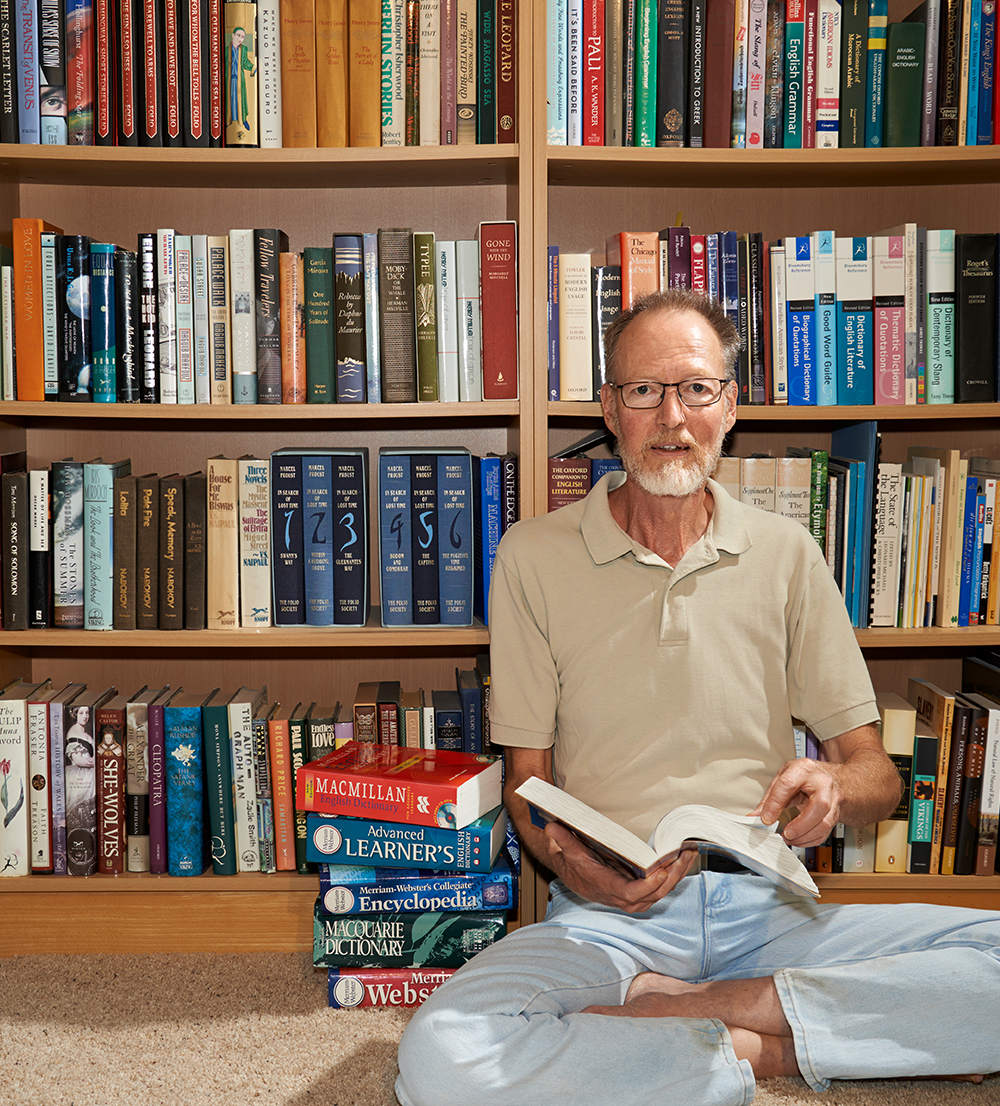

No writer can avoid clichés entirely, Hargraves writes in It’s Been Said Before, just as a cook doesn’t serve “completely novel and unfamiliar dishes at every meal.” (Photography by Stephen Collector)

(Noun, an author or editor of a dictionary)

When Orin Hargraves, AB’77, was growing up in Creede, Colorado (population 290), he spent a lot of time at his grandmother’s hotel. Instead of a high chair, the hotel had a giant dictionary. When it wasn’t in use as a makeshift booster seat, Hargraves liked to page through it.

Three decades later, he was living in London, working at a job he was tired of, when he spotted a newspaper ad placed by Longman, the dictionary publisher. Wanted: native speaker of American English with experience teaching English as a second language. As well as being American and legal to work in England, he had taught ESL in Morocco in the Peace Corps. At Longman “I got a week’s worth of training,” Hargraves says, “and that basically brought me into the world of lexicography. As soon as I started doing it, I realized that this was the thing I had been looking for my whole life.”

Since then, Hargraves has contributed to numerous dictionaries, including the New Oxford American Dictionary (2001, 2004, 2010), Macmillan English Dictionary (2002), and the Cambridge Dictionary of American Idioms (2003). He writes a monthly column, Language Lounge, for the website Visual Thesaurus.

