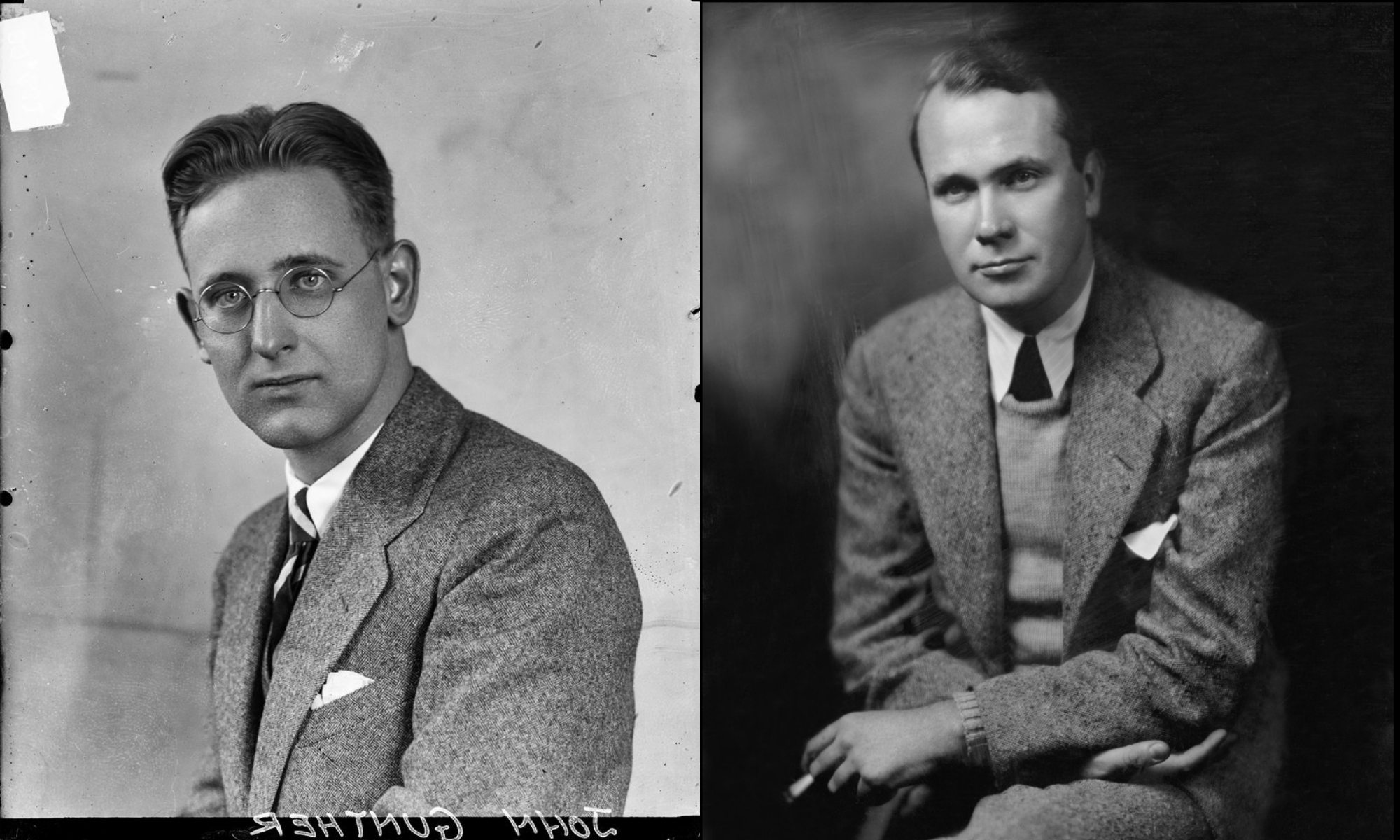

From left: Foreign correspondents John Gunther, PhB 1922, in 1926, and Vincent Sheean, EX 1921, in 1934. (From left: DN-0080461, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago Historical Society; Photography by Ben Pinchot [Vanity Fair, 1934], Condé Nast Collection/Artstor)

Reporters John Gunther, PhB 1922, and Vincent Sheean, EX 1921, sounded an early warning about the rise of European dictators.

