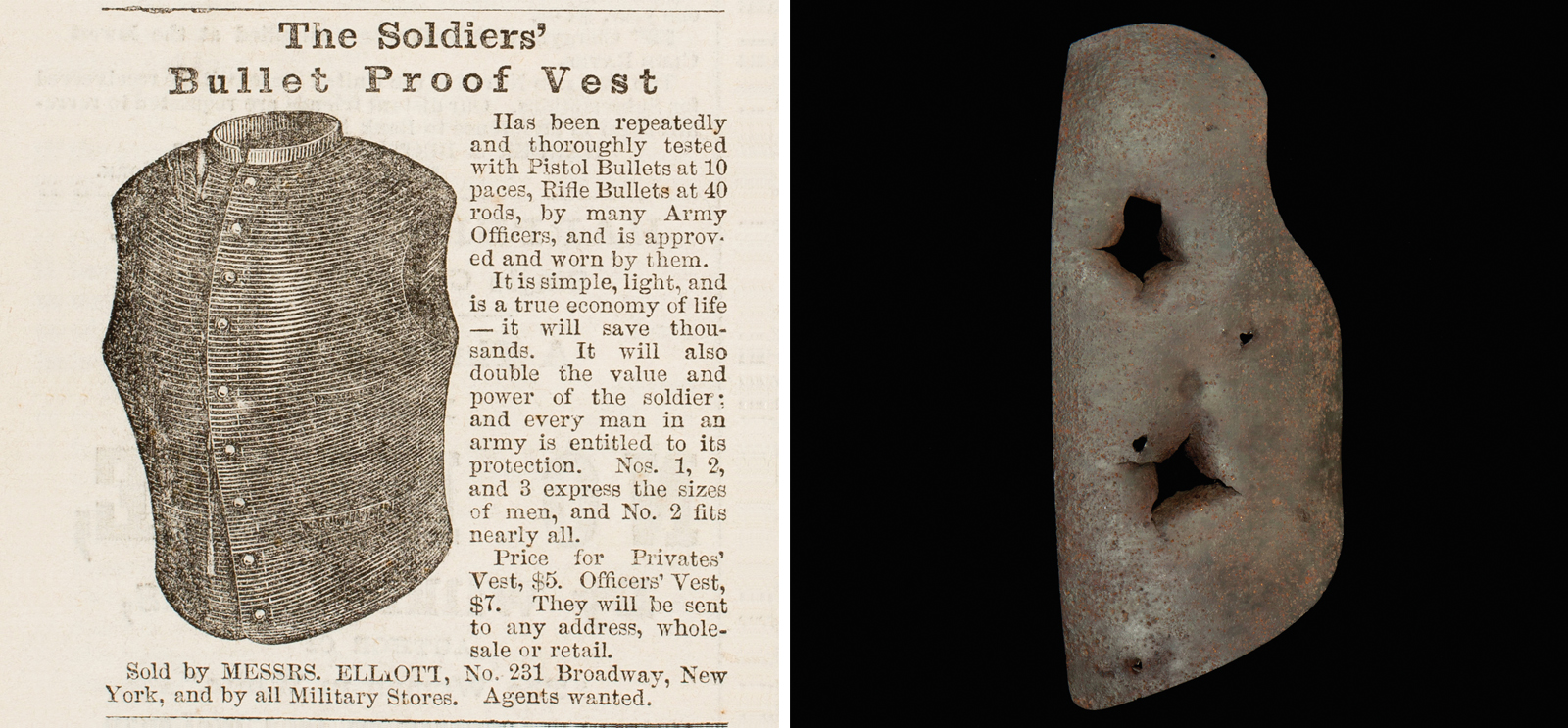

An 1862 ad for a bulletproof vest in Harper’s Weekly (left) promises to “double the value and power of the soldier,” while the breastplate of such a vest, found on a Shiloh battlefield, reveals its penetrability. (Photos courtesy American Antiquarian Society, Worchester, Massachusetts (left), and Tennessee Virtual Archive, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville)

The clothing and material culture of the Civil War era offer a history student new insights into gender and race.

What can a bulletproof vest tell us about gender? How can one’s choice of clothing reveal racial discrimination in America? Doctoral student Sarah Jones Weicksel, AM’09 (History), uses clothing, images, texts, and other objects to understand gender, race, material culture, and everyday life during the Civil War and emancipation.

As part of a Committee on Institutional Cooperation/Smithsonian Institution fellowship, Weicksel is researching materials at the National Museums of American History and African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. The objects—some newly donated—help her answer such questions for her dissertation, “The Fabric of War: Clothing, Culture, and Violence in the American Civil War Era.”

What objects have you found surprising or out of the ordinary?

One of the most entertaining was a pair of pants worn by a Union Zouave soldier (see cover). They’re basically 1860s Hammer pants. You see them in photographs and illustrations, but looking at them in front of you gives you a different understanding of how they would actually fit, how baggy and loose, and how vibrant the colors were.

Probably the most surprising thing—and this wasn’t at the Smithsonian but in my broader research—was how many bulletproof vests exist. I have a chapter in a volume coming out in May that looks at body armor, death, and gender in the Civil War.

What do these vests have to do with gender?

Historians have assumed that men who wore them were considered cowardly by their comrades, but there’s a more complex story. With body armor, we see two competing ideals of manhood and duty—one that demanded that a soldier sacrifice his life for the nation and another that valued the protection of his life.

Advertisers helped Americans view using armor as a manly act. To confront the enemy was brave, but to protect oneself showed that a man had a stronger sense of manhood and commitment to both nation and family. This was a shifting culture in which death and manhood were intertwined.

Unfortunately, the vests were incredibly dangerous. You’re basically wearing a fabric vest that encases a thin steel shell. If you were shot at from close range, you would have had a bullet, cloth, and shrapnel pushed into the wound.

What can clothing tell you that text or photography can’t?

If I rely solely on texts, I can tell one kind of story, but if I place those texts in conversation with images and material culture, I have a different story. In the case of body armor, texts reveal how much the vests cost, available sizes, and men’s thoughts about them. When I add the actual objects, I get a real sense of their size, of how jagged the edges are when punctured. That knowledge allows me to read the texts differently.

What objects do you see a lot of? What is missing?

I see so many uniforms. Lots of photographs, lots of items related to generals. What’s missing is clothing worn by poor or enslaved people. If you only have a few outfits, you wear them until they’re falling apart.

How is your research reflected in contemporary culture?

The powerful role clothing played in the 1860s and ’70s helped frame today’s attitudes about clothing and race. African Americans expressing themselves through clothing experienced a violent backlash in the postwar era. Incidents related to clothing in which white men and women targeted African Americans—whether stripping it off of a person’s body or being upset about a black woman wearing a fine dress—could be precursors to a horrific assault or even a lynching.

Wearing clothing that did not fit white society’s dress codes could be considered a defiant act that could prompt physical violence, which was then, and continues to be, blamed on the victims. For many, evoking the image of the hoodie recalls the death of Trayvon Martin. It’s important that we understand clothing’s place in emancipation—that’s one defining moment that continues to shape the way people think about self-presentation in relationship to race.

How does your research fit into Civil War research as a whole?

The Civil War is one of the most studied topics in US history. So you might ask what could be left to say. But there has only recently been an effort to think about the material culture of this war. By weaving together objects, images, and texts, I tell a different kind of history about everyday wartime conflicts—how people created new boundaries of belonging and exclusion. Through clothing, people confronted questions about race, gender, the individual, and their relationships to one another and the government. Those struggles helped to determine who, on what terms and by whose authority, would be considered “American.”

Interview edited and adapted.