Director Claire Scanlon, AB’93, says she tries to make her sets inclusive and democratic. “If I’m a jerk on set—throwing out commands, yelling and hollering—how on earth are you supposed to be funny in that scenario?” (Courtesy Netflix)

How Claire Scanlon, AB’93, made a romantic comedy for the modern era.

At first blush, the Netflix romantic comedy Set It Up feels familiar. Its two protagonists follow a well-worn cinematic path: they bicker, then they bond. Will they or won’t they? Of course they will.

But, like the unassuming bookstore owner or the hard-charging attorney who’s given up on love (pick your trope), there’s more to Set It Up than meets the eye. The film earned praise for its diverse casting and portrayal of an interracial romance, as well as its subtle subversion of romantic comedy expectations: the gay best friend has a sex life, and the promiscuous female sidekick is never reduced to a punchline.

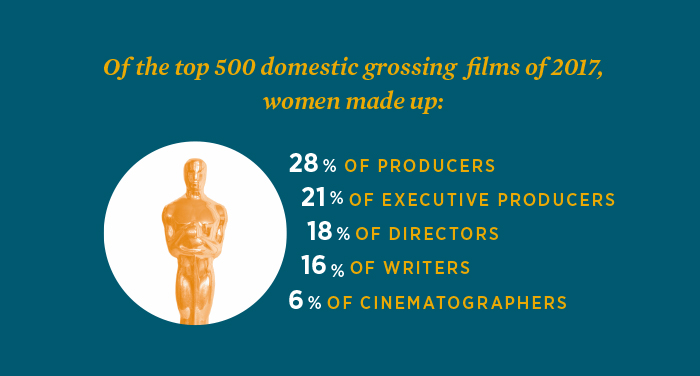

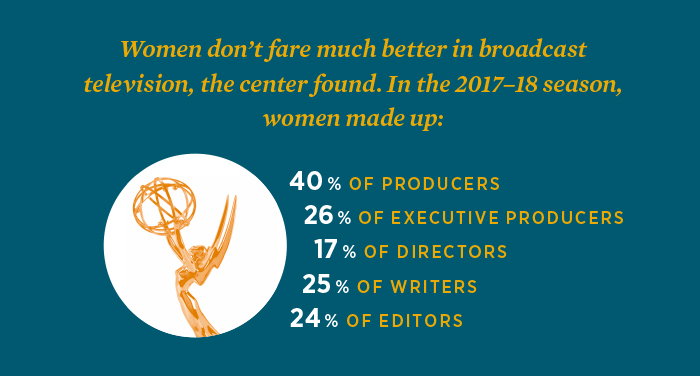

Behind the scenes, Set It Up was even more radical. At a time when women hold a fraction of key movie production roles, Set It Up was written, produced, cast, and edited by women. The film’s production designer, costume designer, set decorator, and composer were women too—along with its director, Claire Scanlon, AB’93. (As if to underscore the point, Scanlon was eight months pregnant when filming concluded. She jokes that anytime anyone complained on set, “I’d just gently turn and show them my profile, my very big belly, like, ‘Yeah, how’s it going?’”)

For her first film, Scanlon was determined to make something that felt different. Before Set It Up landed at Netflix, studios questioned the casting choices the creative team had in mind. Scanlon told them it was a nonnegotiable point for her. The film is set in New York, and she wanted it to look that way. “When I open my door in Manhattan, I see diversity. … That was really important to me, to portray the world as it is,” she says. If executives wanted a whitewashed film, “I’m not your person.”

At 46, Scanlon has arrived at an enviable point in her career—the point where she doesn’t have to compromise about the things that are important to her. “I’m not a young hot-shot 20-year-old who’s desperate for their first break,” she says. “I’m someone who can walk away from a project because I’ll be just fine.”

