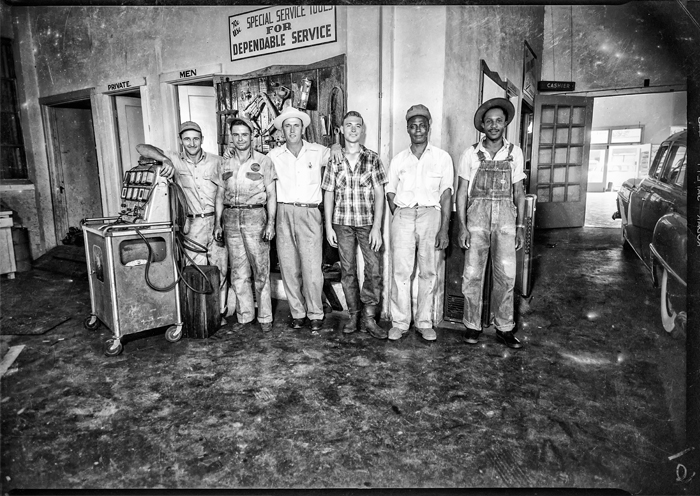

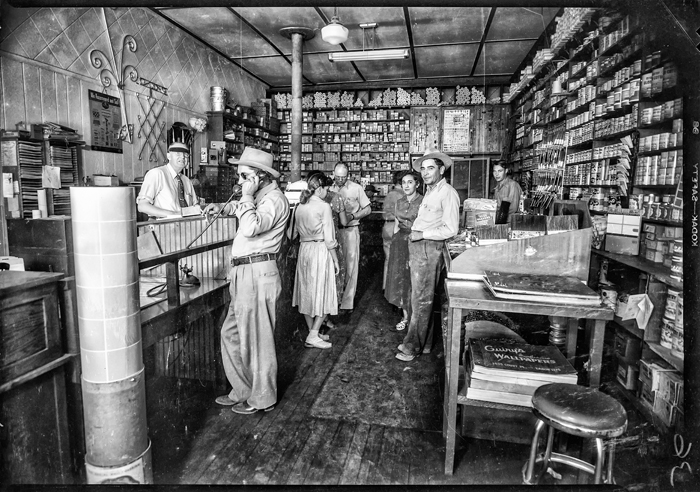

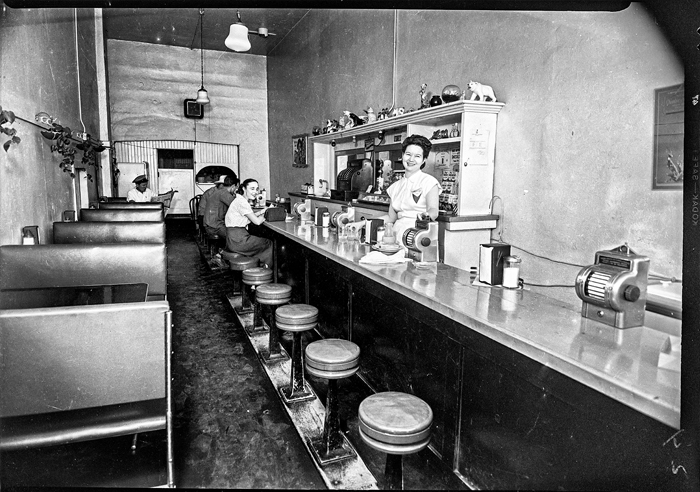

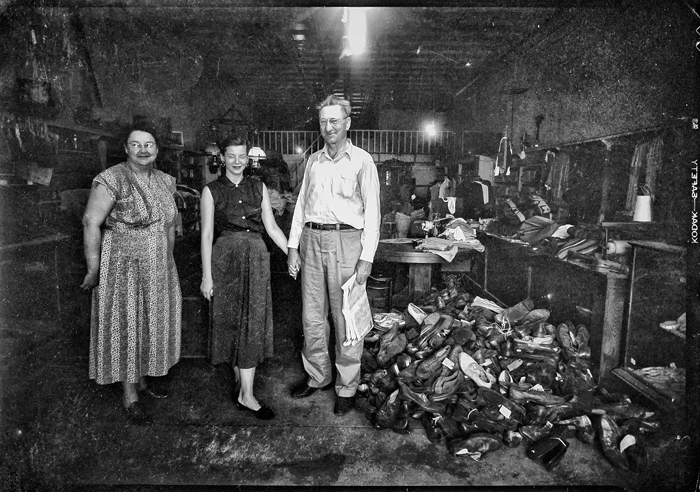

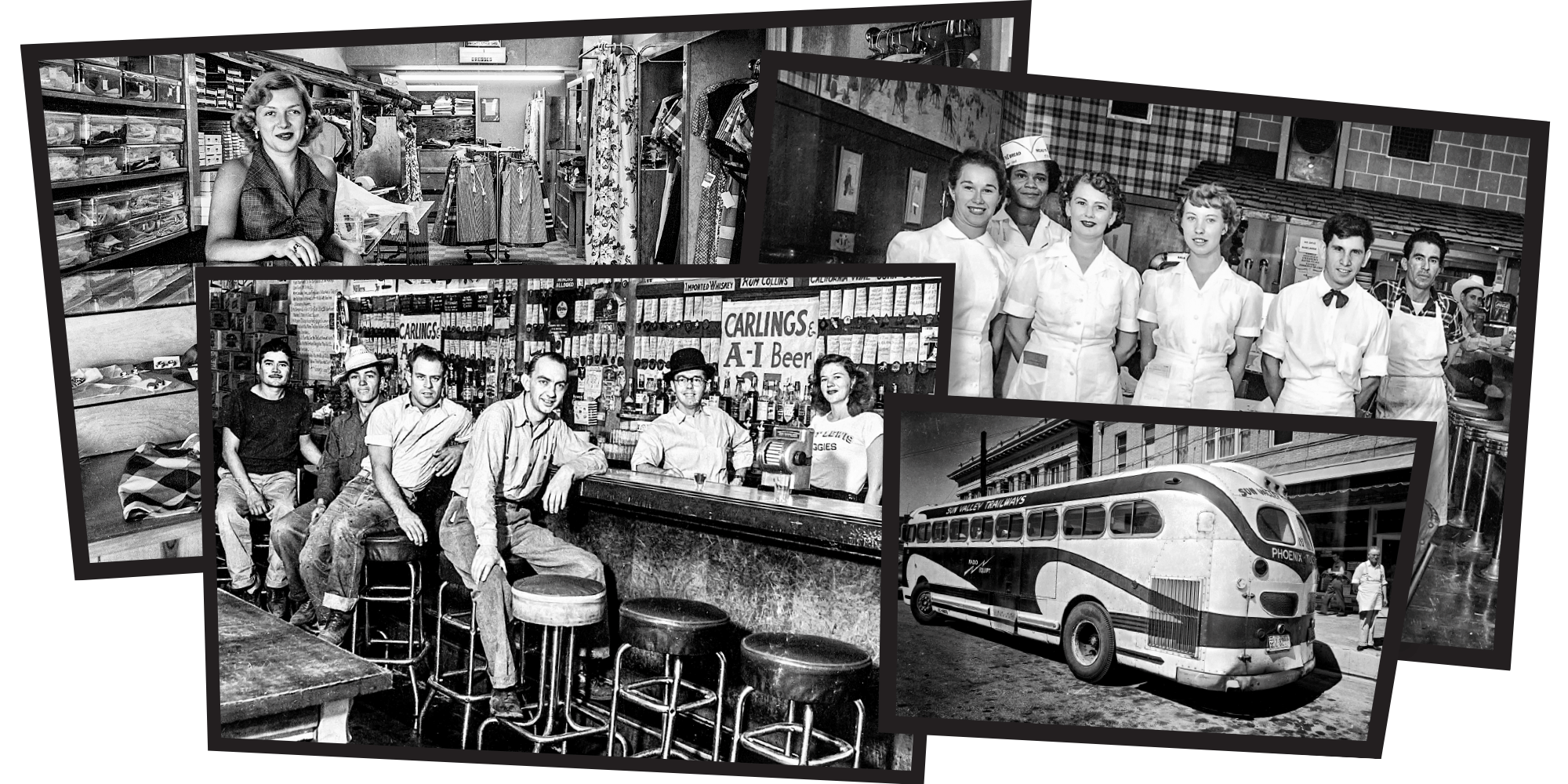

Soon after graduating from the College and marrying, Charles, AB’48, JD’58, and Irene, AB’48, Custer photographed scores of small businesses along Route 66 in the American Southwest. (Photography by Charles Custer, AB’48, JD’58)

In the 1950s, a pair of young alumni set out on Route 66 and captured a workaday America now vanished.

Growing up in WaKeeney, Kansas, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, Charles Custer, ABʼ48, JDʼ58, found his first employment shoveling coal from a railway car as a boy. Later, when he visited Topeka with his father, Raymond, a different profession caught his eye. The two ran into a street photographer hustling quick shots of passers-by. “You give him a buck and an envelope, and he sends you a picture of you walking downtown. This was a business plan,” says Charlesʼs son Charley Custer, EXʼ75.

After the trip, Charles announced to his mother, Eva, that he wanted to be a professional photographer instead of going to college. “Grandmother didnʼt even interrupt smoothing his bedsheets,” Charley remembers his father recounting. “‘Of course youʼre going to college, Charlesy,ʼ she said.”

