On campus in 1992, John G. Morris greets his hero, Robert Maynard Hutchins. (Photography by Tara Hoban)

Legendary photo editor John G. Morris, U-High’33, AB’37, reflects on his career in pictures.

In late February the celebrated photo editor John G. Morris, U-High’33, AB’37, flew from his adopted hometown of Paris to his birthplace of Chicago to appear at two screenings of Get the Picture, a 2012 documentary charting his career. After seven decades assigning, selecting, and publishing images of the deadliest world events, his antiwar sentiment is stronger than ever. His hope isn’t flagging either. “I can’t resist being an optimist,” he said after the first of the screenings, which opened the Chicago Irish Film Festival. “I don’t know why. The world is in terrible shape.”

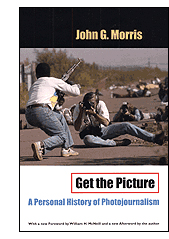

The film, directed by Dublin-based Cathy Pearson, borrows its name from Morris’s memoir, Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism (Random House, 1998, available in paperback from the University of Chicago Press). Pearson met Morris by chance in 2009, striking up a conversation with him in a Paris restaurant. The friendship that was sparked inspired her to make a movie that weighs 20th-century photojournalism’s impact on history by tracing one man’s enormously influential, if largely behind-the-scenes career. From the University of Chicago Morris goes on to cover California internment camps for Life, to send photographers like Robert Capa and W. Eugene Smith to the frontlines of World War II, and to become picture editor for the New York Times during the Vietnam War.

The film, directed by Dublin-based Cathy Pearson, borrows its name from Morris’s memoir, Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism (Random House, 1998, available in paperback from the University of Chicago Press). Pearson met Morris by chance in 2009, striking up a conversation with him in a Paris restaurant. The friendship that was sparked inspired her to make a movie that weighs 20th-century photojournalism’s impact on history by tracing one man’s enormously influential, if largely behind-the-scenes career. From the University of Chicago Morris goes on to cover California internment camps for Life, to send photographers like Robert Capa and W. Eugene Smith to the frontlines of World War II, and to become picture editor for the New York Times during the Vietnam War.

At the Times in 1967, Morris found a paper that “was totally dominated by word people.” He changed the newsroom culture and more, making photo decisions that helped shift public opinion on the war. Answering audience questions after a second screening later that weekend at the Logan Center, he recalled, “One doesn’t talk about political convictions when choosing pictures at the Times. But that was the underlying motivation. That’s why it was so important to me to get Eddie Adams’s picture at the top of page one.” The famous photo, Saigon Execution, captured the South Vietnam national police chief shooting a Viet Cong prisoner in the head. Appearing on February 2, 1968, it became an instant icon and a catalyst for the antiwar movement.

Taking such pictures is getting harder. In the film, CNN’s Christiane Amanpour and others emphasize the growing danger faced by journalists covering war and unrest. “Photojournalists seek the truth,” Morris said. But more and more, they find themselves targeted, with 1,054 journalists killed since 1992 and 703 of those murdered, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Born and raised on Woodlawn Avenue in Hyde Park, Morris attended the Laboratory Schools and was one of a half-dozen U-High seniors invited to take courses at the College in 1932–33 (“one of the six guinea pigs,” he joked). As an undergraduate he wanted to be a reporter and poured his time into the Maroon. Unable to find a job after graduating in 1937, Morris stayed in the neighborhood and started a magazine called Pulse. That September Fortune sent Bernard Hoffman, a Life magazine photographer, to campus for a story about the University, and Morris assisted him for $25 a week. That was his first connection to Life, where he worked with some of the best photographers of our time, resulting in some of the most important pictures, like Capa’s images of the D-day landing on Omaha Beach.

What do the greats have in common, people at both screenings wanted to know. Morris answered the Logan Center audience with a story. In a London hotel room during World War II he was talking to Capa and Ernst Haas about what makes a good photographer. “And Ernst said firstly, a brain. Secondly, an eye. And thirdly, a heart.” Morris underlined the point in his own words. “I think the great photojournalists need to first have the intelligence and think what the picture is all about,” not merely clicking away. Then the eye and the heart, he suggested, go hand in hand. “There’s a story wherever you look if you look at it with sympathy.”