In his new book, Theodore Jun Yoo, AM’97, PhD’02, used the thriller Burning, pictured here, to illustrate the economic anxiety of young Koreans. (Image courtesy Well Go USA)

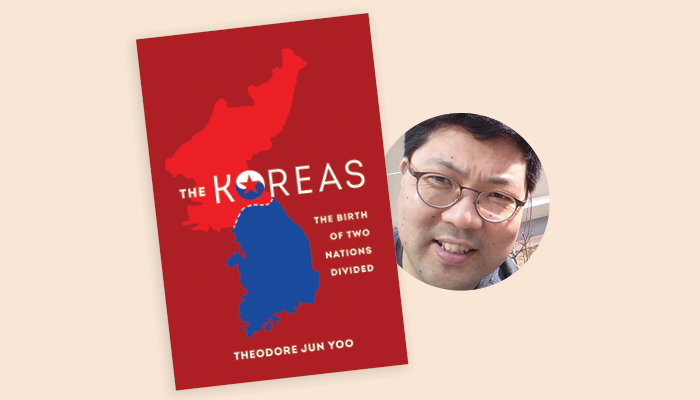

Theodore Jun Yoo's (AM’97, PhD’02) new history of the Koreas unites academic and personal interests.

“If you read my first book and get to know me personally,” says historian Theodore Jun Yoo, “you’ll realize a lot of it is my mother talking to me.”

After writing his first two books, The Politics of Gender in Colonial Korea: Education, Labor, and Health, 1910–1945 (University of California Press, 2014) and It’s Madness: The Politics of Mental Health in Colonial Korea (University of California Press, 2016), Yoo AM’97, PhD’02, realized that as much as they were academic endeavors they were also attempts to understand his mother’s anger—and its roots in Japanese occupation, poverty, political persecution, and a cultural reluctance to talk about emotions.

Yoo’s third book, The Koreas: The Birth of Two Nations Divided (University of California Press, 2020), continues the work of trying to understand the country of his birth and current residence, and the ways it shaped him and his family. The book takes a decade-by-decade look at North and South Korea—“twins born of the Cold War”—since they separated in 1948. In situating both countries in time, Yoo also situates them in place, mapping out global connections and tracing the Korean diaspora—emigrants and immigrants, across the globe, to and from Germany, Vietnam, Ethiopia, the United States, and elsewhere.

Born in Seoul to parents who left the north during the Korean War, Yoo became part of that diaspora at three when his father signed up as a government dispatch doctor in Ethiopia, where Yoo grew up. Like many Korean immigrants of their generation, he says, his parents shared little of their feelings about their childhoods or home country, leaving him to turn to academia as a way of understanding where he came from.

So one of the primary audiences Yoo had in mind writing The Koreas was people like him. “For us,” he says, “I think it’s so important to understand the reasons why our parents left.”

At the same time, Yoo wanted to give a better sense of the countries to non-Koreans whose primary knowledge might come through pop-culture stereotypes and the occasional news story. He reels off the reigning perceptions: “Samsung or smartphones, K-pop in the south, and then in the north it’s this crazy guy who oppresses his people.”

There’s more than that to both countries, but the multibillion-dollar K-pop industry pervades life in South Korea—and filters much of Yoo’s, and the world’s, understanding of both countries. In recognition of pop culture’s sway, art and entertainment tell much of the story in The Koreas.

For example, to illustrate the autocratic rule of Park Chung Hee, South Korea’s president from 1963 to 1979, Yoo tells the story of Sin Junghyeon, “the godfather of Korean rock music.” One of many people victimized by the 1972 Yushin Constitution, which gave the president essentially unlimited powers and no term limits, Sin was persecuted for refusing to write a song for Park.

Pop culture was one of Yoo’s first avenues into Korea. In his graduate school days he made frequent trips to video stores on Chicago’s Lawrence Avenue and spent “more time watching [K-dramas] than trying to read Foucault.” His favorites: Daejanggeum (Jewel in the palace), Anae ui Yuhok (Temptation of wife), and Na-ui Aieossi (My mister). The first time he returned to Korea since leaving as a toddler—on a Fulbright grant while getting his PhD—it all looked familiar. He’d seen it on-screen.

For years Yoo kept the vocation of Korean history separate from his avocation of Korean art. But while working on It’s Madness Yoo struggled to find much written about mental illness in Korea, where it is still heavily stigmatized. He found that novels were a useful indicator of societal attitudes and a primary source in their own right.

“There are all kinds of sources,” he says.

In fact, art stood in for hard news in The Koreas’ epilogue. Yoo had planned to end the book with the 2019 summit in Vietnam with US president Donald Trump and the leaders of North and South Korea. When nothing noteworthy happened, he turned instead to the 2018 South Korean psychological thriller Burning, analyzing the film as “a commentary on the new generation’s unease about their future in a world where precarious global markets have harmed their chances at stable employment and precipitated downward mobility.” Burning was its own kind of historical document: a glimpse into the outlook of contemporary young South Korean adults.

Had he waited longer, Yoo said he could have talked about income inequality in the south as depicted in a better-known Korean film: the multiple-Oscar-winning Parasite (2019), which came out just as he submitted his manuscript.

As a professor at Yonsei University and resident of 21st-century Seoul, Yoo has a new relationship to the country of his birth, where life moves at a breakneck pace: it’s “one of these weird places where restaurants don’t last for more than three months.”

His next books will examine both the past and present. One is a history of feces in Korea—at the risk of essentializing, Yoo describes Koreans as “completely fixated [on] shit”—and the other is a Proustian exploration of Seoul. As a side project, he and his students are developing a virtual reality game to teach Korean. Players assume the identity of a new arrival to Seoul and try to make their way around the city while learning the language.

Yoo got the idea for the game thinking about the people from around the world who arrive in Seoul today: migrant workers. K-pop fans. Adoptees visiting their country of birth. Returning emigrants. And a few escapees from the north, like his parents. All of them, like him, trying to understand Korea and its place in their lives.