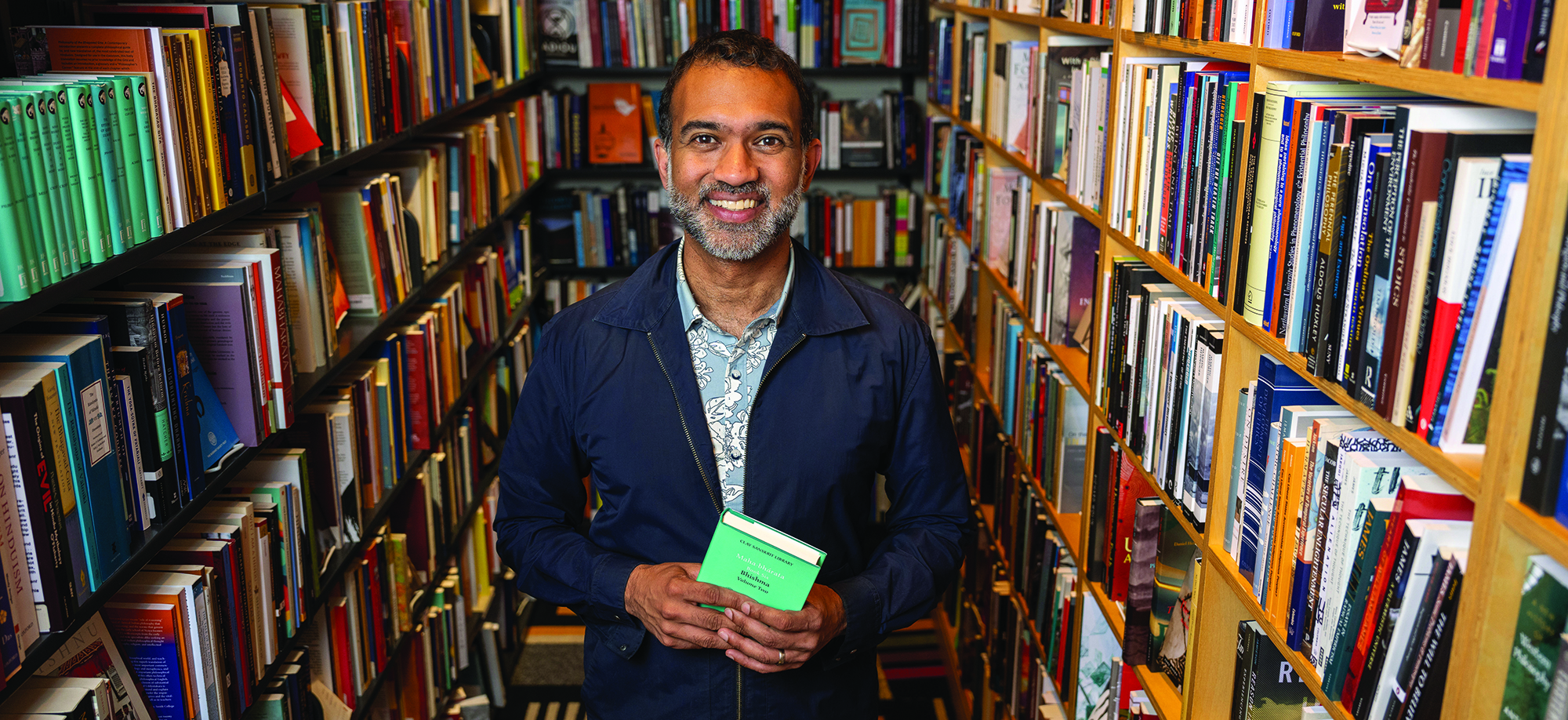

Chicu Reddy’s life in poetry.

Srikanth “Chicu” Reddy wrote his first poem when he was 5 or 6: an acrostic about Abraham Lincoln. “I think I still have it,” says Reddy, a professor in the Department of English Language and Literature. “I drew a little picture of Abe in the corner.” From that auspicious start, Reddy has gone on to write several works of poetry and criticism, including, most recently, the book-length poem Underworld Lit (Wave Books, 2020). In 2022 he was named poetry editor of the Paris Review; he also edits the Phoenix Poets book series for the University of Chicago Press. His comments have been edited and condensed.

Where did your interest in poetry begin?

I remember liking Shel Silverstein and the kinds of poems that many kids in this country grow up reading and hearing in school. In high school I had an amazing English teacher who had us read Walt Whitman and Wallace Stevens, and there was one poem by Stevens called “Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock”—it felt like time stopped.

So high school is when it started to feel like the art was speaking to me. That’s partly because of great teachers who knew that the wilder a poem was, the more exciting it would be to young people. They weren’t afraid to give us strange work—experimental poetry, modernist poetry—that isn’t often taught to students, back then or ever.

In college I started to write poetry, because there were classes with amazing poets like Lucie Brock-Broido, Seamus Heaney, and Louise Glück. That was the first time I got to be around poets and see they were real people who put on their socks in the morning and look a little tired in class and need to be driven to the grocery store when they’re visiting campus.

