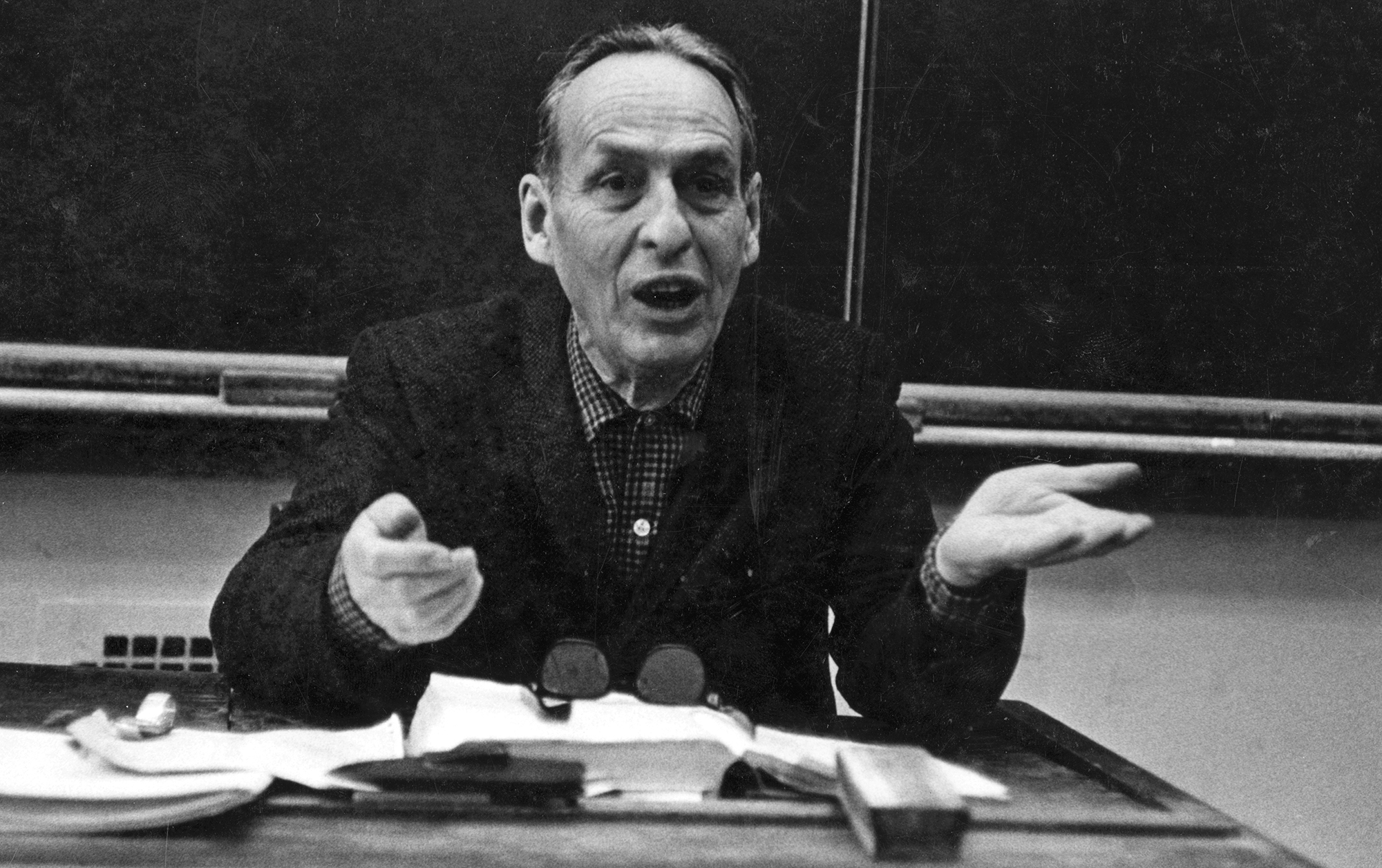

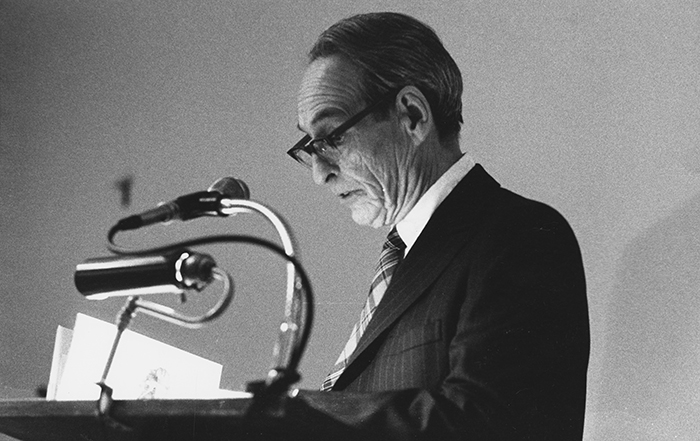

When she was an undergraduate, Leslie Travis, AB’73, took a series of photographs of Maclean in his element: the classroom. Another photo from this group appears on the cover of Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers. (Photography by Leslie Travis, AB’73; Copyright 2024, The Chicago Maroon. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.)

Before A River Runs Through It made him just plain famous, Norman Maclean, PhD’40, was UChicago famous—and UChicago beloved.

Norman Maclean, PhD’40, was many things: the most decorated teacher of undergraduates in UChicago history; author of the first original work of fiction published by the University of Chicago Press; and a sage to literary-minded anglers the world over.