One day, Hitler vowed, he would return to the Hotel Imperial. As a young man, he had shoveled snow in front of the grand Vienna hotel, doffing his cap respectfully at the Habsburgs, who ignored him. Underneath his obeisance was rage.

In the spring of 1938, after the German army marched into Austria, that day finally came. Hitler set up his headquarters in a first-floor suite—one floor up from the café that had been a favorite hangout of the era’s foreign correspondents.

That sharp shift of events inspired the title of Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took On a World at War (Random House, 2022), a new book by historian Deborah Cohen. Last Call is a group biography of a circle of foreign correspondents: Dorothy Thompson, H. R. Knickerbocker, Vincent Sheean, John Gunther, and Frances Fineman Gunther. Two members of this small circle—Sheean, EX 1921, and John Gunther, PhB 1922—began their illustrious careers at the Daily Maroon.

All household names in their day, this group of urbane foreign correspondents were friends and rivals. They drank heavily, threw raucous parties, had tumultuous marriages and affairs, and wrote brutally frank letters and diaries.

Middle-class Americans from provincial backgrounds, they understood what ordinary Americans wanted to know about the world, says Cohen. They also understood—and tried to convey to their readers—what the rise of dictators across Europe meant. War was inevitable, they all agreed; it was only a question of when.

Sheean, Gunther, and the others, with their portable typewriters and their unvarnished ambition, helped define the profession of foreign correspondent in the period between the two world wars. And they are almost entirely forgotten today.

In 2015 Cohen, a Northwestern professor who contributes to the Atlantic and other popular publications, drove down to Hyde Park to look at John Gunther’s files in Special Collections. Thinking she might write about Gunther’s taboo-breaking 1949 memoir Death Be Not Proud (Harper and Brothers), she wanted to read some of the thousands of letters he had received after its publication.

Gunther’s files in Special Collections fill up more than 300 boxes. He wrote 25 nonfiction books, seven novels, countless articles, drafts of novels and short stories that never made it into print, and reams of letters. On a whim, Cohen glanced through a 1937 folder marked “miscellaneous correspondence” and came across “incredible riches,” she says. There was a letter from Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehru describing his love for his late wife. A note from Czech foreign minister Jan Masaryk gossiping about the abdication crisis in Britain, calling it a “typically kinky British affair.”

The more she read, the more her scope broadened beyond Gunther. She realized he was part of a group of correspondents who shared a similar sensibility and career trajectory, and who had documented everything. “I’ve been a historian for 30 years and I’ve worked in some amazing archives,” Cohen said in an interview with the History Author Show, “but nothing like this.” The documents she unboxed revealed individual lives as well as a fateful stretch of world history.

By 1929 James Vincent Sheean, who used “Vincent Sheean” as his byline but went by “Jimmy,” had insinuated himself into a circle of writers and artists now known as the Bloomsbury Group. It was a remarkable achievement, given their reputation as “notoriously clubby and self-sustaining,” Cohen writes. Music critic Edward Sackville-West was one of Sheean’s lovers. (Eddy’s sister, Vita Sackville-West, was one of Virginia Woolf’s.)

This glamorous, bohemian existence was a world apart from Sheean’s hometown of Pana, Illinois, population 7,500. Sheean had plotted his escape for years. By high school he had read all of Shakespeare and learned French, Italian, and a bit of German; in his senior year, he wrote an essay on literature that won him a scholarship to UChicago.

At first Sheean struggled to fit into the byzantine social structure of the early University, which he pilloried in his 1935 memoir, Personal History. In a cringe-inducing anecdote, Sheean accepts a bid from a fraternity led by a Maroon editor he much admires. A woman student takes him aside to explain that pledging such a low-status fraternity would mean social death. Sheean, who has already moved into the fraternity house, climbs out the window in the middle of the night and flees.

John Gunther, a year behind Sheean, came from similarly humble beginnings on Chicago’s North Side. Formerly the Guenthers, the family changed their surname during the First World War. An ambitious autodidact like Sheean, Gunther kept a notebook of obscure vocabulary words and jotted down ideas, observations, and quotations on index cards. “Growing realization that I was meant for something big,” he noted on one of the cards.

