Fredi Washington chose not to pass as her character Peola Johnson did in Imitation of Life. “I want to be what I am, nothing else,” she said. (Photo collage created using stills from the Imitation of Life movie trailer, {{ PD-US }})

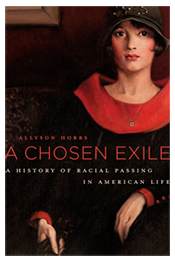

Excerpt from A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life by Allyson Hobbs, AM’02, PhD’09.

“Going as white” permanently created confusion as some family members disappeared across the color line, creating gaps in family genealogy.One woman explained, “My father’s people, half of them pass for white so naturally I know nothing about hardly any of them.”

“Going as white” permanently created confusion as some family members disappeared across the color line, creating gaps in family genealogy.One woman explained, “My father’s people, half of them pass for white so naturally I know nothing about hardly any of them.”

For others, embarrassment and shame prevented an open discussion of family history: “Not much has been disclosed about the Patterson family. It is our guess that there were too many blood mixtures of which the immediate family is not any too proud to relate. ... That this family has many skeletons is without a doubt true.”Merthilda C. Duhe wrote that her father used passing as a strategy to create a new life for himself; she knew little about him or his family because he left New Orleans and “deserted the family while they were very young and went over to the white side in Chicago.”

Others expressed uncertainty about the racial backgrounds of their ancestors. One man questioned his grandfather’s race and explained, “Father was always sensitive about that side of his family.” When asked whether her relatives in Detroit “go for colored or do they go for white,” Mrs. Clemens responded, “I don’t know, and I don’t know what I am. We are 100 per cent American and that is all we can say.” Raymond Brownbow did not know much about his maternal grandmother, a mixed- race house servant who was “described as being very nearly white.” As he explained, “I know very little about her, because it seems that my mother was and is a bit reluctant to discuss her. I remember my mother once telling me that she couldn’t stand the remarks that people would make upon learning of her mother’s mixed blood, and for that reason she refrained from talking much about her.”

Others had no choice but to rely on rumors and speculations as to the whereabouts of family members. The only information that Anthony Driver Chase could cobble together about his grandmother, Hester Ann, was that she was “light enough to pass for white and had long red hair which reached her waist”; her father was a slaveholder; and she had a brother who “went west, married a white woman and passed for white,” and “it is rumored that he became wealthy.” Some family members were able to pass whereas others could not. One relative hinted that other family members passed by explaining, “Margot did not know much of her origin. It seems that her brown skin had been responsible for her separation from the rest of the family who were blonde.”

Other families risked exposing relatives who had crossed the color line by providing too many details about their background. In response to sociologist E. Franklin Frazier’s request for his family’s history in 1932, T. S. Inborden explained, “I will say that I have not more than one sixteenth Negro blood in me if indeed that much. The rest is Mohawk and Caucasian. To publish this would cause a lot of talk and embarrassment. The first Governor of Texas was ... perhaps half brother to my grandmother.”

Others lacked critical information to piece together their family histories. Emblematic of the tensions created by passing, such omissions and doubts led to profound feelings of desertion, disconnection, and incompleteness. One man, describing his great uncle, explained, “I know of one brother, [the] father of a large family. They passed over into the other race and were finally lost to those who remained in the negro race.” Trying to make sense of an absent father who “looked like white,” Pearle Foreman wrote, “The strangest thing was, no one ever told me about my father’s people or from whence he came. I have not been able to find out any information concerning him, only that I resemble him in every respect.” Once family members “crossed over,” they were usually lost, essentially dead to their families.

But the equation of passing to death too quickly dismisses both the ambiguity and the logic of passing, as well as the tolerance and understanding that family members extended to those who passed. Why else would a relative agree to work as a maid in a family member’s home in the interest of continuing an untenable relationship in the Jim Crow era? As passing disrupted family life and made certain topics of conversation awkward if not impossible, it also called into question one’s own identity and sense of personhood. The question that Day Shepherd, a Chicagoan who lived on both sides of the color line and whose daughter wrote about her life in Another Way Home: The Tangled Roots of Race in One Chicago Family, posed—“How would anybody know who they were without their people?”—suggests much broader and more intimate meanings of race and racial identity and reveals the interconnectedness of notions of self and family.

