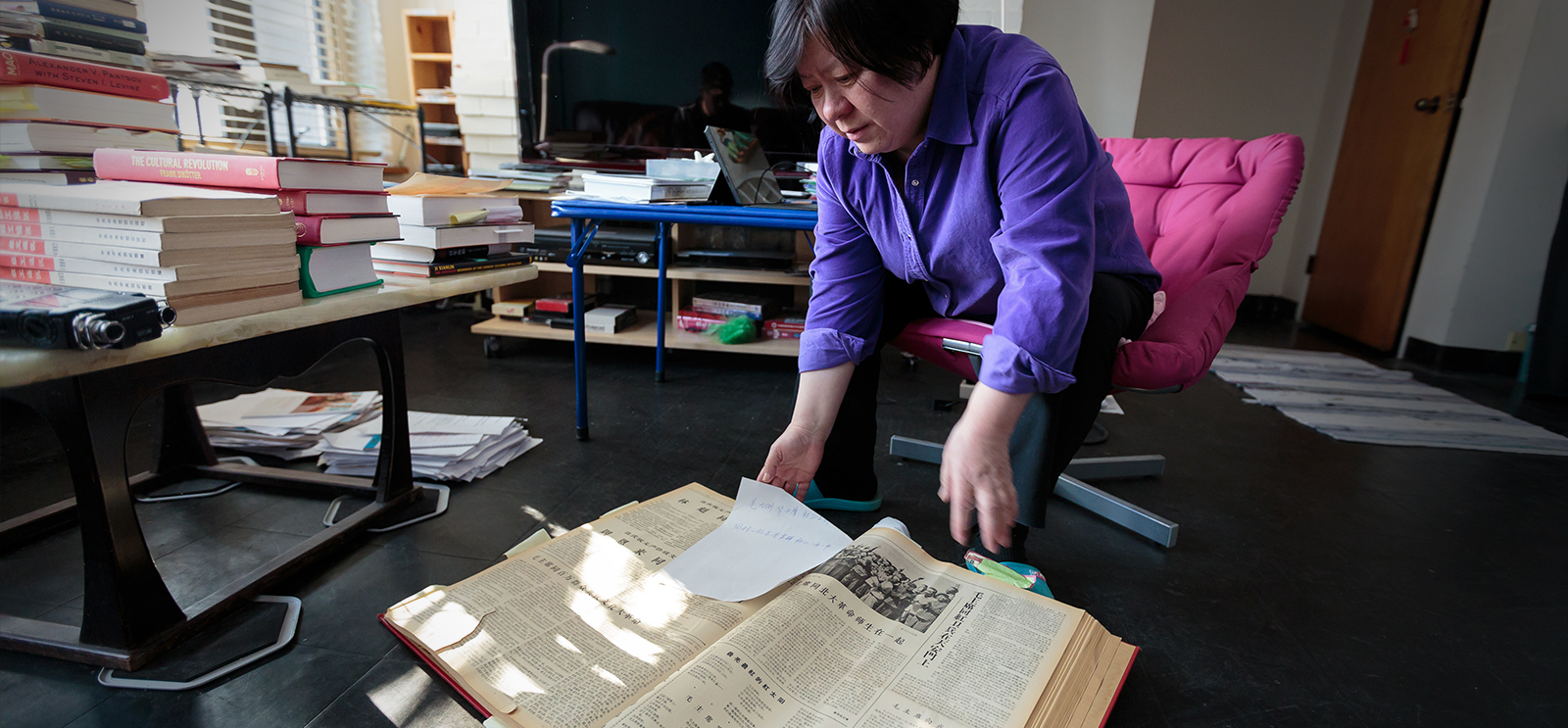

Wang’s home is filled with artifacts of her quest to memorialize the dead. (Photography by John Zich)

Youqin Wang refuses to let the victims of China’s Cultural Revolution be forgotten.

Youqin Wang was 13 years old when her fellow classmates beat her middle school vice principal, Bian Zhongyun, to death.

The events of August 5, 1966, hadn’t begun so violently. “They just poured ink on the [vice] principal’s head,” recalls Wang. But over the course of the afternoon, she watched as students at the girls’ middle school attached to Beijing Teachers University traded in the ink for boiling water and took up clubs spiked with nails. When the administrator fell unconscious, students threw her body into a garbage cart.

Wang doesn’t flinch when she remembers that day. Now a senior lecturer in Chinese language at UChicago, she repeats the graphic details of Bian’s death often—not for the shock value, but because few others will. For almost 40 years, Wang has been on a solitary mission to gather and tell the stories of the individuals who lost their lives during China’s Cultural Revolution. It’s not known exactly how many people died, but estimates range from 500,000 to several million.

In 2004 Wang published a book listing the details of 659 deaths from the Cultural Revolution, and she maintains a website listing nearly 200 more. It’s a painstaking effort. Records from those years are scattered far and wide, and while a handful of the people who participated in the violence have apologized, the Chinese government has done little to preserve the memory of the deceased.

Yet Wang can’t be deterred. “Someone should tell people the truth,” she says quietly.

The Cultural Revolution began three months before Bian’s death, when Mao Zedong first enlisted students across the country to persecute perceived enemies of his Communist Party. Over the next three years, the youths captured, tortured, and killed suspected counterrevolutionaries, particularly urban intellectuals like Bian.

Those victims’ stories line Wang’s sunny Hyde Park apartment. Binders stuffed with interview notes fill long rows of shelves, while stacks of neatly labeled plastic tubs house reams of photocopies. As she talks, Wang moves from room to room looking for documents. Not that she needs them—Wang seems to effortlessly recall intimate details of each case she mentions: the department where he worked, how she was publicly humiliated, the way they committed suicide together after years of persecution.

Wang was a bright student, skipping several grades in elementary school. But during the Cultural Revolution, Mao suspended the formal education system, instead sending urban youth to work in the Chinese countryside. So, in 1969, Wang went not to a university, but to the rural province of Yunnan, where she spent six backbreaking years clearing bamboo and planting rubber trees. While there, Wang found a tattered journal of world literature containing an excerpt of Anne Frank’s diary, which inspired her to begin documenting the injustices she had encountered herself.

As she wrote in one of her notebooks: “Even though I cannot change anything that is happening, at least I can record them.”

Following Mao’s death in 1976, college entrance exams resumed and Wang enrolled at Beijing University. In her free time, she visited old classmates to ask about their experiences during the Revolution. In the late ’80s, Wang started more methodically tracking down family members of the victims.

In 1995 she published a report documenting 63 individuals from Beijing University who died during the Cultural Revolution. But her list kept growing. When she arrived at UChicago in 1999, she created a website to house the memorial. Today the site lists 755 names and descriptions of another 70 unidentified victims, from all across China.

They have a way of haunting her—like physicist YuTai Rao, SB 1917, who was imprisoned on his Beijing campus. He escaped one night, returned home, and hanged himself. “He even didn’t have time to get a rope,” says Wang. “He just found a piece of fabric.”

To date Wang has uncovered 13 individuals who, like Rao, graduated from UChicago and later died or committed suicide as part of the Cultural Revolution. It’s a vivid reminder that the past, however painful it may be, has a distinct place in the present—the same lesson she seems determined to impart to others.

On her website, Wang shares a story from a man sentenced to farm labor during the Cultural Revolution. One day a cow from his herd was slaughtered under a willow tree. From then on, the other cows refused to go near the tree. By contrast, the chickens strutted happily where their friends had been butchered. The chickens forgot, but the cows remembered. Wang remembers too.