You’re both a poet and a scholar of poetry. Do the two ever feel in tension?

I think every poet thinks critically about poetry, if only to say, “This poem I just wrote is a piece of trash.” And the way you think about your work critically is by reading other poets and thinking about them critically. It’s always been a part of the art since the beginning. Ancient poetry is full of poems that are mocking other poets, praising other poets, thinking about other poets.

But it’s also sometimes been in tension with making, because you get an internal critic or editor in your head who can be very hard on you. And a lot of the time that goes into formal study and critical work can take away from the time you need to get to a place where you can write.

What does a poetry editor do?

They read a lot of poems. That’s the first thing you notice when you enter into this little world. I was knocked off balance by how much work crosses my desk every day. It’s like a fire hose. And reading poetry is a different kind of reading. It takes time and attention and care. So you can’t just swipe right or left—it’s not Tinder. I did have to learn how to read poems more quickly, and frankly, you do start to develop little personal algorithms. If the phrase “my mother” appears in the first line of a poem, my finger starts to swipe left. But I give it a chance!

I try not to automatically make those decisions, but you do start to be guided by your sense of what feels like exciting subject matter, exciting voices, exciting forms.

What considerations go into deciding what to publish?

The culture of the magazine matters. Poetry magazine, which I edited for three issues a year ago, has a lot more pages, and it’s devoted entirely to poetry, so we could take more risks on work that was interesting and weird. Whereas I’m finding now with Paris Review, we have maybe 20 pages of poetry an issue and still a huge number of submissions. I want to feel like every poem in the magazine stops me in my day, in my life, for a moment. It has to feel like something I haven’t seen before, and it has to have some emotional claim on me.

You’ve been at UChicago since 2003, since before creative writing was even a major. How has the culture around creative writing changed in that time?

It’s totally transformed. When I came here in 2003, I was a lecturer, not on the tenure line. My official title was the Moody Poet in Residence.

That feels pointed!

The lectureship was named after William Vaughn Moody, a poet who taught at the University in the 1890s. I wish I still had that title.

I thought I was here to hang out for a couple of years, teach a couple of courses, maybe write another book, and then move on. And now, creative writing is one of the largest majors in the humanities. We have more than a dozen writers teaching full time, we have a home in Taft House, an event series—all kinds of exciting things. Former students of mine are now creative writing professors all over the country.

Have you noticed changes in student writing?

When I arrived, UChicago was still the place where fun came to die. It was actually kind of a wonderful moment, because I had all of these punk nerds who geeked out on William Carlos Williams before they even walked into my classroom. They were making experimental films, they were all in bands, they were working at Cobb Café, they were pierced and angry about capitalism. They were such incredible writers—a lot of them have gone on to publish books of poetry and become real voices in the literary world.

As the College expanded, the character of the student body changed, and their work also changed. Students now are much more interested in social activism and how their work intersects with questions of social justice. I think the place of poetry and the work of poetry are viewed differently now, and that’s been exciting and challenging as a teacher.

If you could decree that every schoolchild in America had to memorize one poem, what poem would you pick?

It might be that Wallace Stevens poem, “Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock.” It’s funny and it’s colorful, and it’s about social conformity and the possibility of keeping wonder alive.

What’s your worst writing habit?

Lying down on the couch to write. I’m trying to write an adaptation of the ancient Indian epic the Mahabharata, which is one of the longest poems in existence. It’s about 10 times longer than the Iliad and the Odyssey put together. The only way I can deal with it is to lie flat on my back. I think it’s hilarious that I’m writing this ancient war epic while just chilling on my couch.

I think writers make little motors out of their bad habits that all come together and allow them to get the writing done. You always hear about Ernest Hemingway having to sharpen 20 pencils before he sat down to write. It’s compulsive but then, you know, For Whom the Bell Tolls happens. So.

What lines of poetry get stuck in your head?

There’s a beautiful line from George Herbert’s “Death.” He’s addressing death, who is, of course, a skeleton, and thinking about the resurrection, and he says, “And all thy bones with beautie shall be clad.” There’s something about that line that you just can’t help feeling is addressed to you.

And then there’s the opening of John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”: “Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness.”

That’s why I still think it’s important for students to read the poetry of the past, because it’s a resource that will come back to you when you’re on the Peloton or waiting on a canceled flight. There’s something about hearing “thou still unravish’d bride of quietness” in your head while you’re in Midway at Gate C, or whatever, that makes you feel like poetry is an art that is really mysterious and has a life across time that you would never imagine.

Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock

By Wallace Stevens

The houses are haunted

By white night-gowns.

None are green,

Or purple with green rings,

Or green with yellow rings,

Or yellow with blue rings.

None of them are strange,

With socks of lace

And beaded ceintures.

People are not going

To dream of baboons and periwinkles.

Only, here and there, an old sailor,

Drunk and asleep in his boots,

Catches tigers

In red weather.