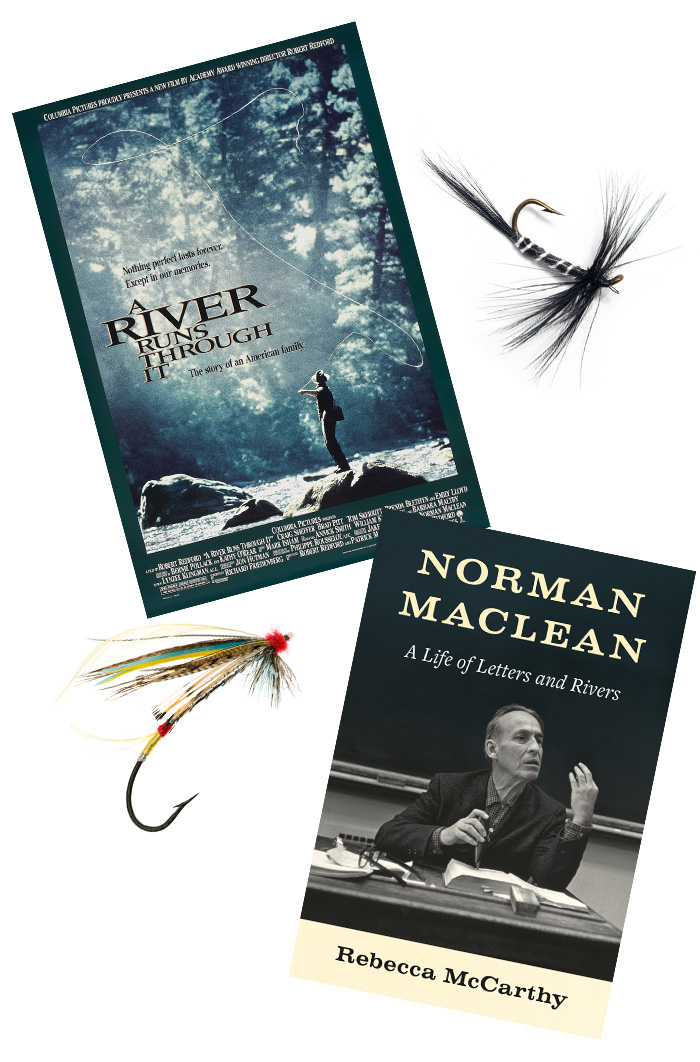

Until now, however, Maclean was not the subject of a biography. Rebecca McCarthy, AB’77, has changed that with the publication of Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers (University of Washington Press). (Read an interview with McCarthy about how the book came to be.)

It feels overdue for such a figure. At UChicago his three Llewellyn John and Harriet Manchester Quantrell Awards for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching are unmatched. Thirty-four years after his death, his iconic book A River Runs Through It and Other Stories (1976) continues in print, with more than a million copies sold. The title novella’s status as a modern classic was further cemented by Robert Redford’s acclaimed 1992 film adaptation.