Gunther enrolled in the College at age 17, living at home to save money. When he received bids from two fraternities, both considered “bad,” he turned them down, remaining a “barbarian,” as nonaffiliated men were called. Sheean and Gunther knew each other distantly, but Sheean—who later pledged a fraternity higher up the pecking order—considered Gunther “a real barb in those days.”

Sheean left UChicago without finishing his degree and moved to New York, where he was hired at the New York Daily News, the country’s first tabloid. In contrast, Gunther graduated in 1922 and began his journalism career as a cub reporter at the Chicago Daily News, considered the most literary of Chicago’s newspapers.

By the mid-1920s both had landed in Europe—Sheean went first to Paris, Gunther to London—and were busily reinventing themselves as foreign correspondents. Scoops, they learned, were to be sent by cable. Less urgent stories, called “mailers,” were longer, more colorful articles sent by post, which was cheaper.

Gunther had managed to get his first scoop on the journey to England: Edward, the Prince of Wales, was traveling on the same ship from New York to Southampton. Gunther got a $100 advance from the United Press to move to first class, the better to stalk his prey.

While much of the correspondents’ reporting centered on Europe, they occasionally traveled farther afield. In 1925 Sheean went to Morocco to cover the Rif War, a rebellion against the Spanish. He was determined to interview the leader of the Rifi, Mohammed ben Abd el-Krim, who had established an Islamic republic in hopes of uniting Muslims against European imperialism. To get past the Spanish blockade, Sheean wore traditional North African clothing and rode a mule across rugged terrain. He got his interview—and a reputation for going to extreme lengths to nab a story.

In 1929 Sheean and Gunther were both reporting from Palestine, a former Ottoman territory that the League of Nations had given to the British to administer after World War I. Sheean filed some of the earliest reports of the outbreak of violence between Arabs and Jews, which began at the Western (or Wailing) Wall and left hundreds dead. Hard-bitten Sheean was so shaken by what he saw that he had a nervous breakdown.

Gunther, arriving later, wrote a series of mailers attempting to explain the complexity of the conflict, which had inflamed international opinion: “a question with no solution,” he wrote. During these dark times in Jerusalem, Sheean and Gunther finally became friends.

Back in Europe, the political situation showed similar signs of instability and impending violence. “Armed with a peculiarly American obsession with personalities,” Cohen writes, this group of correspondents “sounded an early warning about the rise of the dictators.” As early as 1926, Gunther had the idea for a series of articles about countries that had become dictatorships: Poland, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and on and on.

Objectivity had become a journalistic ideal in the 1920s, just as Gunther and the others were beginning their careers abroad. But as the situation in Europe deteriorated, they began to question this approach.

By the early 1930s, Gunther had settled in Vienna with his wife, Frances—then a correspondent for the London News Chronicle—and their son, Johnny. When the Nazis came to power in Germany, Gunther tried to write about their terror campaign against the Jews. Gunther’s Chicago editor, firmly believing there must be two sides to any dispute, requested “more diversified” articles, since the purpose of a newspaper “is to publish a well-rounded account of events.”

Sheean filed similar dispatches about the persecution of Jews in Austria after its annexation—worse than in Germany, he reported. He even predicted the Nazis would try to murder all of Europe’s Jews, “and the rest of the population—terrified, half believing, uncertain—will be glad to forget it in a week or so and say it was ‘all greatly exaggerated by the foreign press,’” he complained bitterly.

In 1936 Gunther finally had the chance to make his case about the rise of dictatorships—all 500-plus pages of it. His book Inside Europe (Harper and Brothers) focused primarily on the new crop of dictators—Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin—and the diplomats who seemed powerless to keep them in check. “Unresolved personal conflicts in the lives of various European politicians may contribute to the collapse of our civilization,” Gunther asserted, echoing the Freudian thinking that was fashionable at the time. (John and Frances Gunther had both undergone psychoanalysis in Vienna with an acolyte of Freud.)

Sheean agreed with Gunther’s focus on the rise of individual personalities but rejected his Freudian analysis. He struggled to provide a blurb for his friend’s book. “You may not agree with Gunther’s central thesis on the historic role of the accidents of personality (I don’t, for instance),” he wrote in an early draft.