In every historical period, there are those who decide against passing, even though they are often mistaken as white. Fredi Washington first appeared as a chorus girl in Shuffle Along (1921), one of the most successful African American Broadway musicals, but she is best known for her role as Peola, a light-skinned black woman who breaks her mother’s heart by choosing to pass as white in the 1934 film Imitation of Life. As Esquire magazine reported in 1935, the scenes between Peola and her mother stole the show: “The tragedy of the colored girl trying to pass for white completely overshadows the artificial little troubles concocted for the white folks: the audience leans intently forward whenever Louise Beavers (Aunt Delilah) or Fredi Washington (the daughter) is in the scene and simply relaxes even during the dramatic moments of the story proper.” In May 1935, Universal Studios reported that Imitation of Life was the largest grossing film of that year so far, which led many movie houses to return the film to the screen.

Washington’s appearance—her blue-gray eyes, white complexion, and light brown hair—and her compelling performance in Imitation of Life led some of her fans to presume that Washington had firsthand experience with passing. Washington explained, “If I made Peola seem real enough to merit such statements, I consider such statements compliments and makes me feel I’ve done my job fairly way,” but she was clear that her “private life is in no way similar to that of Delilah’s daughter.”

When the German philanthropist Otto Kahn saw Washington dancing at Club Alabam in Manhattan and suggested that she change her name and pass as French, she responded, “I want to be what I am, nothing else.” Washington was often asked why she chose not to pass. She would reply, “Because I’m honest, firstly, and secondly, you don’t have to be white to be good. I’ve spent most of my life trying to prove that to those who think otherwise. ... I am a Negro and I am proud of it.” Washington would allow whites to speak disparagingly about African Americans and then shock them with the truth about her racial identity. In the presence of whites who assumed she was white too, Washington remarked, “I give them plenty of rope. ... I let them talk, hang themselves, and then I quietly say, ‘I’m Negro.’”

Washington did pass as white occasionally. When she was traveling through the South with Duke Ellington and his band, she would go into ice-cream parlors and buy ice cream for the band members, who were excluded from restaurants. Whites called her a “nigger lover.”

Described as “honest, sincere, and fearless,” Washington rarely held her tongue. She was a passionate spokesperson for blacks in theater and film, she founded the Negro Actors Guild in 1937, and she wrote a column called “Fredi Says” for the People’s Voice, the progressive weekly published by Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the pastor and first black politician to represent New York in Congress. She was an outspoken critic of black artists whose calls for equal rights were not loud enough. Washington perceived the struggle for civil rights as a lifelong battle: “I am here as a Negro—then that’s the way I’ll be and I’ll fight until the day I die—or until there isn’t anything left to fight against.”

In stripping away one’s ascribed status, passing offers a sharper angle of vision onto the personal meanings of racial identity from the perspective of black individuals and communities. The communal politics of passing demonstrate the insufficiency of explanations of passing as a rebellious, individualistic practice and instead reveal the ways that race operated on the most private levels and in the innermost reaches of black communities. Passing—the vexed decision to break with a sense of communion and walk away from what was most precious about African American life—is a vehicle to recover and to concretize the most elusive and intimate meanings of African American group identities.

At the conclusion of a 1952 essay, Langston Hughes described the moment when he arrived at the Haus Vaterland in Berlin and two black waiters greeted him enthusiastically: “Hey now! What gives in Harlem?” This exclamation, uttered several thousand miles away from the “Race Capital,” is reminiscent of the question, “who are your people?” as it suggests an elastic sense of connection and kinship, grounded in the sharing of something much more elusive than skin color or residence in Harlem.

A similar experience occurred when Hughes was in Shanghai: riding in a rickshaw, he saw a “very colored man” in another rickshaw, traveling in the opposite direction. As the two made eye contact, the following exchange occurred: “As soon as we spied each other through the traffic in the busy street, he half rose and I half rose, and both of us yelled, ‘Hy!’ The rickshaw went on. I never saw him again the whole time I was in China. I never knew his name. But race had greeted race across space. And I remember his grin much more clearly than I remember the features of any of the [other] faces.”

To be sure, in these foreign contexts, it was skin color that allowed Hughes to make these connections and to recognize the waiters in Berlin and the “very colored” man in the rickshaw in Shanghai. But was it really race that “greeted race across space”?

As the experiences of many of those who passed as white as well as many of those who were left behind reveal, race is so much more than this. Race functions as a proxy for a shared and expansive set of experiences, memories, jokes, stories, and songs. It was only because “race” was so much more than either biology or shared oppression that Hughes could find the grin on the “very colored” man’s face so memorable.

Published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2014 by Allyson Hobbs. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Video

Allyson Hobbs shares a personal and historical perspective on racial passing.