(Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

In 17th century anatomical drawings, death—and life—were much more present than in today’s medical textbooks.

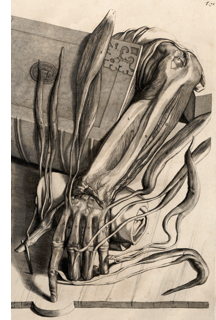

Modern anatomical images treat the human body as abstraction, says Mindy Schwartz, one of two UChicago physicians curating Imaging/Imagining: The Body as Art, an upcoming Smart Museum exhibit on representations of the body in art and in science. No such abstraction exists in William Cowper’s 1698 Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Dutch artist Gérard de Lairesse’s engravings fill Anatomy with flies, flayed skin, nooses, and rigid faces. “Most anatomists don’t really bring you into their world, because they’re trying to portray something from a pedagogical or an educational standpoint,” says Schwartz, who studies the history of medicine. De Lairesse “wants you to never forget that you’re seeing something that was hacked up.”

Modern anatomical images treat the human body as abstraction, says Mindy Schwartz, one of two UChicago physicians curating Imaging/Imagining: The Body as Art, an upcoming Smart Museum exhibit on representations of the body in art and in science. No such abstraction exists in William Cowper’s 1698 Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Dutch artist Gérard de Lairesse’s engravings fill Anatomy with flies, flayed skin, nooses, and rigid faces. “Most anatomists don’t really bring you into their world, because they’re trying to portray something from a pedagogical or an educational standpoint,” says Schwartz, who studies the history of medicine. De Lairesse “wants you to never forget that you’re seeing something that was hacked up.”

Cowper acquired (exactly how is a source of historical controversy) the printing plates for Anatomy from Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo, whose own tract didn’t sell nearly as well. This engraving shows the muscles of the lower arm and hand spread across a book and dissection table. “It’s almost as if it’s alive,” says Schwartz.

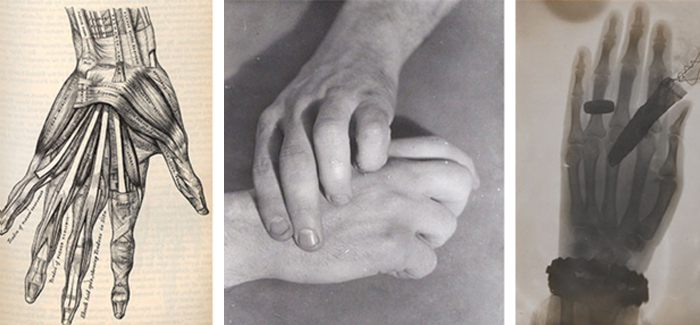

Cocurated by UChicago physician Brian Callender, AB’97, AM’98, MD’04, Imaging/Imagining opens March 25, along with related exhibits at the Special Collections Research Center and the John Crerar Library. The exhibit compares hand-drawn anatomies to modern medical images—like Wilhelm Röntgen’s 1895 X-ray of his wife’s hand, which prompted her to say, “I have seen my death.” The drawings actually measure up, says Schwartz. Cowper’s Anatomy reflects a very different world, in which medical students “lived with death in a way that we don’t.”