McCarthy brought to her task all the usual biographer’s methods, speaking to scores of sources and combing her subject’s papers, down to the notes he kept as secretary of his condo board. But she also wrote from personal experience.

She first met Maclean while visiting her brother in Seeley Lake, Montana, Maclean’s summer retreat. The 16-year-old McCarthy impressed Maclean with her poetic talent, and he took her under his wing, reading her work, offering candid but encouraging critiques, and talking her out of vague plans to attend the University of Montana. The place for her, Maclean counseled, was the University of Chicago. “A strong, powerful woman like yourself, a poet, they would love you,” she remembers him saying.

“What I didn’t know then,” she writes in the book, “was that only the previous year, Norman had been hospitalized a few months for depression.” He had watched his wife, Jessie, suffer a protracted decline from emphysema and esophageal cancer and had lost her in 1968. He was soon to retire from teaching and could not foresee the literary success to come. In retrospect, McCarthy writes, “I think I helped Norman continue to feel healthy because I was an eager young person he could encourage and influence. I was a project.” She did come to the University of Chicago, where the two became friends.

In the chapter reprinted here, McCarthy narrates the beginnings of Maclean’s career at UChicago. Known as an inspiring teacher of undergraduates—inspiring both love and fear—he published no scholarly books and only a few articles. Holding himself to the impossibly high standards set by his exacting father, Maclean spent a career searching for the story that could realize his ambitions. He found it at last, McCarthy shows, in A River Runs Through It. When he finished the novella, “he knew it was fabulous,” she said at a reading in Chicago this May. “He didn’t need anyone to tell him.”—L. D.

Excerpt

When Norman began his career at Chicago, it clearly wasn’t a “publish or perish” world. Teddy Lynn, a beloved teacher in the English department, didn’t even have a PhD. Norman wrote little for a decade, though he did take a lot of photographs, of colleagues, family members, and friends in Chicago. Shooting pictures was a way to delay writing his dissertation, which took ten years to complete. On the day of convocation, when he was to receive his hood, he received a letter from Dudley Meek, a friend and publishing executive with Harcourt, Brace and Company. He promised to treat Norman “with the respect due one who has come up unscathed from the torture chambers of [Ronald S.] Crane and Company.” At an upcoming meeting, Meek told Norman he would “see whether a PhD-vocabulary has replaced your very artistic profanity. If I don’t hear a profane phrase turned with telling effect, I’ll believe that society has lost a true artist.”

In the 1940s, Norman was exhausted by administrative and teaching duties as well as from helping to care for his two small children. Standards and expectations changed after World War II. His teaching load was immense—three classes each quarter, usually Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and nineteenth-century poetry. Although he attended several defenses, Norman never directly supervised a doctoral dissertation, though he did offer advice to many graduate students. In the 1960s and 1970s, doctoral candidates in the English department at Chicago had to pass the 75 Book Exam before continuing on to a PhD. The books were drawn from every genre and period—plays, prose, and poetry, from Aeschylus to Tennyson to Orwell—and any departmental faculty member could drop in during any student’s oral exam and ask any question. It was an incredibly fraught experience for graduate students. Norman was known as a fair, and supportive, attendant who wanted students to succeed, but he still managed to scare the bejesus out of some of them.

PhD candidate Robert Cantwell [AM’67], who later taught at UNC at Chapel Hill, recalled that during his exam in the 1960s, when Norman entered the room, “my aqueous brain was suddenly and swiftly evacuated.” Norman tossed Cantwell a softball question, “To what does Dr. Johnson appeal beyond criticism?” Cantwell said that even though most English undergraduates at Chicago knew the answer by heart, he was so discombobulated by Norman’s presence that he couldn’t recall that “there is always an appeal open from criticism to nature,” much less anything else. “I don’t remember how I got through the exam, which transpired as in a dream, but somehow I passed it.”

