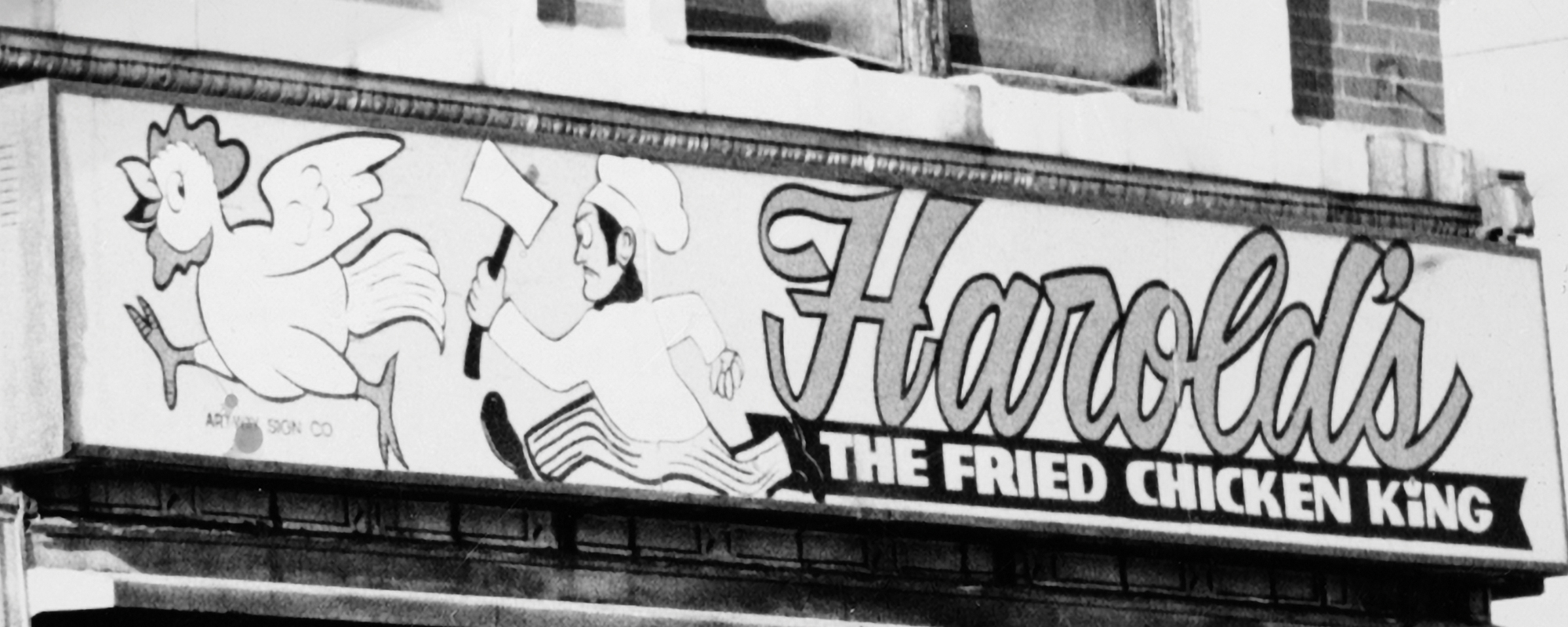

The former Harold’s location in Hyde Park at 1346 E. 53rd Street, now the site of a Target. A new book on Hyde Park history explains the origins of the beloved franchise. (Copyright 2020, the Chicago Maroon. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.)

The City in a Garden looks at the “place-ness” of Hyde Park history.

John Mark Hansen, the Charles L. Hutchinson Distinguished Service Professor in Political Science and the College, has called Hyde Park home for more than 30 years. He’s an avid cyclist who hosts two annual bicycle tours of the South Side with Dean John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75.

The City in a Garden: A Guide to the History of Hyde Park and Kenwood (Chicago Studies, 2019) is like a book version of these tours. Here are a few stops on the tour.—Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

The City in a Garden

How do you chronicle a time and a place?

My choice to tell the story of the community through the stories of individuals rests on the claim that people (our forebears and ourselves included) do not live narratives; instead, they live experiences. Each of the articles in this book links an incident or a person to a precise location, often a specific address. In many cases, I have gone to considerable trouble to identify them. In doing so, I mean to emphasize the “place-ness” of our history.

At the Beach

In July 1913, the Jackson Park beach censor, Walter Straight (5490 Ellis), arrested Dr. Rosalie M. Ladova (1370 E. 57th) on a charge of disorderly conduct. At the beach at 58th by the old German Pavilion, Ladova entered the water, doffed her skirt, and commenced to swim in bloomers. Officer Straight rowed out to her and demanded that she put on her skirt, as required by city ordinance. She replied that she would, as soon as she finished swimming.

At the Hyde Park Municipal Court, Judge William M. Gremmill (5406 Ellis) dismissed the charge. “Dr. Ladova’s suit was quite modest,” he said. “No one but a prude could object to it.”

