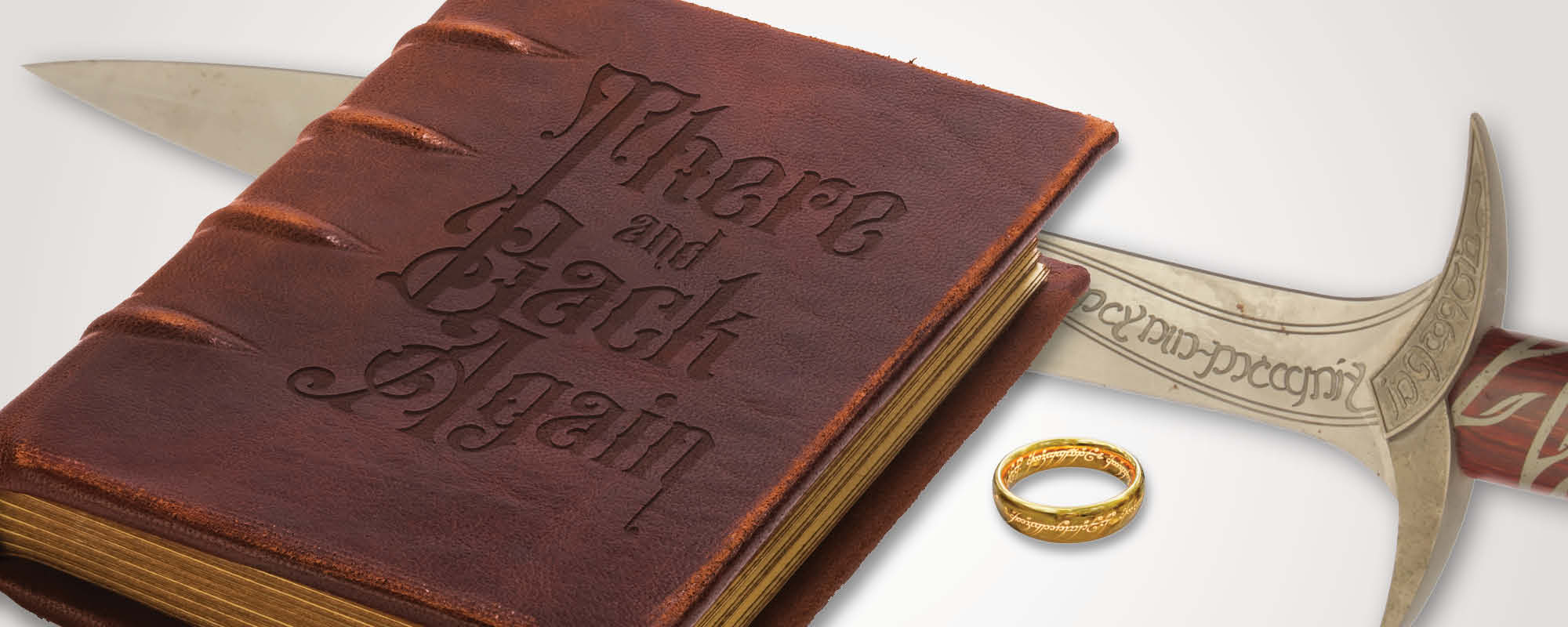

There and Back Again, the title of Bilbo Baggins’s memoir, is Eno ha Distro in Breton. (Photo illustration by Michael Vendiola)

Josh Tyra, AB’01—a language nerd in the mold of J. R. R. Tolkien—helped create a new Breton translation of The Hobbit.

When he was 17, Josh Tyra, AB’01, went on a summer immersion program to Brittany, France. A “burgeoning language nerd” (he’d already taught himself Old English, just for fun), Tyra was thrilled to discover the region had its own tongue—Breton. According to UNESCO, the Celtic language has around 250,000 speakers today, few enough to be considered endangered.

Tyra spent the summer asking everyone he met if they spoke Breton or knew anyone who did, and scouring the Breton section of local bookstores. “I returned from that trip with a whole suitcase full of Breton books, grammars, and dictionaries,” he says. He continued to independently study Breton at UChicago (“often when I should have been studying other things”) and after.

In 2001, on another trip to France, Tyra bought a paperback copy of An Hobbit, pe Eno ha Distro (ARDA, 2001), a new Breton translation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s 1937 classic The Hobbit, or There and Back Again (G. Allen & Unwin). The translator, Alan Dipode, is a native Francophone who also speaks fluent Breton. It was a lucky find. The initial run of Dipode’s Hobbit was small, and it would soon fall out of print.

Over the years, Tyra’s career followed a winding path: he served in the Army, then went to graduate school to study biblical archaeology and language. “A lot of the translation tools that I brought into this project, I learned from Bible translation,” Tyra says. (Today he works as a private tutor.)

All the while, he remained active in online groups for Breton speakers and enthusiasts. That’s how he eventually met linguist Michael Everson, whose press Evertype issues an eclectic range of titles in minority languages, including Cornish and Hawaiian.

Tyra made his pitch: Would Evertype rerelease Dipode’s Breton Hobbit? Sure, Everson told him, if you can figure out the copyright. A few Facebook messages later, Tyra had tracked down Dipode through his son. Everson got him on board—not just to reissue An Hobbit, but also to update the translation with Tyra’s help as a native English speaker.

First on the list: mild oaths. Tolkien’s characters are prone to grandmotherly euphemisms for “my god” and “my lord”: “good gracious” and “bless my soul.” Dipode had translated these with the common Breton phrase ma Doue (literally, “my god”), which didn’t mesh with Tolkien’s efforts to avoid explicit references to Judeo-Christian religion in the novel. Tyra developed a list of softer Breton alternatives—boulc’hurun (“thunderbolt”), ac’hanta (“well, then”), and biskoazh kement-all (“never such a thing”), to name a few—for Dipode to consider.

Other translation issues were more interpretative. Among Breton’s unusual features is that “humanness—being human or not human—is a grammatical category,” Tyra explains. This poses obvious challenges for a novel populated with hobbits, elves, goblins, and trolls. In Dipode’s original translation, heroic hobbits and elves were treated as grammatically human, while nasty goblins and trolls were not. It was an interesting choice, but Everson felt strongly that “rational two-legged peoples of Middle Earth should probably be treated as humans,” Tyra says.

One of the few other languages that treats humanness as a grammatical category is Arabic, which Tyra also speaks. “There is conveniently an Arabic translation of The Hobbit,” so he consulted it to see how that translator handled the challenge. “Lo and behold,” he says, good guys and baddies alike were treated as grammatically human. This, along with Everson’s conviction, proved convincing.

Then there was the problem of “elf-friend,” a term used as something like an honorific for those who have provided a service to the elves. Dipode’s original, ur mignon d’an elfed, was more or less literal (“a friend of the elves”). Tyra proposed a loftier alternative, using a word closer to “comrade”: elf-kariad.

“So that’s my contribution to the Breton lexicon, thank you very much,” Tyra says, smiling. “I made up a word for ‘elf-friend.’”