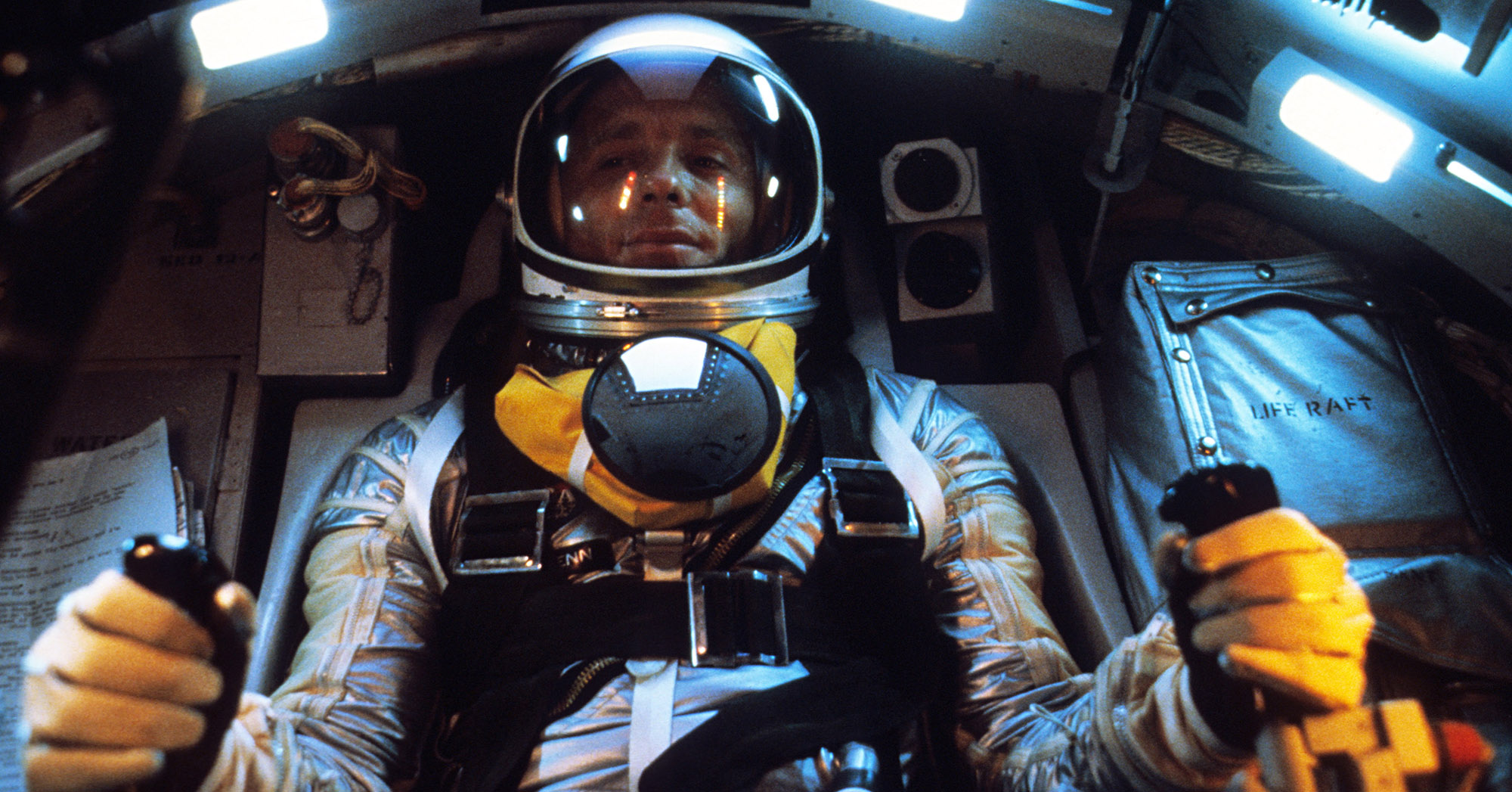

John Glenn (Ed Harris) in orbit around Earth in Philip Kaufman’s (AB’58) The Right Stuff—a memorable sequence edited by Fruchtman. (© Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection)

Academy Award–winning editor Lisa Fruchtman’s (AB’70) life in film.

“I wasn’t a real movie person or television person,” Lisa Fruchtman says of her high school self. “I was really a book person.”

Yet during her career as a film editor, she has helped shape some of the most significant and popular American movies of the past 50 years: Apocalypse Now. The Right Stuff (for which she won an Oscar). Children of a Lesser God. The Godfather, Part III. My Best Friend’s Wedding.

It wasn’t a path Fruchtman, AB’70, saw laid out before her; it’s one she discovered, step by intuitive step.

While a student at Manhattan’s High School of Music & Art, studying viola, Fruchtman favored character-driven and mostly foreign films—she names A Thousand Clowns and Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy—the kind she could catch at the Thalia on the Upper West Side, “but I never thought of making films. I was very academic.”

