(Photography by Pierre Tourigny, CC BY 2.0)

Face-off

Looking good? Nicholas Epley’s study suggests you look again.

Nicholas Epley, John T. Keller professor of behavioral science and John E. Jeuck faculty fellow at the Chicago Booth, found his work thrust into the spotlight recently when a Scientific American article titled “You Are Less Beautiful Than You Think” cited a 2008 study by Epley and Erin Whitchurch from the University of Virginia.

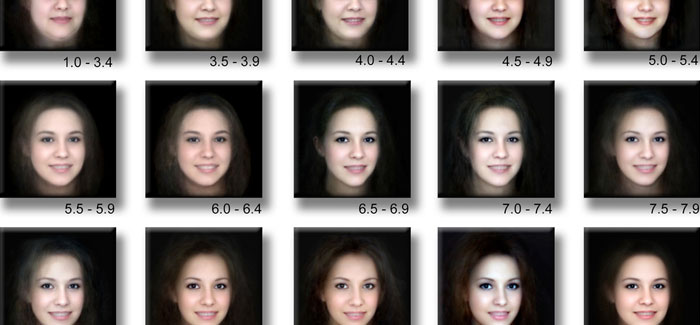

In that study, “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Enhancement in Self-Recognition,” published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Epley and Whitchurch posited that humans see ourselves as better looking than we actually are, an idea that contradicts the popular ad campaign “Dove Real Beauty Sketches.”

Curious to know why he created such a potentially deflating experiment, I asked Epley about the study shortly before uploading some flattering photos of myself to Facebook.

What inspired your original study?

I wish I could say it was some really interesting moment in my life, but it was actually a long-running empirical question in the field of psychology. In many different ways, researchers have documented interesting tendencies for self-enhancement: people (especially Westerners) tending to think that they are in some way “better” than they actually are. These findings are almost always hampered, however, by an inability to get an objective measure of reality that you can compare people’s judgments against. If a man says he is an above average driver or teacher or leader, how do you know whether that assessment is actually right or wrong? Psychologists have identified many clever ways to answer that question, but we thought the simplest way was to find the most objective measure of a person that we could think of. That measure was your actual physical image. And so, this allowed us what we thought was a relatively clear and objective measure of self-enhancement: would our participants think their physical image was more attractive than it actually was?

What are the practical applications of your study’s results?

The most practical lesson one can learn from findings like these in psychology, I think, is a lesson in humility. We are members of one of the most brilliant species our planet has ever seen. Our brains are remarkable in so many ways. And yet, our brains are also prone to overconfidence, leading us to think we know much more about ourselves and others than we actually do. Obtaining an accurate view of the world—both of yourself and others around you—requires and understanding that there might be more to the world than your intuitions and common sense suggest. I think there is nothing so practical as this lesson in humility. I think all of my research, in one way or another, teaches this lesson in different ways over and over again.

It’s hard not to think, looking over the paper, that the study looked rather fun. What were the most enjoyable parts of setting up the experiments?

Two things in particular were the most fun. First, morphing ourselves. Erin and I had great fun experiencing the experiment from the participants’ viewpoints. I felt our effect very clearly. Second, morphing the face of one of our particularly memorable research assistants for one of the studies. Although this research assistant was one my favorite undergraduates I ever worked with, our participants did not enhance his image in their memory.

How were you alerted to Scientific American referencing your paper as contradiction to the Dove ads?

Out of the blue a few days ago I got an invitation to give a public lecture, and the invitation mentioned this research being described in Scientific American. And then, just shortly after that, I saw the article posted in the hallway of our building. I never saw it before then.

What are you working on now?

I’m just finishing up a book describing how, and how well, we understand both ourselves and others. It’s called Mindwise. Its main focus is really on the many different ways we misunderstand each other, the predictable mistakes those misunderstandings create, and what we can do to understand ourselves and others better. I think it’s a 200-page lesson in the virtues of humility, dialogue, and social connection.