Ladova was a rare female physician and an activist in the suffrage movement. Before the city council, she complained about a “double standard of morality. If men are allowed to wear tights, why shouldn’t women be?” The council studied the issue for almost a year, deciding finally to leave the issue of acceptable bathing attire to the police. The chief of police declared that he considered bloomers to be appropriate swimwear for women, unless he said, they were overweight.

Ladova was a Jewish immigrant from Russia. She practiced in Wisconsin and throughout Chicago. The Tribune recognized her as “a leader in the fight for women’s rights” when she died in 1939.

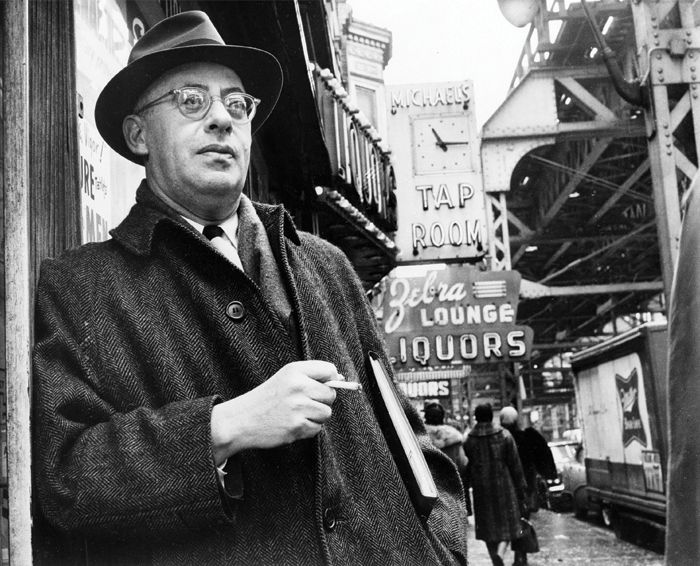

The Organizer

Saul Alinsky residence

5525 S. Blackstone Avenue

Alinsky graduated from the University of Chicago in 1930. In the thirties, he began his career as a community organizer in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. He founded the Industrial Areas Foundation (1940) and wrote Reveille for Radicals (University of Chicago Press, 1946) while living in Hyde Park (also in the same building at 5529). In the fifties, the IAF began to organize in Woodlawn, playing a role in the creation of The Woodlawn Organization (TWO).

Alinsky’s field director during the drive to organize Woodlawn was Nicholas von Hoffman (1221 E. 57th). He was later a columnist for the Washington Post and the liberal in the first pair of commentators on the “Point/Counterpoint” segment of CBS’s 60 Minutes. During the Watergate hearings, he likened President Nixon to a “dead mouse on the kitchen floor of America” and said that “the only question now is who’s going to pick him up by his tail and throw him in the garbage.” 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt fired him.

Turabian

Room 206A in Cobb Hall was the office of Kate L. Turabian, the University’s dissertation secretary (1930–58) and the author of A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (University of Chicago Press, 1937). Known simply as “Turabian,” it was and is the standard guide for research publications. A recent study identified Kate Turabian as the female author whose work is most often assigned in college courses, ahead of Toni Morrison and Jane Austen.

Harold’s

Site of original Harold’s Chicken Shack

1235 E. 47th Street

Harold P. Pierce came to Chicago from Alabama in 1943 and worked as a chauffeur for Jack Stern (1101 E. 48th), the owner of Kennedy Furniture Stores. His wife Hilda worked as a cook at the Home for the Friendless (5250 S. Ellis). On the side, they ran H&H, a small restaurant on 39th St. serving dumplings and chicken feet.

Pierce had dreamed of opening a fried chicken restaurant since the day in his boyhood when a preacher had supped with his family and ate up his mother’s entire batch. In 1950, he was discussing his plans with friends over a game of checkers at a barbershop at 69th and South Pkwy. (King Dr.) when one of them, Gene Rosen, the owner of a poultry store at 353 E. 69th, offered him some fryers to experiment. It was a success.

Pierce sold the restaurant on 39th, contracted Rosen to supply his chicken, and opened the first Harold’s Chicken Shack at 47th and Kimbark. The restaurant moved to 1106 E. 47th in 1962 when urban renewal claimed its building. Soon Pierce was known as the Fried Chicken King. He made deliveries in a white Cadillac with painted wing feathers on the doors and a papier-mâché chicken head on the roof.

Pierce invented the red and white décor for the chicken shacks. He also commissioned the logo, a hatchet-bearing man in robe and crown chasing down a bolting hen. Pierce opened a second outlet at 6419 Cottage Grove in 1964 and two others shortly after. He soon began to franchise the restaurant to friends and relatives. Pierce required the franchisees to pay him a 42-cent royalty for each bird and to buy their chicken from Gene Rosen. Otherwise, he exercised lax control. Soon the city’s Black neighborhoods were dotted with Harold’s fried chicken restaurants.

At his death in 1988, Harold’s had 40 chicken shacks. His daughter Kristen Pierce-Sherrod now oversees the Harold’s empire.