She found the College a perfect fit, as well as the recently launched New Collegiate Division, where she could design her own concentration in the history and philosophy of science. She created a phenomenology course with a professor at the Divinity School. When she wanted a literature course, she fashioned one on Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Albert Camus, and William Faulkner with the late Edward Wasiolek of Slavic languages and literatures and comparative literature. “I was very into the life of the mind,” she says, but—with the Vietnam War raging and the University’s relationship with the Black community in Woodlawn at a nadir—also “politicized.”

As graduation approached, Fruchtman was conflicted: Science or the law? She remained politically engaged while working as a lab assistant—her lab was run by a professor active in Science for the People, which had grown out of the antiwar movement—and inevitably got to know the members of Kartemquin Films, a collective focused on making documentaries about social issues, such as labor unions and the treatment of the elderly. (Kartemquin, which included Gordon Quinn, AB’65 [Class of 1964]; Stan Karter, EX’66; Jerry Temaner, AB’57; and the late Jerry Blumenthal, AB’58, AM’59, hit the national scene in 1994 with Hoop Dreams.)

Kartemquin is where Fruchtman discovered film editing. “I saw this craft that I never even knew existed, which was a … combination of analytical thinking, cerebral thinking, and creative thinking,” she says. Kartemquin took her on as an unpaid apprentice and eventually, “because they were great guys,” as a paid assistant. By the time her then boyfriend—now husband, Norman Postone, MD’72—headed to Montreal for his medical internship, Fruchtman had learned enough to land a job at the National Film Board of Canada.

“I still didn’t think I was going to do it as a career,” she says. “I thought that I was just stalling, honestly, until I could decide what to go to graduate school in. But working [at Kartemquin] was really the beginning of my great film education.”

After Montreal, Postone accepted a residency in San Francisco. It wasn’t the best time for Fruchtman to relocate to the Bay Area: the public TV station had just closed, putting a lot of documentary editors out of work. But it was also home to director Francis Ford Coppola’s production company, American Zoetrope, and Fruchtman “lucked into” a short-term opportunity on the film he was shooting, The Godfather, Part II.

At 22, Fruchtman had never heard the term “lined script.” It turned out to be a copy of the script that includes detailed notes—taken during shooting by a script supervisor—on the different angles and shot types (long shots, close-ups on different characters, number of takes) for every scene in the movie. That way an editor knows what footage he—not often she, in those days—has to work with. Fruchtman was brought onto the film to review the footage and redo the lined script for a complicated and crucial sequence: up-and-coming gangster Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) stalking the neighborhood enforcer, Don Fanucci, from the rooftops of the Lower East Side.

After completing the assignment, Fruchtman interviewed to work as an assistant to Richard Marks, one of the film’s editors. “I did not think that I was interested in feature films,” Fruchtman says. “I actually had not ever seen The Godfather part one.” But she got the job—and a crash course in big-time moviemaking.

In those days, the assistant’s job was to keep track of every piece of film—the reels and reels of shot footage and all the small bits, called trims, created when the editor started cutting. And the assistant had to be right there next to the editor, handing them what they needed when they needed it. Fruchtman compares it to a nurse assisting a surgeon. It was grueling work, she says, but essential to learning the literal, physical craft of editing. “You put this scene, this shot, together with that scene, with that shot, and it works or it doesn’t work. You take it apart, try a different take.”

Marks recruited Fruchtman to be his assistant on Coppola’s next venture, Apocalypse Now. This time she had a request: Could she have some scenes to edit herself? He gave her a few he figured wouldn’t be in the final film. Fruchtman worked on them at night, after assisting Marks all day.

Some of her scenes made it into the final cut, including a USO visit from a trio of Playboy Playmates, who helicopter into the heart of the jungle and unleash pandemonium before being whisked away—the fall of Saigon foreshadowed as unnerving frat party farce. Coppola had shot the sequence with eight separate cameras, which Fruchtman shaped into just over five indelible minutes. “I did make the scene sexier than it had been before,” she says with pride. As the only woman on the team and the youngest, “I wasn’t afraid to do that.” Coppola liked it too. When another editor left during the film’s grinding two-and-a-half-year production, Fruchtman asked to interview and was hired to replace him—“very much still the junior editor,” but an editor nonetheless.

Apocalypse Now shared the top prize at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, but its critical reception in the States was mixed—“an adventure yarn with delusions of grandeur,” wrote the New York Times. The film has only grown in stature over the years and now sits at number 30 on the American Film Institute’s list of the greatest American movies. (You’ll also find it at number three in the Motion Picture Editors Guild’s CineMontage Magazine list of the best-edited films of all time.) Like many of her colleagues, including Coppola, Fruchtman recalls her experience on the movie as both “wonderful” and “excruciatingly difficult.” She also realizes her luck at being part of it in the first place, knowing that it would have been harder to climb the rungs in the LA studio system. Apocalypse Now was a Hollywood movie, but the postproduction work, including editing, was done in San Francisco—a different, less hierarchical environment. “It wasn’t that I was determined to be in the movie business,” Fruchtman says. “It’s that I just had remarkable opportunities very early on.”

That Bay Area film community also included writer/director Philip Kaufman, AB’58, who in the early 1980s was prepping an adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1979). Fruchtman had read the book—“fantastic”—and went in for an interview with Kaufman.