Terry Meyers [AM’68, PhD’73], who earned his MA in 1968 and became a professor at William and Mary, said that during his exam, he “ran into problems” with Professor Elder Olson [AB’34, AM’35, PhD’38], “who had a disconcerting way of asking questions and then cutting the responses off if he thought the candidate could answer the question” or if he thought the candidate couldn’t. Thrown off by Olson’s methods, Meyers felt he was “on the ropes” and “about to go down for the count” until Norman intervened, wrestling away the interrogation and then asking questions “that let me formulate what I wanted to say without the pressure of having the rug pulled out from under me each time I started. I’ve always been grateful to him for rescuing me.”

Throughout his long career at Chicago, Norman invested his time and talents primarily in teaching college students. The letters, notes, and recommendations he sent to and for undergraduates are voluminous—literally hundreds of documents. That’s what he was writing, letters for students and letters to friends and colleagues, letters to awards committees, letters to prospective graduate students, letters to employers and more letters. But he wasn’t writing scholarly papers. From the 1950s onward, said [English professor] Gwin Kolb [AM’46, PhD’49], whose area of expertise was the eighteenth century, “there was the feeling among some people that Norman wasn’t a scholar because he never published a scholarly book.” But as his output in the 1950s shows, Norman could “do scholarship,” Kolb told me. “He was very solid.”

Published in 1952, Critics and Criticism, Ancient and Modern, featured chapters by Ronald S. Crane and his neo-Aristotelian acolytes. That group included Norman. His first chapter in Critics and Criticism is “From Action to Image: Theories of the Lyric in the Eighteenth Century.” It’s rigorous while reflecting Norman’s sly humor: “Few of the late-eighteenth-century writers who deluged the printing facilities with lyric stanzas and sonnets left much in the way of critical opinion, and this is unfortunate. Not that great critical systems abounded then which perished for want of a publisher.” A footnote in the essay indicates that Norman’s chapter on the eighteenth-century theories of the lyric is part of a larger project he’s planning that “will follow the long discussion about lyric poetry from the time when it first became audible to the present” and will relate criticism to philosophy and poetry. Unfortunately for scholars who focus on the lyric, Norman never completed this larger study. Did he think he wasn’t up to the task? Or did he simply lose interest? He seems to have been an author in search of the right story.

His second book chapter, “Episode, Scene, Speech, and Word: The Madness of Lear,” reads like a poem itself—in places, it scans. As in his other chapter, Norman is funny as well as insightful. Consider: “We must recognize, however, that a certain number of critics read King Lear in such a way that Gloucester’s lines are taken as a condensation of Gloucester’s and Lear’s and Shakespeare’s ultimate ‘philosophy,’ although this seems to me to be an interpretation of another book, possibly one written by Hardy.” Gloucester famously claims, “As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods; / They kill us for their sport.” As Mary Ellis Gibson [AM’75, PhD’79], the Arthur Jeremiah Roberts Professor and Chair of English, Colby College, a scholar of nineteenth-century literature, told me in a 2015 interview, Norman here is skewering existential critics without naming them—he reads the play’s ending as about tragic love, not existential angst. Norman goes on to note, “Scholars are still in search of the exact meaning of certain speeches in each of Shakespeare’s great tragedies—and we should like to assume that those who saw these plays for the first time did not have perfect understanding of all of the lines—but so great was Shakespeare’s power to conceive of action from which thought and feeling can be readily inferred that all of us know Lear, Hamlet, and Macbeth more intimately than we know many men whose remarks we understand perfectly.” To Gibson, Norman here sounds like someone who was tired of faculty meetings and administrative claptrap. He defends mystery—and intimacy.

“I still admire the usefulness and the critical acumen of the essay—after all these years,” Gibson wrote to me. “But I admire the essay’s structure and its poetry even more. Norman makes a strong, if implicit, argument that only a fool would prefer the Folio version of his favorite line, rather than the Quarto version (there are two equally authoritative versions of Lear which differ in important respects, including this line). The single line Norman parses, ‘Hast thou given all to thy two daughters? And art thou come to this?’ he reads brilliantly. From the Quarto, as the more beautifully done. He reads the line all the way down to the scansion.”

