you have a really great subject, things can be forgiven.”

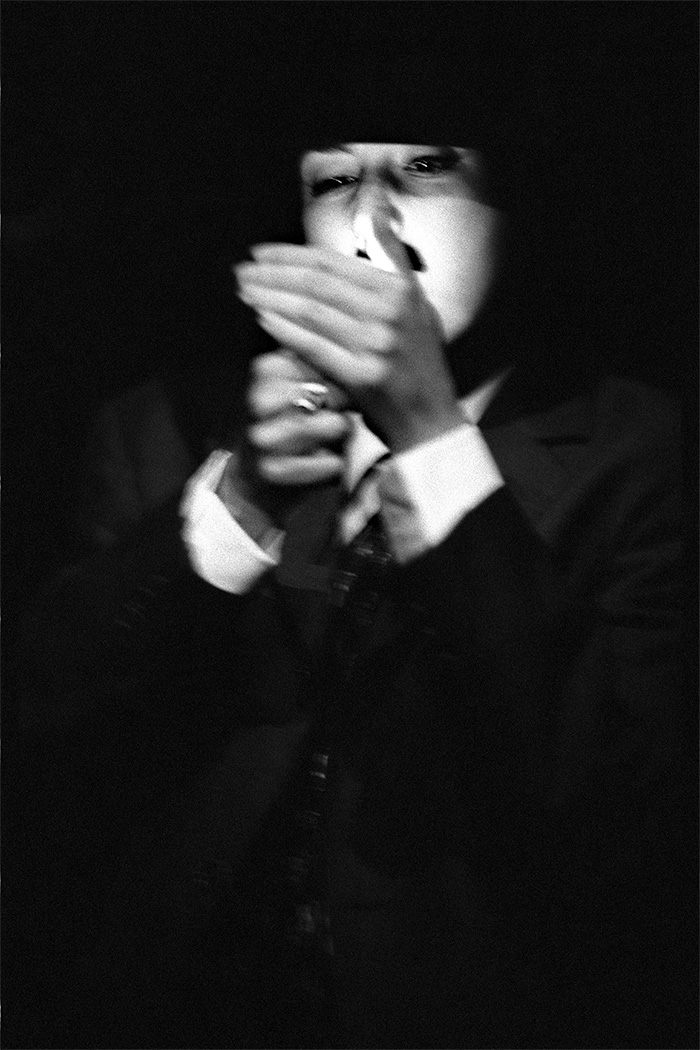

Take his 1980 portrait of Emmylou Harris. “It’s a good picture in a lot of ways, but it’s not that it’s a good picture that you remember it,” he argues. “It’s because it’s Emmylou Harris.” Still, Emmylou or no, the image grabs you: the singer’s gaze is fixed on something or someone unseen, her expression inscrutable.

His 2012 book Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music (W. W. Norton) includes that image of Harris alongside shots of Dolly Parton, Porter Wagoner, and Jerry Lee Lewis. But much of the collection, which was compiled over 40 years, is devoted to fans and honky tonks, backwater bars with jukeboxes and occasionally live music. These dives are disappearing, and Horenstein wanted to capture them before they were all gone.

Horenstein’s urge to document history goes back to his days at UChicago, where he took classes from Jesse Lemisch, then an assistant professor of history. Lemisch was part of a movement that advocated studying the history of ordinary people—“history from the bottom up,” as he described it. On Lemisch’s advice, Horenstein spent several months in England studying under E. P. Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class (Pantheon Books, 1963).

“He was writing about the workers during the Industrial Revolution, but he was singing my song,” Horenstein recalled in his memoir. Thompson’s work “offered me an entry into photography. I had no art background, but I did know a thing or two about history. Maybe I could be a historian with a camera.”

That plan got unexpected encouragement in 1969, when Horenstein was expelled for participating in a sit-in protesting the denial of tenure to Marlene Dixon, a leftist sociologist. He left Chicago and enrolled at RISD to begin his formal photographic training.

After art school, Horenstein took on a motley assortment of freelance assignments. He worked on and off for the Americana label Rounder Records, which played to his strengths. He also worked on a title called Drugs and You, Too, which didn’t. The book was intended to convince kids to steer clear of drugs, but “I doubt [my pictures] convinced anyone not to do anything except maybe never to become a photographer,” he jokes. In between he took photos for himself, gathering the images that would be included in collections such as Honky Tonk.

Today Horenstein’s work from the ’60s and ’70s looks rough and unfinished to him—“I didn’t know what I was doing”—but there’s a purity to it. He could take the same photos again today, and they’d be better, technically, but not so much from the heart.

His skills have improved with time, but his approach hasn’t changed; nearly 50 years after hearing the advice, Horenstein continues to shoot what he loves. “I like to be alone and I like driving. I like to see different parts of the country,” he says. So from time to time he leaves his home in Boston and takes trips like the one he’s on now.

“I’ve never really been through the Alleghenies,” he says. So far, at least, “it’s kind of boring for pictures.” But suddenly—again—his fortunes change. “I just saw another picture I want,” he says. He decides our call is bringing him good photographic luck. “Would you stay on the line for my whole trip?”