DeWoskin has been teaching at UChicago since 2014. What stands out is how “thoughtful and conscientious” her students are. (Photography by Jean Lachat)

Writer Rachel DeWoskin’s novel approach to empathy.

Rachel DeWoskin was 10 when she visited the Giant Buddha of Leshan, China. At 233 feet, the Leshan Buddha is the world’s largest premodern statue. For DeWoskin, it seemed like “the biggest thing in the entire universe.”

Seeing the statue was a formative moment for DeWoskin. Its size was not only shocking but humbling.

“My own life wasn’t necessarily central to the larger workings of the world, and I wasn’t a protagonist in every single story,” she recalls realizing.

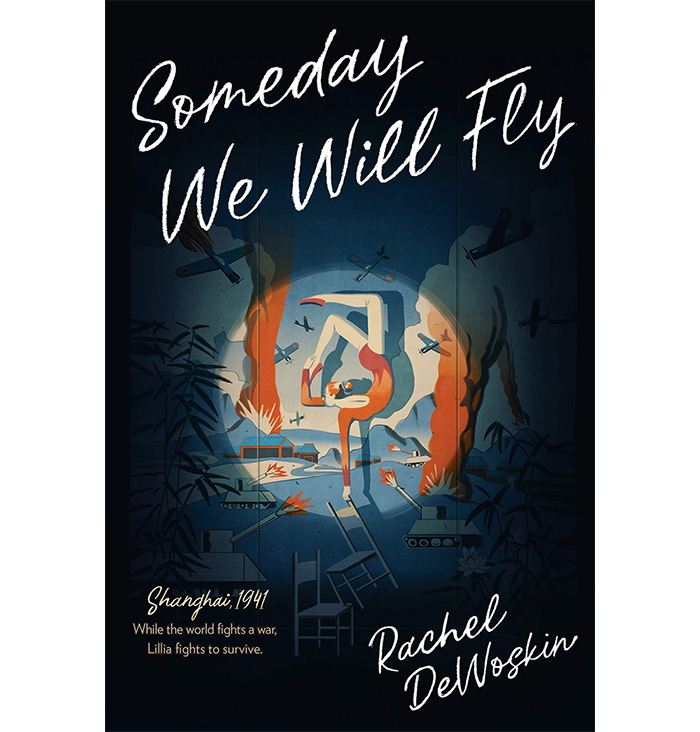

Now a creative writing assistant professor of practice in the arts, DeWoskin purposefully separates herself from the role of protagonist. Her four novels—Repeat After Me (The Overlook Press, 2009), Big Girl Small (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), Blind (Viking, 2014), and the forthcoming Someday We Will Fly (Penguin, 2019)—each explore diversity in perspective as a path toward empathy. “They’re always about being on the outside of something that you can’t fully understand,” she says.

Leshan wasn’t the only place DeWoskin arrived as an outsider. Her parents, an English teacher and a sinologist, brought her on research trips across the world. Before she could drive, DeWoskin was helping excavate ancient bronze bell sets. It was the type of experience that gifted her an appreciation for different histories and cultures.

The trips were also opportunities for DeWoskin to explore her blossoming passion for writing— though the results weren’t always profound.

“I wrote absolutely appalling poems as a kid,” she says. “My mom used to joke that I was going to grow up and work for a Hallmark card company because I was so sentimental and so rhymy.”

It was the greeting card industry’s loss when her mother’s prediction proved false. After graduating from college, DeWoskin moved to Beijing, where a chance encounter landed her a part in a Chinese soap opera. That show, Foreign Babes in Beijing, exploded in popularity, reaching 600 million viewers in one season.

But fame brought its own issues. For one, DeWoskin was only paid $80 an episode despite the show’s success. There was also the internal struggle to reconcile her real self with that of her TV persona, a character influencing a nation’s understanding of Western women.

“I had been a public figure there, and I had been a representative of American culture,” she says. “I had to grapple with the moral nuance of my participation in the show.”

She did that grappling back in the United States with her memoir, Foreign Babes in Beijing: Behind the Scenes of a New China (Norton, 2005). Though DeWoskin thinks she’s better suited to writing fiction than nonfiction, she believes her initial autobiographical work informed her later novels.

“I would argue that the craft requirements of the two are essentially identical. You have to do a lot of research to understand the world you’re creating or representing. You have to create something propulsive and shapely out of the complete chaos of human experience,” she says.

DeWoskin will go to great lengths to ensure she is portraying her characters thoughtfully. For Blind, she took braille lessons over the course of a year. For Someday We Will Fly, DeWoskin spent six summers in Shanghai, researching the realities young Polish refugees faced in the city during World War II.

The time abroad strengthened her belief in exploring the book’s central questions. “How do kids survive war? How do kids survive separation from their families? It feels unimaginable, but we have a responsibility as human beings to imagine it,” she says.

Of course, it would be easier to spend less time with each novel, but that’s not how DeWoskin has built her reputation. Former poet laureate Robert Pinsky explained to the Chicago Tribune, “her writing goes deeper than easy laughs or easy tears, with a toughness that makes her work all the more memorably funny and poignant.”

DeWoskin relishes digging into her characters’ dignity, fears, and flaws—even when they seem to oppose one another. “We each contain many contradictory versions of ourselves,” she says. “So if you can render that complexity and that kind of human contradiction in a character, then you've said something true.”

Since joining the UChicago faculty in 2014, DeWoskin has sought to empower students to speak their own truths. She insists they can create lives as writers if they want, just as she has. For those heading in other directions, she still stresses the importance literature should have in everyday life. “Reading allows for a kind of literary empathy and real empathy that are not only good for humanity, but I think also necessary for human happiness,” she says.

It’s a message that her UChicago students have been particularly receptive to.

“I came to the University of Chicago, and almost immediately, I had this imagination-bending experience of students who were consistently so thoughtful and conscientious—not just about their work, in the way that good undergraduate students can be, but about the world,” she says.

Her students’ global consciousness is a near-perfect match for DeWoskin, who has spent her life contextualizing her place in the larger world. But that awareness can also be humbling for students. Some wonder, who will listen to me? What gives any one person the right to write?

DeWoskin shares the answer she’s learned for herself.

“There's this quotation I like about how all the writing is a big body of water. Each individual writer contributes to that body of water,” she explains. “And it's responsible and reasonable to want your voice to be part of that conversation.”