This essay still holds water more than seventy years after it was published. Clearly, Norman could do scholarship. Teachers at Dartmouth and Chicago had approved of his writing. David Lambuth, who wrote The Golden Book on Writing, thought Norman wrote so well that he hired him after graduation to teach freshman composition. James Dowd McCallum sent him a note after Norman sent the Lear essay: “The essay marches steadily to your conclusion. It is compact, frequently pithy, and even moving.” Norman’s dissertation had been solid enough to prompt a letter from Professor Ronald Crane himself a few years later, urging Norman to rework his ideas into a book. “What I want to convey to you now is the very great satisfaction I have had in the clarity of your narrative and in the maturity and wit of your reflections,” Crane wrote. “You have the groundwork of a first-rate book. May it be finished soon!” Despite this hearty thumbs up from his major professor, Norman never did transform his dissertation into a book. He didn’t share these positive opinions—or at least he didn’t act on them.

I believe the years of having his father as a teacher made him his own worst critic. He tells the story in “A River Runs Through It” of having to write daily themes for his father, gradually paring down what he wrote until his father found it satisfactory and then threw it away. Little that Norman wrote was good enough for him—or for anyone else. As he told [English professor] Richard Stern: “I know my writing has more than its share of blemishes. Words to me are things you take chances with both in what you say and how you say it, and these long shots don’t always pay off.” And spending days in the stacks as many scholars did just wasn’t something he wanted to do. He wanted to spend his summers in Montana, not in the Bodleian or Beinecke library.

Perhaps most importantly, I think Norman was intimidated by Ronald Crane, who was part of the sweeping changes that Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins made during his administration in the 1930s. Hutchins divided the university into four branches—physical science, biological science, social science, and humanities, with the college as a separate entity. Richard McKeon, who had arrived from Columbia University to teach philosophy, became the dean of the Humanities Division, and in 1936, Crane became the chair of the English department—he had joined it in the 1920s. Both men advocated jettisoning the traditional way of studying literature and instead applying Aristotelian methods of logic and analysis to texts. His acolytes and he were called the neo-Aristotelians. In place of literary history, students would focus on literary criticism. Younger faculty members, including Norman, embraced Crane’s ideas, while some of the older department members did not. The disciples called the chairman “boss.”

Crane was a teacher who, according to Elder Olson, “presented not a mass of facts but a narrative” and an inquiry into the construction of his own narrative. Crane raised questions: What was a fact? When did a fact become evidence? What kinds of history are there? What was a hypothesis? In a seminar, according to Crane, participants pursued questions for which the professor didn’t have answers, and they developed insights into foundational ideas underlying scholarship. Crane’s ideas about literary criticism had a profound effect on the teaching of English literature on university campuses across the country. I think Norman felt he couldn’t meet Crane’s expectations, so he decided not to try. Perhaps he found he didn’t agree with the boss’s ideas but didn’t want to challenge him.

“Crane was a serious thinker,” said Herman Sinaiko [AB’47, PhD’61], who served as both the undergraduate advisor and a director of the Committee on General Studies in the Humanities after Norman stepped down. “Norman was a deep thinker. That was part of his problem—he felt he just couldn’t measure up.”

With Crane in charge, the English department in the 1930s developed a reputation for toughness. There was no way anyone would think that someone as intellectually challenging—and sometimes verbally combative—as Norman, W. Rea Keast [AB’36, PhD’47], Elder Olson, or Crane himself was the stereotypical effete English teacher. The department required its college students to pass a week’s worth of exams at the end of the senior year. These included six hours of open-book tests and a six-hour test on works randomly selected from two hundred titles. Among them were Aristotle’s Poetics, Darwin’s Origin of Species, and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire as well as Moby-Dick and Bleak House. Students didn’t know which titles would be chosen, so as they started their junior year, they began reading like crazy. To prepare for the six-hour writing marathon, they picked courses that would help them interpret the texts. Norman’s classes became known as ones that fit the bill.

At the beginning of every quarter, students would jam into Norman’s classroom on the first day, whether or not they were registered, hoping he would let them stay. This didn’t happen—the rooms were too small to accommodate a crowd. Like the other Aristotelians, Norman used the Socratic method in his teaching. One student remembered how she would blather a pretentious, banal answer, and Norman would respond: “A safe assumption! A safe assumption!” If a student offered an insightful observation, one that may have contradicted what Norman had said earlier in the class, Norman would agree that the student had said something new, adding, “You’re right and I’m wrong.”