“Phil felt like a friend and colleague right from the beginning, I think, because of our shared background at Chicago,” Fruchtman says. Despite the decade-plus that separated their time at the University, she feels the connection tipped him off about her thinking process and what interests she would bring to the movie.

Fruchtman and the other editors divvied up the scenes based on what subject matter each of them would have to master. The test pilot sequences? Time to learn about airplanes. The astronauts? Welcome to rocket school. One of Fruchtman’s sequences was John Glenn’s three orbits around Earth. She had two requirements: the scene must stick to Glenn’s real flight transcripts and, per Kaufman’s brief, “it has to be about wonder. It has to be about being out in space for the first time, looking down at Earth for the first time.” How to do that was up to her. The sequence required weeks of creative trial and error with an array of raw materials, including a model of the Friendship 7 capsule manipulated on strings, matte paintings, NASA footage of Earth, a moonrise animation by the late experimental filmmaker Jordan Belson, and Ed Harris’s awestruck performance.

Creating big feelings was the prime directive on The Right Stuff, Fruchtman says. “It appears to be a story about all of these incredible achievements. What it really is is a story about a kind of ephemeral thing called ‘the right stuff,’ … which is an emotion, which is a kind of quality, a quality that’s based on courage.”

The film earned Fruchtman’s team the Oscar for best editing. Still, she had to lobby director Randa Haines (and her own agent) for her next feature, because it was such a change of pace from the big films Fruchtman had worked on previously. But she wanted to stretch herself.

Children of a Lesser God—Fruchtman’s first time editing solo—is a romance between a teacher for the deaf (William Hurt) and a deaf woman who works at the same school (Marlee Matlin). The film offered unique challenges. To make sure hearing audiences could understand the film, Hurt had to speak aloud what he and Matlin signed. The filmmakers had also decided that a deaf person should be able to watch the film and see every moment of signing. That essentially meant that Fruchtman had to edit in two languages simultaneously. “I thought of it as cutting with three different combs, you know,” Fruchtman says. “Cutting for clarity, cutting for rhythm, and then cutting for emotion.” The movie received several Oscar nominations including for best picture, best actress (Matlin won), and best screenplay—but not for editing.

As proud as Fruchtman is of her work on the film, she understands why it didn’t draw the attention of some of the other, bigger movies she’s worked on. The Right Stuff and Apocalypse Now pack a lot of sound and action into every frame. She compares Children of a Lesser God to a solo violin performance; so it’s appropriate, Fruchtman says, that it’s “invisible to people, what actually had to be done to achieve that movie.”

Cut to 2005. Fruchtman had continued building her feature editing credits—The Godfather, Part III; The Doctor (a reunion with William Hurt and director Randa Haines); and My Best Friend’s Wedding, to name just three—and she was busy editing different projects for HBO Films. But ever since participating in an American Film Institute’s Directing Workshop for Women, she’d kept her eyes open for a project to direct. She felt she’d found it in Ursula Hegi’s novel Stones from the River (Poseidon Press, 1994). Fruchtman appreciated how the book asked big questions—“How did the Holocaust come about? How did ordinary, decent people go in this direction?”—by focusing on a small town in Germany between the two world wars. HBO had funded a screenplay, but after changes in the division, the project stalled. Fruchtman spent several years working to get the project moving elsewhere, with no success.

In 2010, during that frustrating process, Fruchtman happened upon another story. She heard about Kiki Katese, a theater director from Rwanda who had started that country’s first all-female drumming troupe, made up of women from both sides of the 1994 genocide. Katese now wanted to help the women open Rwanda’s first ice cream shop.

Fruchtman, trying to make a fictional movie about how individuals made the Holocaust possible, saw this true story as its mirror image: “How do people come back from a genocide with their humanity intact?” At the same time, Fruchtman thought a small documentary would be a good move after working so long to make a big, ambitious feature. “Of course,” she says, “there are no small movies. There are no easy movies.”

With her brother Rob, a documentary filmmaker, Fruchtman spent a year and a half in 2010 and 2011 traveling back and forth to Rwanda. They documented the stories of different women involved in the troupe and the launch of the ice cream shop, Inzozi Nziza, which translates as “Sweet Dreams”—the name Lisa and Rob would give to their film.

Surprisingly, Fruchtman says, the editing was one of the hardest parts of the project. “It had the genocide and it had ice cream. It has a lot of joy and a lot of sadness. Finding the right rhythm and the right weave of those stories was really quite difficult.” Sweet Dreams premiered at the United Nations headquarters in New York in 2012 as part of the 18th commemoration of the Rwandan genocide and has screened at film festivals around the world, bringing broader attention to Katese’s initiatives.

Fruchtman has ideas for other documentaries she hopes to direct or produce. Dramatic films too, even a limited series—“a whole new world for me,” she says. As an editor, she’s no longer looking for two-and-a-half-year tours of duty, so she’s sharing her expertise as a consultant on films that have gotten, she says, “just a little bit lost.”

After almost half a century cutting and shaping films, Fruchtman helps remind other filmmakers that editing is about going through “a process of play and discovery without getting too lost. And it’s a very, very fine, very fine line.”