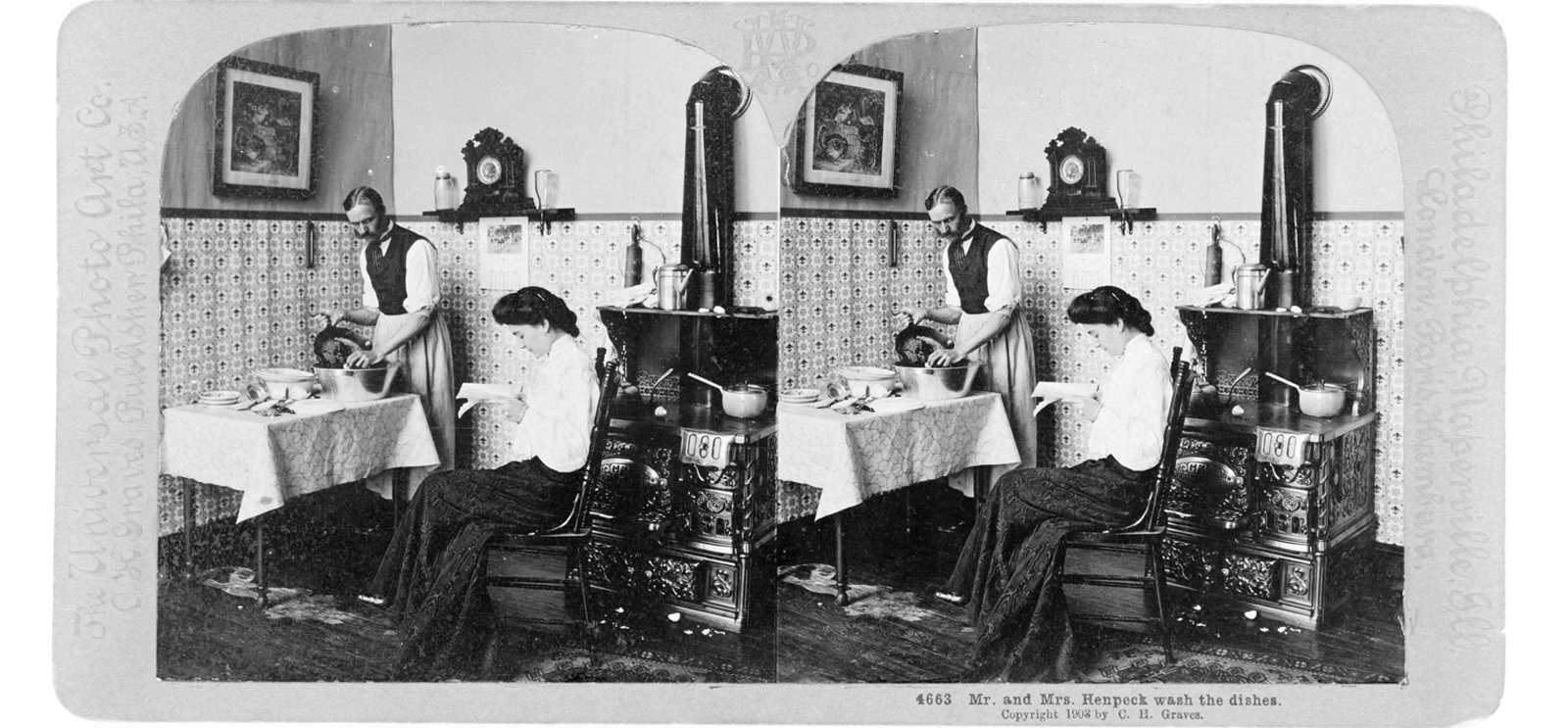

C. H. Graves, Mr. and Mrs. Henpeck Wash the Dishes, 1903. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC)

Exploring the serious questions of humor in photography.

Delightful, spooky, and dark images fascinate Louis Kaplan, PhD’88, professor of history and theory of photography and new media at the University of Toronto. The author of books such as The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer (2008) and Gumby: The Authorized Biography of the World’s Favorite Clayboy (1986), which he cowrote as a fun distraction from his thesis, Kaplan published Photography and Humour with Reaktion Books in late 2016. Says Kaplan: “We need humor now more than ever.”

