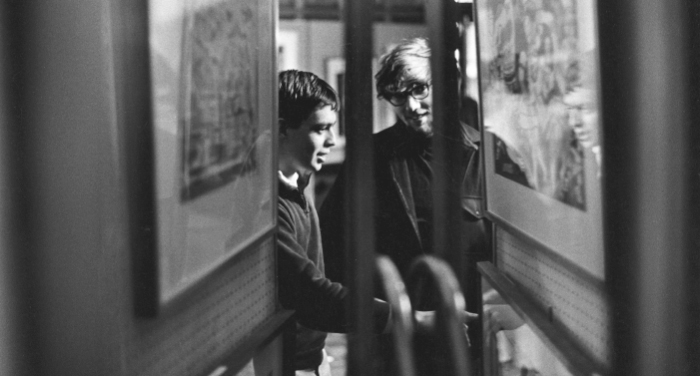

First-year Michael Burke waited in line at the Smart Museum for about six hours in hopes of taking home a piece of art. “I’m so excited to hang this,” he said after selecting Alfred Leslie’s Four Women (1964). Getting to spend a year living with the print was “totally worth the wait.” (Photography by Eddie Quinones)

After a decades-long hiatus, Art to Live With is back.

In 1968 University of Chicago students camped out overnight in Ida Noyes Hall for the chance to take home works by artists including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and René Magritte. The prints and paintings were theirs to display in their rooms and enjoy for the rest of the quarter

This fall a new generation of students showed equal commitment when the Art to Live With program returned after a three-decade hiatus. By 8 a.m. on the day of Art Match, the courtyard outside the Smart Museum was filled with around 100 students, some of whom had arrived as early as 11 p.m., and strewn with backpacks, sleeping bags, blankets, and a touch of Warhol whimsy in the form of a giant stuffed Winnie the Pooh.

The program was founded in 1958 by dean of students Harold Haydon, LAB’26, PhB’30, AM’31, and Joseph R. Shapiro, EX’34, an art collector and a cofounder of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Shapiro believed “the best way to become acquainted with art—and to appreciate it—is to live with it.” So he tried to give students the experience he had every day as a collector. By 1962 the number of works available for students to borrow had grown from 50 to 500. (Although the pieces were originally on loan, Shapiro later donated them to the University.) The collection included several works by contemporary Chicago artists that Shapiro hoped would appeal to students’ tastes.

Judging by the hours-long campouts, he succeeded. Some pieces were especially hot property, sparking multiyear quests. In 1978 graduate student Leo Maulen, AM’76, AM’81, AM’97, was first in line and determined not to repeat the experience he’d had in previous years. “I never got the painting I wanted,” he told the Magazine that year. “It was always snatched before my very eyes.”

Although the program enjoyed huge popularity in the 1960s and ’70s, Art to Live With was discontinued in the late 1980s. (Some of the original pieces now hang in public spaces around campus; others will be available to borrow in years to come.) The program’s return was made possible by a gift from University trustee Gregory Wendt, AB’83, who participated as a student, borrowing a print by the Latvian American artist Sven Lukin.

This year prints by Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró are especially coveted, says first-year Michael Burke (pictured at the top of the page), who arrived at the Smart Museum around 1:45 a.m. and by sunup is “running on the free coffee that they gave us.” Burke has his eyes on the abstract, brightly colored works of the 20th-century American painter Alfred Jensen. “I don’t think the Picasso is that cute, actually,” he says. “I more want something that I want to look at every day.” But he’d be happy with anything. (In the end he leaves with Alfred Leslie’s Four Women, which, with its 1960s look, “is totally giving me Dreamgirls vibes.”)

Behind Burke in line, fellow first-year Will Asness is hoping for a Miró, though he’s realistic about his chances of getting one (slim) and cheerful despite how long he’s been awake (nearly 24 hours). It hasn’t been the night he planned: “I was walking back to my dorm to get a nice, nice sleep” when a friend told him everyone was camping out to get art. It sounded like a fun way to spend the night, and besides, he’s got a “section of free wall just calling for” something to fill it.

In groups of six or seven, students are let into the museum to pick from the 75 pieces on offer. Once they’ve made a selection, they fill out some paperwork and wait for their art to be bubble wrapped for safe transportation to its new exhibition space. Today the program is entirely free, but in its first iteration, students paid a fee of 50 cents to a dollar to secure the loan.

Despite what you might imagine, museum staff aren’t too concerned about the safety of the objects back in the residence halls. It’s a bit like taking home the class hamster, explains Alison Gass, the Dana Feitler Director of the Smart Museum. “I’ve talked with other museum directors, because there are strong programs like this across the country, … and what everybody tells me is that it’s actually quite amazing how respectful and responsible students are toward these art objects. Very rarely does real damage happen to them.” (The museums are also careful about which pieces they lend. The Picassos and Mirós in the Art to Live With collection are prints—still valuable, and touched by the artists’ hands—and no one, Gass says with a laugh, is getting the museum’s beloved Rothko.)

First-year Alex LaHood admits he’s feeling the pressure: the thought of living with a piece of art history is “slightly stressful but also cool.” His housemate Ethan Truelove is equally incredulous that the Francisco de Goya print he selected will be sitting next to “a six-dollar nylon flag and some baseball caps I have on my wall, and the little University of Chicago felt flag that everyone else has.”

As the line progresses, fewer and fewer students end up with their first choices, but most take the setback in stride. First-year Julia Matyjas picked a tropical landscape print by Georges Rouault (see below) that complements her room’s travel-themed décor; her roommate wound up with Francis Chapin’s sketch of a figure sitting on a stool, which she deems “the most normal one left.” Third-year Ben Warren selects a piece he and his friends have dubbed “the Creepy Baby” (actual title: Baby with Blue Scarf by Eleanor Coen). “This guy liked it,” he explains, gesturing to his roommate. “I can vibe with it,” the roommate agrees.

Gass says that students will soon play a bigger role in selecting the pieces included in Art to Live With. The Smart plans to put together a student collections committee, similar to the museum board’s collections committee. With the students’ help, Gass hopes they can diversify the works available to borrow, “so that we have artists from every background represented.”

And with more pieces in the collection, more students will have the opportunity to live with art. Outside the Smart Museum, a late arrival sounds wistful as she admires her friend’s choice. “I’ll go to your room all the time and stand there and bask.”