Hargraves’s books include It’s Been Said Before: A Guide to the Use and Abuse of Clichés (Oxford University Press, 2014), Mighty Fine Words and Smashing Expressions: Making Sense of Transatlantic English (Oxford University Press, 2003), and travel guides to Morocco, London, and Chicago. A research consultant at the Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Colorado–Boulder, he has also deployed his linguistic knowledge as an expert witness and script editor. His comments below have been condensed and edited.

Small (adj., having comparatively little size or slight dimensions)

The world of English lexicography is very small. Probably no more than 100 people do it. We all belong to the same one or two professional societies, we go to the same conferences, and many of us work on the same projects.

A few lexicographers, an increasingly small number, do work full time for a particular publisher. Merriam-Webster still has an in-house staff of lexicographers, as does the Oxford English Dictionary. But most other dictionaries these days are written largely by freelancers like me. The pay is not great. Nobody gets rich being a lexicographer.

Prescriptivist (noun, one who advocates prescriptive principles, especially in grammar)

Among the lexicographers I know, we have all been dedicated word lovers from the time that we learned what words were. We all tend to think quite analytically. We all care how English is used, although I can’t think of any of us who are prescriptivists. The job of dictionaries is to document the way people use language, not to dictate to people how they should use language.

The background of people in lexicography is incredibly diverse. The majority, like myself, only have a BA. I know one guy who works on the OED who has a PhD in math.

Monotony (noun, tedious sameness)

You have to have a very high tolerance for monotony. Having a long list of words in front of you to define means there’s going to be a lot of repetitive work.

All lexicography today is very highly computer assisted. We have gigantic databases of language. For a given verb, we can see, what are the 10 nouns that are most frequently seen as the subject of this verb? What are the 10 or 20 or 100 nouns that are most frequently the object of this verb? If it’s a verb, is it used both transitively and intransitively? Is it also used sometimes as a phrasal verb? Like the word draw—you have draw up, draw in, draw out.

It means being completely submerged in a world of words all day long. And if you love words, well, you can’t beat it.

Sense (noun, a meaning conveyed or intended)

You will be able to define some words in five minutes, because it’s a complicated technical word or it has only one sense. Tendonitis, for example. Inflammation of a tendon. We’re done. Let’s move on to the next word. Another word may have half a dozen senses. Get or take has 50 or 70 or 100 senses.

The requirements of each dictionary are different too. The way you define a word for a learner’s dictionary, for someone who is just being introduced to English, is going to be much different than the way you would define it for a collegiate native speaker dictionary.

Cliché (noun, a trite phrase or expression)

I got to vent a lot of my annoyance with clichés in It’s Been Said Before. Let me say first of all that I am as great a user of clichés as anybody. In fact I actually heard myself earlier saying “at the end of the day,” which is a cliché I detest. Why do I use it if I hate it so much?

But really, everybody uses clichés. They’re a kind of gestalt wording, the first thing that comes to your mind. If you go to the cliché, as opposed to going to some more original way of saying something, you save yourself a lot of thinking time. Everyone understands it. That’s the big reason we use them.

Proud (adj., feeling or showing pride, much pleased)

I’m most proud of all of my commercially published books—three travel guides and five or six language reference books. I’m happy I even got to publish. I grew up in a town of 300 people. I hardly expected to even go to college.

As far as emotional attachment goes, I’d have to say the fiction that I’ve self-published on Amazon Kindle. I have one book that’s a collection of stories based on my experience of living in Morocco for three years. I wrote it—gosh, almost 30 years ago now. Can I be that old? Unfortunately I probably can.

I’m so glad that I wrote it when I did, because all of those experiences are not accessible to me now—the incredible richness and concentration of meaningful experiences that were packed into my years as a Peace Corps volunteer. I will probably go to my grave never getting a fan letter, but I still am happy I had that vehicle for publishing it.

Expert witness (noun, a witness in a court of law who is an expert on a particular subject)

The work that I’ve done is remarkably similar to lexicography: What does a particular word mean, or what do people understand when they read or hear this word? One case that I did was on what people understood by the term malware. It involved one company characterizing another company’s software, which was actually a kind of adware platform, as malware. It was very easy to see that, not surprisingly, people think of malware in a very negative way. So to call a piece of software malware is, without a doubt, a way of disparaging it.

Anachronism (noun, an error in chronology)

There’s a series that will be on PBS called F. S. Key: After the Song. Francis Scott Key, the writer of the national anthem, had an incredibly interesting and influential life.

I went over the scripts and corrected anachronisms—usages of words that weren’t correct because people didn’t start using the word or the phrase in that way for another 200 years or whatever. A number of them I recognized immediately, just because after 25 years of lexicography, you carry around a pretty good head knowledge. I have a sense of what’s modern and what’s really old in English.

If I came across something in the script and I thought, would a person in 1810 really say that? The great reference for that is the Oxford English Dictionary, because of its historical order of citations. Another great resource is the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary. You can see how a given word in one time period might have a certain set of synonyms, but 100 years later it has a different set of synonyms, because its meaning has evolved.