Delightful, spooky, and dark images fascinate Louis Kaplan, PhD’88, professor of history and theory of photography and new media at the University of Toronto. The author of books such as The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer (2008) and Gumby: The Authorized Biography of the World’s Favorite Clayboy (1986), which he cowrote as a fun distraction from his thesis, Kaplan published Photography and Humour with Reaktion Books in late 2016. Says Kaplan: “We need humor now more than ever.”

What does humor have to do with the social sciences?

There is the social function of photography, the fact that it acts as a social bond and a source of integration. Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist, wrote a book on this, Photography: A Middlebrow Art. There is a chapter in my book called Social Snaps, about the ways in which these photos can also serve disintegration. I talk about a genre of stereoviews from the 19th century that are all about making fun of domestic happiness, like the domestic TV comedies that people are still familiar with—that’s how that visual entertainment took shape in the 19th century. Each chapter of my book is organized around ways in which we have conceived photography’s being in the world and genres that make fun of these theorized functions.

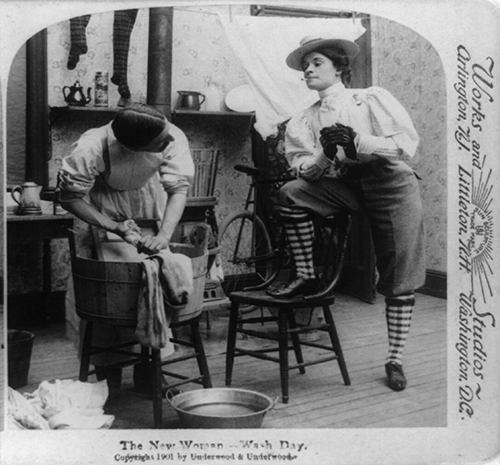

Underwood & Underwood’s 1931 image The New Woman—Wash Day mocked the woman’s liberation movement, implying the reversal of gender roles brings emasculation. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC)

Underwood & Underwood’s 1931 image The New Woman—Wash Day mocked the woman’s liberation movement, implying the reversal of gender roles brings emasculation. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC)

In the book you quote Charles Dickens: “When photography tries to be funny, there is one, and only one result: vulgarity, and vulgarity of the most tragic and lachrymose kind.” Why did he take such issue with the genre?

He’s writing at a time when photography is just making the scene. There’s a fear that the visual humor will be a competition for literary humor, and so he’s trying to discipline that new type of humor out, and he does it by being contemptuous and belittling it. In a way it’s ironic because Dickens was a very popular writer. He was always appealing to the masses and to the base instincts in a lot of his writings.

What attracted you to UChicago’s Intellectual History program?

My undergrad degree at Harvard was in social studies—an interdisciplinary program that covered social sciences including social and political theory. What attracted me to Intellectual History was its interdisciplinarity, its ability to cross borders like my undergrad program. I specialized so I wouldn’t have to specialize.

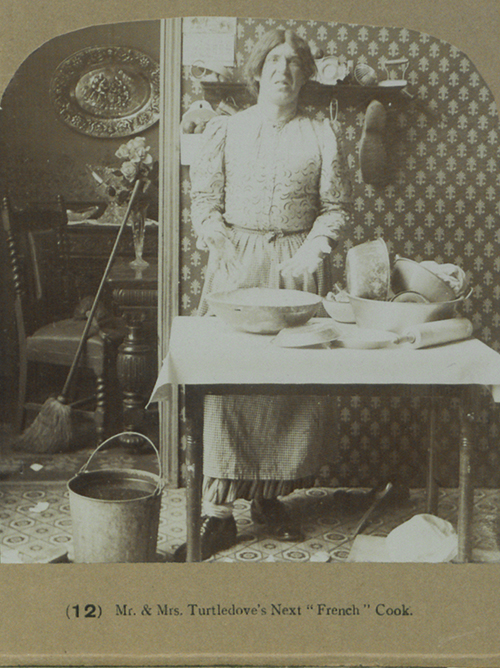

Arthur Lawrence Merrill, Mr. and Mrs. Turtledove’s Next “French” Cook, 1906. (British Library’s Canadian Colonial Copyright Collection, London)

Some of the images in the book are morbid or even racist: Why did you include those?

One of the functions of photos is that we have them in order to remember: photography marks our relationship to our mortality. And humor is disturbing—let’s not deny that. My first chapter gives an overview of some basic philosophical approaches to humor, and one of them comes out of Thomas Hobbes. He’s not a very happy guy. He theorized that humor is based on what he called Superiority Theory. It’s not about laughing with, it’s about laughing at. Laughing at is cruel.