The next years would prove them both right. First things first, Charles matriculated at the University of Chicago, as his high-school-principal father had wished and willed ever since meeting Robert Maynard Hutchins in the early years of his UChicago presidency. Raymond had thought Hutchins an “arrogant young pup” who nevertheless had good ideas, says Charley. “He wanted those good ideas instilled in my dad, and that was that.”

In a circuitous way, college led Charles to the photography career heʼd dreamt of, at least for a time. It was at the University of Chicago that he met Irene Macarow, ABʼ48, a born-and-raised Hyde Parker whose father was a bellhop in the lakefront hotels of that era while her parents operated a speakeasy out of their apartment.

The story of the photos on these pages began when Charles first brought Irene back to WaKeeney to meet his parents after the couple had graduated. The Custers instantly adored Irene, and the feeling was mutual.

During the visit, Charles proposed to Irene, suggesting they marry in a few years, after heʼd established himself and was making enough money to support them. Irene was not that patient, countering that they could both work. The next weekend they were married in the Custersʼ living room, and soon after hit the road for a “working honeymoon.”

With entrepreneurial energy and Charlesʼs Agfa box camera, the newlyweds headed south to Oklahoma and set out on Route 66, traveling through New Mexico and Arizona. Along the iconic highway, they stopped at businesses of every kind. According to Charley, they would burst in, cry “Hollywoodʼs calling! The paper wants your picture,” and set the Agfa to work photographing staff, proprietors, and customers.

In the evenings, the couple developed prints in the sink of their motel bathroom, pinning up blankets to keep out the light. The next morning, it was back to the shop or garage or salon to sell prints to the owner. They did a brisk business. Irene was “a superlative saleswoman,” Charley says, and the Agfa camera was “perfect for the job, for two reasons.” The very wide lens, together with the enormous five-by-seven-inch negatives the camera generated, took in everything, at a level of detail so minute as to be transporting. “A time machine,” Charley calls the images.

Charlesʼs photography stint was short-lived. On returning to Hyde Park in the early 1950s, he and Irene started a family, and he went into television sales and service with her brother. A few classes at the Law School to become a savvier businessman turned into a law degree and a career leading the investment services group of the firm Vedder Price Kaufman and Kammholz. Irene died in 2001; Charles in 2020.

Charley still has the Agfa camera. His dad kept one box of negatives, representing a fraction of his and Ireneʼs work up and down the historic highway. Its survival afforded this glimpse of the pictures they took, the people they met, and the places they preserved.