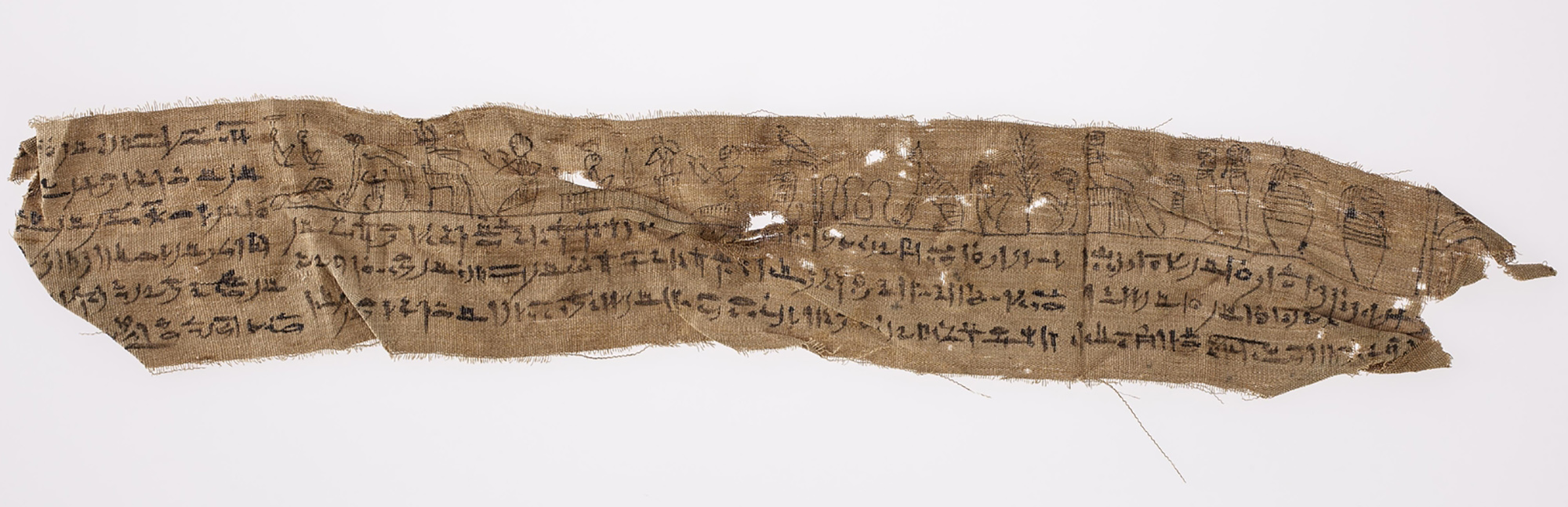

This bandage, including text and images from a common Book of the Dead spell about the creator god Atum, would have been wrapped around its owner prior to burial. The Book of the Dead was not a book in the modern sense but a compendium of spells appearing on a range of surfaces including papyrus scrolls, statues, and tomb walls. (Photo courtesy the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; OIM E19443A).

Egyptian Book of the Dead comes alive at the Oriental Institute.

The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, on display at the Oriental Institute Museum through March 31, is shrouded in mystery and misunderstandings.

“First, the Book of the Dead does not conform to our typical expectations of a book,” explains Foy Scalf, the head of research archives at the OI and the exhibit’s curator. A compendium of spells recorded by priestly scribes on papyrus scrolls, bandages, amulets, and other surfaces, the text was never bound together in book form. It also does not contain a continuous story or narrative. The corpus only received its modern designation as the Book of the Dead—or Totenbuch—from German scholars in the 19th century.

“Nor did the Book of the Dead focus specifically on death or the individual demise of its owner,” Scalf says. He prefers to characterize it as a guide to eternal life. “The texts are far more concerned with what happened after death and the transition to an everlasting afterlife.”

Specifically, the Book of the Dead was intended to aid the spirit of the deceased in venturing out of the body, avoiding perils in the afterlife, and ultimately assuming the form of a god. Life after death to the ancient Egyptians meant exploring the world by day and rejoining one’s mummified corpse each night—just as the sun god Re was thought to traverse the sky daily to unite with Osiris, the god of death and regeneration, in the netherworld at night. Through this process one could become literally identical with Osiris, whose own resurrection story was a founding myth of Egyptian religion and politics.

For ancient Egyptians, the Book of the Dead was nothing less than a resurrection and deification machine.

Among the dozens of objects on display in the OI’s exhibit are two 2,200-year-old papyrus scrolls, each over 30 feet long, replete with spells and illustrations. One section, somewhat faded by its use in past exhibits, depicts the final judgment by Osiris. If one’s heart, burdened by misdeeds, was found to be heavier than the feather of truth, it would be devoured by the feared goddess Ammit, a hybrid beast with the head of a crocodile, torso of a leopard or lion, and hindquarters of a hippopotamus. This disastrous outcome left one doubly and finally dead—unable to continue one’s quest to become a god.

Sensitive to the performative power of language and imagery, the Egyptians never portrayed the judgment before Osiris as unsuccessful. On the contrary, they sometimes showed gods stepping in helpfully to tip the scales. This imagery is emblematic of the general purpose of the Book of the Dead, which was to intervene in favor of the deceased.

Scalf emphasizes that the Book of the Dead was not principally about esoteric mythology. It was about real people, their hopes, and their fears. Central to the exhibit is one such person: a mummified woman from the city of Akhmim. Her bandages are not inscribed with spells, as was sometimes the practice. However, she is shown surrounded by inscribed mortuary objects, such as might have accompanied her in a tomb or necropolis. Spells were also likely spoken aloud at her burial.

The Book of the Dead served as a kind of spiritual insurance policy, filed in duplicate, triplicate, or beyond. The sheer variety of backup copies reflects a deep current of mortal anxiety—an element of common humanity uniting the viewer with an ancient woman about whom little else can be known.

The Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt runs from October 3, 2017, to March 31, 2018, at the Oriental Institute Museum.