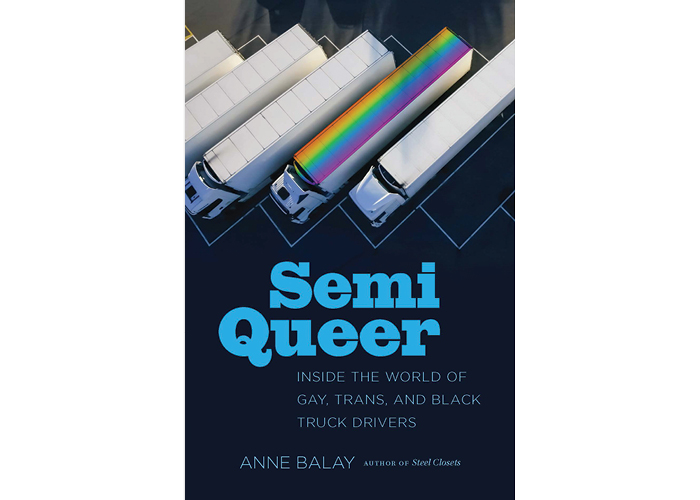

Anne Balay, AB’86, AM’88, PhD’94, has worked as a mechanic and a trucker. “I love the mental state long drives put me in; they’re pretty much the only time I feel relaxed,” she writes in Semi Queer. “I love that feeling, and almost every trucker I’ve talked to does too. That’s what we mean when we say trucking is addictive—it’s not just a job but a lifestyle.” (Photography by Riva Lehrer)

It’s time to rethink stereotypes about American truckers.

When Anne Balay, AB’86, AM’88, PhD’94, set out to interview queer and minority truckers for her new book, more people volunteered than she had time to meet.

This wasn’t the only thing that surprised Balay in researching Semi Queer: Inside the World of Gay, Trans, and Black Truck Drivers (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). “My impression of truckers was that they were straight white guys hostile to queer life and ways of being, and that’s not true at all,” she says.

Demographic statistics are limited, but according to Balay’s research, about 5 percent of truckers are women, and 8 percent are African American or Latino. (It’s not known how many are both.) While no official data are kept on gay and transgender truckers, Balay’s sources described a changing industry. “There’s enough of us out here now that we can feel more bold, and be more visible,” one trans trucker told her.

Semi Queer weaves together a history of the trucking industry and the oral histories of 66 anonymous truckers. In theme-driven chapters, the book explores truckers’ experiences with road accidents, post-traumatic stress disorder, and bias.

Many of Balay’s narrators arrived at trucking as a job of last resort. They had suffered harassment and discrimination at previous jobs, or couldn’t get hired at all because of their visible queerness. One trans narrator, Liam, described the challenge of having a limited work history under his new post-transition name. Because it requires little contact with other people, trucking provided a comparatively safe and accessible option.

Balay herself worked as a trucker after being denied tenure, a decision she believes was motivated by homophobic discrimination. Jobless and panicking, she entered trucking school because she’d always liked driving. There she found that sitting in the cab of a truck was transformative. “Suddenly all of the anger and bitterness just flowed away. I felt like this is something I could do that would be meaningful and productive,” she says. (Balay has since returned to academia and now teaches at Haverford College.)

Her experience was not uncommon. Mastering an 80,000-pound piece of machinery offered many of Balay’s interviewees a sense of power. As one driver told her, “the fact that people hate me ’cause I’m trans, well then they’ll hate me, but say hello to my truck.”

With its constant motion and cycles of departure and arrival, Balay writes, the everyday life of a trucker is well suited to individuals whose gender identities are also in flux. Trucking offers a way for these individuals to express their shifting identities more openly. “Out here on the road I live authentically,” explained Alix, who is trans. “I am kind of leading a double life because when I go home, I’m kind of mom to the kids. … So when I get back into the truck, it’s liberating, because I don’t have anyone’s expectations to live up to.”

But the profession has drawbacks. Nonwhite truckers experience racism from the carriers that employ them, other truckers, and customers. For all drivers, “trucking is incredibly dangerous,” Balay says. Apart from the risk of accidents, drivers are frequently alone in remote areas or at truck stops, which can be magnets for illegal activity. Sexual assault was common among the women she interviewed, both cisgender (those whose gender identity matches the sex on their birth certificates) and transgender. Nearly every trucker Balay interviewed carried a gun.

Then there are the looming existential threats. Technology has transformed trucking, adding new forms of employer surveillance, such as cameras and speed sensors, that many drivers feel are needless micromanagement. The most dramatic change awaits as self-driving vehicles threaten to upend the industry. Balay worries for the marginalized truckers for whom “there are no other decent jobs available.”

But until autonomous trucks hit the interstate, truckers will remain essential, linking even the most remote parts of the country to the web of American industrialism. That sense of connection to how things are made is one of the reasons Balay found satisfaction in driving a truck. Her work took her to the mills where toilet paper is made, the Nabisco factories where Oreos emerge from conveyer belts, the fields where fruit is grown and picked. She saw it all, and took it where it needed to go next.