Immediately banned in Germany (a fact the publisher played up), Inside Europe sold a million copies worldwide. Anthony Eden, British foreign secretary and future prime minister, was observed reading it; young John F. Kennedy took a copy with him when he traveled to Europe. The book became the first installment of a series of best-selling books for Gunther: Inside Asia (1939), Inside U.S.A. (1947), Inside Africa (1955), Inside South America (1967), and more.

Like Gunther, in Last Call at the Hotel Imperial Cohen juxtaposes the personal with the political (to the point of distraction, some reviewers have suggested). Sheean, Gunther, and the others—as revealed by their letters and diaries—come across as deeply flawed characters, lurching from one personal disaster to the next.

Sheean and Gunther revealed a little of their private lives themselves, in memoirs that were, at the time, considered outré. Published in 1935, Sheean’s Personal History was a literary sensation: “the coming-of-age memoir of the 1930s,” in Cohen’s description. Not quite an autobiography, it was the story of a young man trying to find his place in a new and confusing world. The success of the book—in which names were left unchanged—made him feel “like a dog that’s made a mess in the middle of the drawing room,” Sheean wrote to Eddy Sackville-West. “I couldn’t help making the mess, but now I feel very guilty and very conspicuous.” The book was the inspiration for the 1940 Alfred Hitchcock film Foreign Correspondent.

Gunther’s memoir came later, in 1949, after his son Johnny died of brain cancer at age 17. Death Be Not Proud—the title taken from a sonnet by John Donne—was a slim volume in three parts: Gunther’s narrative of his son’s illness, excerpts from Johnny’s writings, and an afterword by Frances Gunther, by then his ex-wife.

“To air publicly such an intimate story of sickness and suffering was unheard of,” Cohen writes. Some reviewers were shocked, but letters from bereaved parents poured in: Gunther had finally spoken the grief in their hearts. It was this collection of letters, now in Special Collections, that Cohen had first wanted to peek at.

In their later careers, Gunther and the others wrote numerous best sellers and Book-of-the-Month Club selections. Sheean wrote a tell-all book about a marriage that wasn’t his—Dorothy and Red (Houghton Mifflin, 1963), on fellow foreign correspondent Dorothy Thompson and her second husband, author Sinclair “Red” Lewis. “Vincent Sheean uses all his fine skill as a war correspondent to dramatize the embattled marriage,” read one review.

But of all these widely read, commercially successful books, Death Be Not Proud is the only one still in print.

According to the “great man” theory of history, Hitler himself, through the force of his charismatic, sociopathic personality, brought about Naziism. No Hitler: no Nazis, no Holocaust.

In the 1930s, when Gunther, Sheean, and the others pointed to dictators who were driving the world to war, says Cohen, “they’re resuscitating a 19th-century idea,” developed around the time of Napoleon, “that history depends on great men.” This group of foreign correspondents “became very focused on these personalities. And that causes a big rush to try to land interviews with them.”

Hitler, by all accounts, was a terrible interview; rather than answering questions, he delivered his usual speeches to an audience of one. Gunther, in an attempt to comprehend him through his upbringing (Freud again), traveled to rural Austria and interviewed his peasant relatives.

After World War II, “historians turned away from these ideas,” says Cohen, and “disdained the great man theory.” The postwar approach, focusing on larger swaths of society, was possible partly because more facts became available, she says. The Nazis, for example, closely monitored public opinion. These archives were accessible for study after the war—a luxury not available to reporters of the time, when freedom of the press was curtailed. (Desperate to learn the views of ordinary Germans, Gunther resorted to going to the movies; when Hitler came onscreen, he noted how many people applauded and how enthusiastically. It wasn’t much to go on.)

But in the last decade, with the rise of “new model authoritarianism” around the world, some scholars are reexamining their assumptions, Cohen says. She noticed the shift even as she worked on Last Call at the Hotel Imperial. She began her research in 2015; Donald Trump was elected in 2016.

In 2017 Princeton historian David Bell published the essay “Donald Trump Is Making the Great Man Theory of History Great Again” in Foreign Policy. He argued that Trump—whether you supported him or not—is exceptional in American history. To understand his presidency, historians need different tools. “We’re in a phase,” says Cohen, “when the great man reporting these correspondents did in the 1930s seems exigent.”

Updated 09.09.2022: Corrected to reflect the full extent of Special Collections’ records on John Gunther.