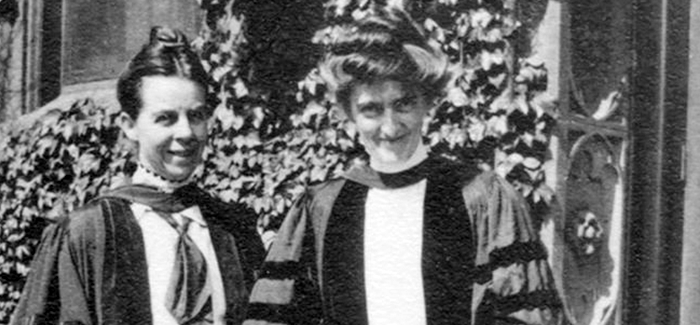

Marion Talbot and Sophonisba Breckinridge, PhM 1897, PhD 1901, JD 1904, stand on the steps of Green Hall following the convocation ceremony in June 1909. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-02249, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

A Center for Gender and Sexuality Studies event explores a lesbian love triangle dating to UChicago’s earliest days.

One of my memories is little Miss Breckinridge, trudging along on a cold winter night over a few blocks to see Miss Talbot. She went every night to see her. On the other hand, Miss Talbot and Miss Abbott were not friends. I don’t know what the cause was. But at any rate, Miss Breckinridge loved both of them.—A former University of Chicago student

Crowds of people filled the Center for Gender and Sexuality Studies last month for an event titled “A Lesbian Love Triangle at the University of Chicago: Sophonisba Breckinridge, Marion Talbot, and Edith Abbott.” I saw an entire row of chairs occupied by Breckies, current residents of Breckinridge Hall, who came to learn about the history behind the name on their dorm. Anya Jabour, professor of history and codirector of the Program in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Montana, is writing the first biography of activist and political science professor Sophonisba Breckinridge, PhM 1897, PhD 1901, JD 1904. Jabour’s research suggests intimate personal and professional relationships between Breckenridge and Marion Talbot, who was once dean of women at UChicago, as well as with Edith Abbott, who was the dean of the School of Social Service Administration.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2339","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"576","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Sophonisba Breckinridge, undated. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-02238, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2342","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Marion Talbot, 1895. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-04447, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2341","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"576","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Edith Abbott, 1919. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-00003, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

According to Jabour, Breckenridge’s relationship with Talbot began in 1894, while Breckinridge was visiting a friend in Chicago. Talbot encouraged Breckinridge to pursue graduate study at UChicago, helping her finance her program with a graduate fellowship and a position as Talbot’s personal assistant. By 1899, they each lived in Green Hall, where Talbot insisted that her study have an adjoining door to Breckinridge’s, so that they shared a suite. They vacationed together and were each other’s closest companions.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2346","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Breckinridge’s quarters in Green Hall, 1940. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-02233, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

That is, until Edith Abbott arrived in 1905. Breckinridge was Abbott’s instructor in the Legal and Economic Position of Women, what is arguably the first women’s studies course in the United States. According to Jabour, “By 1911 it was clear that Talbot felt threatened by Abbott personally and professionally.” Abbott eventually supplanted Talbot as Breckinridge’s closest companion, although Jabour states the two “seemed to be locked in a battle to prove who loved Breckinridge most.” The most interesting evidence of this dispute came from letters that Talbot and Abbott exchanged during that time. Talbot was offended by something that Abbott had done (unspecified in the letters), yet she tried to make peace with Abbott for Breckinridge’s sake.

I do [seek reconciliation], that I may be guided in my method for helping make Nisba’s life as happy and enriched as it is in my power to do. An aim that has been constantly before me since the day when she came to me, and let me lift her out from the shadow into the light, seventeen years ago.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2345","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Abbott, 1936. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-00023, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Jabour states that Abbott’s response “simultaneously acknowledged Talbot’s years of support and downgraded their number.”

Of course I do not need to be reminded of the help you gave Nisba 14 years ago! She will never leave one to forget any kindness that has been hers. The thing she forgets, of course, is that no one ever had the blessed privilege of doing anything for her who has not been paid over and over a thousand times full measure and been left in her debt.

I feel quite unable to tell you how ashamed I am of the blunders I seem to have made. It seems very hard, when I think I see what it has meant to have the joy of knowing and loving her. Of trying to see how full of beauty she is, with so much room for life and loving. It seems very hard that I should waste any of her precious friends.

I can only say again that if I have been rude to you or to anyone she loves, I have not meant to be, and I am ashamed of myself if I have so blundered, as I heartily apologize.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2343","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Talbot, undated. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-01392, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Talbot eventually accepted second place, and (because Talbot made generous donations to the SSA, where Abbott was dean) Abbott made an effort to be cordial. Abbott and Breckinridge spent most of their time together and eventually moved in together in 1940. Yet despite their complex personal relationships, these three women worked together to support women’s rights in academia for 40 years. Talbot created a fellowship in Breckinridge’s name, and her insistence that women with doctorates and publications be promoted to full professorships resulted in promotions for both Breckinridge and Abbott. But the complicated question persists: were they lesbians? Not in our traditional sense. Talbot, Breckinridge, and Abbott lived on the brink of an era when society was only starting to believe that women possessed any sexual feelings at all. According to Jabour, as little ladies merging out of the Victorian era, they would not even remotely consider themselves part of the queer subculture that was emerging in Chicago.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"2344","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Breckinridge (left) and Abbott, undated. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-00008, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

According to Jabour, Breckinridge recognized in her letters that heterosexual marriages were the cultural norm, but there is also evidence that “Boston marriages” between women academics were common, helping those women to further their careers. While Breckinridge and Abbott never discussed a physical relationship in their letters, there is certainly evidence for an emotional one. On a mere 10-day vacation, Breckenridge would write to Abbott daily or twice daily. Some excerpts from the letters from one vacation:

You are very constantly in my mind, it seems a long time until next Friday.

I miss you terribly. It is wonderful to look forward to being with you again.

I really cannot stand much more of this. It is all so huge, and the distances are so great, and we are so far away from one another.

Edith, when you get back, and I get back, don’t let me go again. I can’t get along without you.

Have I said that I have made up my mind? That once you got back and I got back myself I would never let you out of my sight again? And I’d ask you never to let me go away.

Breckinridge repeated this message through letters to Abbott three more times over the last two days of their vacation. There was no evidence of them ever separating again, until Breckinridge’s death, where Abbott was the primary beneficiary in her will.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"2340","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"453","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Breckinridge and Talbot, undated. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-02248, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

I was drawn to the talk to hear a scandal, but instead I heard a story of incredible passion, both for the activists’ professional work and for their personal relationships. The talk was a part of Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles: A History of LGBTQ Life at the University of Chicago, an oral history project that culminates in a Special Collections Research Center exhibit scheduled for this spring, March 30–June 12, 2015.