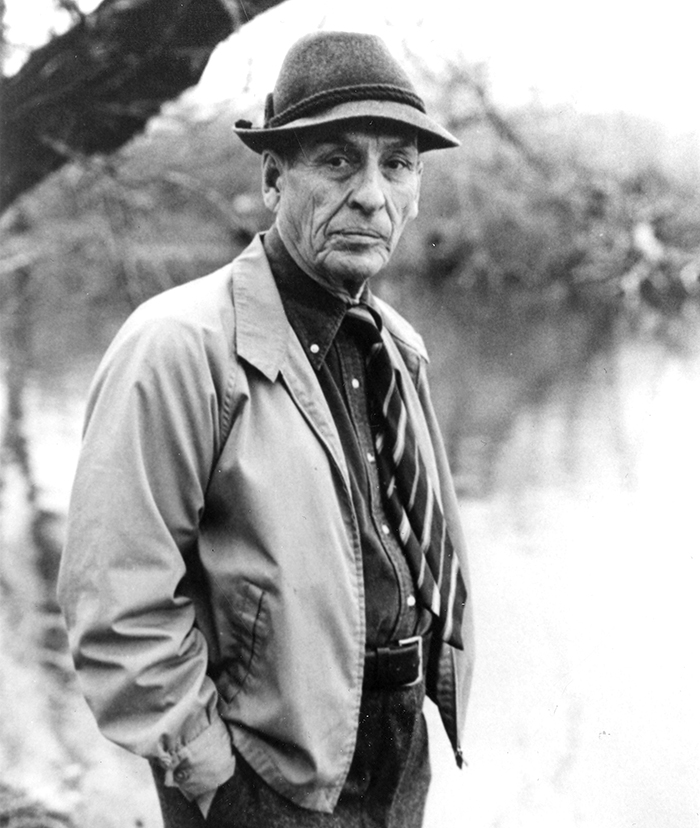

Because his scholarly output was so paltry, Norman was known as an undergraduate teacher. I know he resented being classified as a mere college teacher, and he worked hard to whittle away the chip on his shoulder. I think he felt the English department’s university faculty members didn’t value his contributions—although Gwin Kolb and Ned Rosenheim [AB’39, AM’46, PhD’53] thought otherwise. He cultivated a persona for himself—the persona of Norman Maclean, a lone wolf from the mountains of Montana, where men were men. This Norman Maclean was a plainspoken, truth-telling, profanity-spouting, chain-smoking tough guy, whose deadpan delivery could silence departmental meetings and whose stare could quiet a room of chattering students. Those who didn’t know Norman well were afraid of him. He was a campus legend a few years after he arrived on campus in 1928. Even though Norman had retired in the early 1970s, his reputation persisted. In 1974, when I was a first-year student at Chicago, some older residents in my dormitory couldn’t believe I was friends with him. They watched as he strode into Pierce Tower to leave notes in my mailbox, and they whispered about him to each other.

What did they really know about him or his background? All they knew was you didn’t want to tangle with Mr. Maclean.

Excerpted from Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers by Rebecca McCarthy with permission from the University of Washington Press. Copyright © 2024 by Rebecca McCarthy.

Questions for the biographer

When Rebecca McCarthy visited Chicago to read at the Seminary Co-op bookstore, the Magazine spoke with her about the biography and its making. McCarthy’s comments have been edited and condensed.

How did you come to undertake this book?

I was good friends with Gwin Kolb, a close friend and colleague of Norman’s. And Gwin told me, “Becky, you need to start interviewing all the English department faculty before they die. You must write about Norman. You used to fight fires, you lived in Montana. You can do it.”

So I started interviewing: John Wallace; Ned and Peggy [JD’49] Rosenheim; Wayne Booth [AM’47, PhD’50]; David Bevington. I mean, anybody. William Veeder; Robert von Hallberg; Joe Williams; Frank Kinahan; Richard Stern. And they said, “You need to talk to so-and-so,” and I would talk to so-and-so in a different department. And then those folks would suggest others.

At Joel Snyder’s [SB’61, professor emeritus of art history and Norman Maclean’s son-in-law] suggestion, I ran a notice in the alumni magazine, telling readers what I was doing. I got a deluge of mail and phone calls from, I would say, 50 to 100 people. And they all wanted to talk about Mr. Maclean. His class was the only thing that people who finished in the 1930s still remembered. You know, “he saved my life and changed my life,” just all these testimonials.