Still, you get the sense that she wouldn’t have taken guff at any point in her career. In talking to Scanlon, it’s obvious why she became a successful director: she is direct, and knows what she likes and doesn’t. She’s honed those instincts for decades, first as a moviegoer and fan (she’s got a deep knowledge of classic Hollywood and popular film), then as an editor, and ultimately as a director for shows including Black-ish, Fresh Off the Boat, and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. They’re good instincts, judging by the enthusiastic response to Set It Up. Netflix is famously secretive about releasing viewership data, but they’ve told Scanlon the movie has done “quite well.”

Set It Up follows the travails of Harper and Charlie, two overworked personal assistants who attempt to, in their words, “parent trap” their bosses into falling in love. Along the way, Harper and Charlie catch feelings too. It’s a tried-and-true formula that led some critics to compare Set It Up to mainstays like You’ve Got Mail (1998).

But Scanlon says that she thinks Set It Up hearkens back even further, to the romantic comedies of the ’30s and ’40s. “For me, it was His Girl Friday,” she says. “There’s a certain cadence and a rhythm to the way they speak.” She instructed actor Zoey Deutch, who plays Harper, to emulate Rosalind Russell’s rat-a-tat style. “Zoey really ran with that.”

In those classics, “women were on equal footing with men, if not one step ahead.” In His Girl Friday, Russell’s Hildy is well aware that Cary Grant’s Walter is trying to win her back. “She knows what he’s doing. She calls him out on it all the time,” Scanlon says. The fun comes from watching the back-and-forth. Will they or won’t they? Of course they will.

There’s a good reason Scanlon knows His Girl Friday so well—she edited the 2004 American Masters special “Cary Grant: A Class Apart.” It was one of several American Masters documentaries Scanlon worked on, several years after finishing film school at the University of Southern California. While cutting “Bob Newhart: Unbuttoned” and “Carol Burnett: A Woman of Character,” Scanlon got an inadvertent education in comedy. “I watched everything they ever did.”

Her mentor, documentarian Arnold Glassman, always emphasized the need for a laugh or two. It didn’t matter what the movie was about. “You cannot have two hours with no jokes,” she says.

Editing PBS documentaries was creatively satisfying but not lucrative. To pay the bills, Scanlon cut reality shows including Last Comic Standing, Top Chef, and The Apprentice. (She knows what you’re wondering, and the answer is, no. Although she’s no fan of the current president, she never saw any footage of Donald Trump saying anything particularly incriminating.)

But these numbers look different when women direct. For instance, on male-directed films, women made up 8 percent of writers. On films with at least one female director, women made up 68 percent of writers.

Between her documentary, reality show, and comedy experience, Scanlon inadvertently crafted a perfect résumé for The Office, the mockumentary about a fictional paper company in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Scanlon was hired as one of The Office’s editors and got some of her first directing experience on the show.

Editing is a delicate art. It requires balancing the artistic priorities of directors and actors with the attentional limitations of the audience. In comedy, an editor’s timing can matter as much as an actor’s. “There’s a joke that all editors have to be good dancers,” she says—because you have to have rhythm.

The Office was an editor’s heaven. Showrunners Greg Daniels and Paul Lieberstein “really respect the art of editing,” Scanlon says. Although the script’s language was sacrosanct, Daniels and Lieberstein trusted their editors to tinker with structure, for instance moving the episode’s “talking-head” interviews to play up a particular joke or story point.

Toward the end of her time on The Office, Scanlon was ready for the next challenge. Other editors from the show had directed episodes, so Scanlon felt comfortable asking if she could try too. She got her chance with season eight’s “Angry Andy” and season nine’s Halloween episode, “Here Comes Treble.”

That led to a “massive break”—a directing opportunity on the first season of Mindy Kaling’s The Mindy Project. Like Set It Up, The Mindy Project didn’t fit the Hollywood mold. At the time, “to have someone that was the romantic lead of a network show that was not white, blonde-haired, blue-eyed, and a size two was unusual,” Scanlon says. “That was a big, groundbreaking show.”

Before long, Scanlon had a hefty list of directing credits, many of them on shows created or cocreated by women, including Tina Fey’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch’s GLOW.

“I’m rooting hard for all women,” Scanlon says. “I was so glad when Wonder Woman did well.” She names several female-directed comedies—The Spy Who Dumped Me, Like Father—that she hopes will succeed, “not only because I want all comedies to do well, because I think we need more comedies out there, but in the sense that I want women-directed comedies to do well. I want women-directed everything to do well.” Otherwise, she fears, the opportunities will disappear. Men get lots of chances to make a successful movie, but for women, “it’s still that thing of, ‘We gave her a shot and it didn’t work out.’”

If editors have to be good dancers, directors have to be good at a little of everything. The job is at once intuitive and logistical. A typical day can include both counseling an actor through an emotionally complex scene and figuring out how to get permission to shoot at Yankee Stadium, as Scanlon did for Set It Up. At one point in our conversation, I offhandedly compare the work of a director to being the general of an army. Scanlon immediately pushes back. “I can’t think of an analogy less like a set I work on than the military,” she says. “Because you can’t be funny when you’re afraid.”

Scanlon’s sets are democratic. If a production assistant has a good idea, great. She also tries to protect her team by resisting the tendency to “hose a scene down”—that is, shooting it from every angle to give yourself more options. “You think that could be a good idea, but it’s folly,” Scanlon says. “Because what you end up doing is burning out your actors, burning out your crew, and then your editor gets all this mishmash with no real vision or insight into how to tell the story.”

Scanlon is, in general, skeptical of auteur theory. She tells a (possibly apocryphal) story about the director Frank Capra, who argued for the “one man, one film” approach. Capra’s frequent collaborator, the screenwriter Robert Riskin, who knew Capra wasn’t much of a writer, “was so fed up with hearing it, he threw a ream of white paper at Capra, and said, ‘Hey, let’s see the Frank Capra touch on this.’”

When Scanlon got the script for Set It Up, it “popped off the page immediately. It was just such a no-brainer.” In making the movie she fulfilled nearly all of her aspirations, with one exception: Scanlon, who grew up in Chicago, pitched for the movie to be set in her hometown.

It wasn’t in the cards. One of the film’s stars, Lucy Liu, lives in New York, and Chicago’s tax incentives weren’t competitive. “Which is too bad. Because of course I’m dying to go back to Chicago, desperate,” Scanlon says. Set It Up was intended as a love letter to Manhattan, but “I want to do a love letter to my town.”

Scanlon grew up in Boystown in the ’70s and ’80s, then a more rough-and-tumble neighborhood than it is today. Sex work was out in the open, and street crime was commonplace. She once got jumped at the corner of Broadway and Aldine.

Still, she remembers her Chicago upbringing fondly. “I would jump on the 151 or the 146, … and I would go to a movie at Water Tower Place and then I’d hit Burger King, and then I’d go to the Esquire movie theater.” She loved John Hughes’s teen-focused comedies, which were released at a steady clip throughout her own adolescence.

Scanlon spent her first two years of college at the University of Iowa, then transferred to the University of Chicago, where the classes were smaller and gave her the academic challenge she wanted. While at UChicago she got her first job in TV, transcribing the PBS series The New Explorers, hosted by legendary television journalist Bill Kurtis. Kurtis told the Chicago Tribune he remembered Scanlon as “bright, industrious, with a great future in this business, and apparently that is true.”

For the moment, Scanlon’s future involves directing the pilot and season finale of American Princess, a show about a young woman who joins a Renaissance fair, cocreated by Jenji Kohan of Weeds and Orange Is the New Black fame.

She’s also navigating fans’ calls for a sequel to Set It Up. If there were to be one, Scanlon says she’d want to follow Lucy Liu’s character, who doesn’t fully get her happy ending. “We opened a door for her, but she didn’t quite yet walk through,” Scanlon says. “So it would be interesting to see.” But Scanlon isn’t convinced there needs to be a sequel at all. “Don’t you think you should always leave people wanting more?” She’s still mulling. It’s a real will-they-or-won’t-they.