In researching the book, you went everywhere—to Clarinda, Iowa, where Norman and his parents once lived; to Norman and his brother Paul’s college, Dartmouth; to Missoula and Seeley Lake, Montana; and to the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center in Chicago, to name a few. How did you craft all you learned into a narrative?

It was just little by little—accretion, getting all the information. And then I thought, I’ve got to fish or cut bait. I just started writing. I wrote a version that was chronological. The University of Washington Press sent it out to the first reader, and they said, “Oh, this has a lot of information.” The second reader just excoriated it. I mean, it was not helpful. It was hurtful. But I put that aside and talked to my friend Daryl Koehn [AB’77, AM’83, PhD’91], who has written many books, and I let her see what the person had written. She said, “Why don’t you take some of the suggestions? Even in this pile of shit, there might be a few pearls, right?”

So I did. And I just thought, you know what, I’m not going to write a biography, I’m going to tell a story. So people can see Norman and hear Norman and understand how he moved through the world and how he treated other people.

Norman had a lot of students who were tucked under his wing. I wasn’t the only one. Yeah, I was the only one who had fought fires in Montana, and lived in Montana, and knew Seeley Lake. But there were many other students. Bill Harmon [AB’58, AM’68] was one, and he was the longtime head of the English department at Chapel Hill. Ken Pierce [AB’63, AM’67], who wrote for the Village Voice. There are many people who were successful who Norman had nurtured in some way.

And so, when I started rewriting the book, at first I thought, I can’t. It was too much for me. So I backed up from the first version and then just shone a light on him. At first the book is me showing you him. And then it’s just him being him.

Were there other books you had in mind when you were writing yours?

The hero of what I call witnessed biography—and I love that; when it’s possible, it’s fantastic—is James Boswell. No one will ever top Boswell’s Life of Johnson. For biographies that aren’t witnessed, I love Claire Tomalin. I love her biography of Dickens. I read that, and I read her Pepys biography. She wrote a fantastic biography of Thomas Hardy. It’s great. And Norman loved Hardy too, because he made the jump between Victorian and modern poetry. And that’s what I read while I was writing.

You didn’t say what inspired me, but those books did, and a book by Candice Millard called River of the Gods: a terrific book about Richard Burton, John Speke, and the search for the White Nile. And I read Ron Chernow’s biography of Grant.

I think those are the closest. But I don’t think most of the people I’ve read have been friends with the person, so it’s kind of different.

Did anything in his papers especially catch your eye?

What stood out was the immensity of the task. Robert Caro said, “Turn every page.” I looked at almost everything. Norman was secretary of his condo association, and I read all the minutes. I mean, it was stupid, but I thought maybe he’d said something funny. There were many rabbit holes. I know a lot about [sixth president of UChicago and Maclean’s friend] Larry Kimpton that isn’t in the book—I wasn’t writing about him.

Norman kept a notebook for random thoughts. On one page, he writes that his sister-in-law Dotty Burns had died. Dotty and Kenny Burns were always at Seeley Lake in the summer, and they kind of ran the house. They did the shopping, and Dotty did the cooking, and Kenny chopped the wood, and Norman wrote. Then Dotty had a heart attack, and Norman wrote, This is a dark day, Dotty died, what do I do? Do I (a) find a woman? Do I get married? Do I (b) just fold up my house and stay in Chicago? Or do I (c) hire someone to clean and keep going? He did the third. He talked to Bert Sullivan, who was the postmistress and knew everybody, and she got him a housekeeper. It worked out. But just those questions—it was so funny to me.

In that notebook, you could see the wheels going and going about how he had written 70 pages of Young Men and Fire [University of Chicago Press, 1992]. He said, How did I write these 70 pages? He was astounded that he had written them. Then he would set pieces aside. [University of Chicago Press editor] Alan Thomas knows a lot more—he had a piece in the Los Angeles Review of Books about the writing and assembling of Young Men.

But the draft was pretty much there. Norman just couldn’t let it go. Because it was keeping him alive, and he just couldn’t let it go.