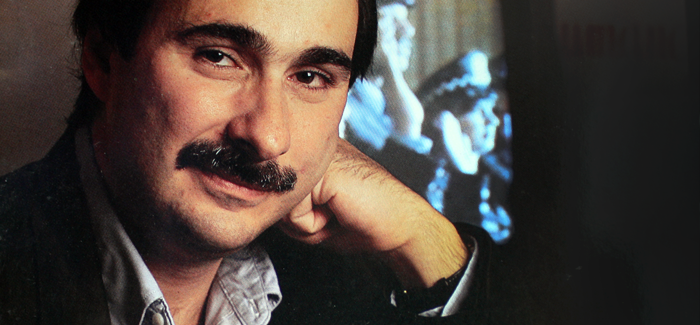

David Axelrod, AB’76, reflects on helping politicians fine-tune their media messages. (Photography by Dan Dry)

From our print archive: With a killer instinct, David Axelrod, AB’76, creates messages that turns political candidates into winners.

It’s the Monday after July 1992’s democratic national convention, and David Axelrod is tired. Very tired.

So his friends say. You wouldn’t really know, just meeting him. It could be that his characteristic wit is off a quarter-beat, but he still manages to roll off the quips:

“People talked about Dukakis being the victim of character assassination, but I’ve always described it as character suicide.”

“It would take an extraordinary opportunity to get me to move to Washington. I don’t have Potomac fever. I think Potomac fever is a step on the road to madness.”

“You know, one of Bill Clinton’s big problems is that he speaks in 40-minute sound bites.”

Axelrod—called a “rising star” in national Democratic politics by the newsletter Campaigns and Elections—gained national recognition in 1984 as manager of the Illinois campaign of Paul Simon, one of just two Democrats to oust Republican senators as President Ronald Reagan swept 49 states. After that victory, Axelrod managed to build the first successful Chicago-based political consulting firm. His clients have included Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, the late Harold Washington, former US Senator Adlai Stevenson III, and Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton. At 37, Axelrod, AB’76, has become a player in the corridors of power to a degree that—as a journalist fresh out of the University of Chicago, covering politics for the Chicago Tribune—he could once only fantasize about.

A profile of Axelrod in the Tribune last spring suggested that his departure from journalism was motivated by a desire for “more money, more power, more action.” This image—of a once idealistic newsman turned campaign mudslinger—emerged full-blown last winter in the Chicago press when Axelrod took on AI Hofeld as a client. Hofeld, JD’64, spent millions, much of it his own money, in an attempt to defeat incumbent Illinois Senator Alan Dixon, in what the Tribune called one of the most bitter primary campaigns in recent history. Both men ran aggressively negative ads about the other and, in the end, both lost to a virtual political unknown named Carol Moseley Braun, JD’72, who is running in the general election this fall against Republican Rich Williamson.

Two days before the March primary, the Chicago Sun-Times ran an editorial titled “Axelrod Engineers Mudslide for Hofeld” in which the paper’s political editor, Steve Neal, called Axelrod “the Mr. Flexibility of Illinois politics. ... Though he insists he won’t work for just anyone, he is flexible in choosing clients. ... Axelrod goes where the money is.”

There’s no question that Axelrod has made more money since switching careers. His firm, Axelrod & Associates—which employs seven public relations and media specialists, one who works in Washington—placed $7 million in advertising in 1991, which wasn’t even a major election year. But it’s hard to ascribe money-and-power motives to a decision Axelrod made last year, turning down an offer he seemingly could not refuse: to become Bill Clinton’s full-time media specialist. Axelrod did help Clinton set up his current campaign crew, and his advice was essential to the Democrat’s crucial Illinois primary victory. He also pitched in on Clinton’s well-received acceptance speech at the July convention, and he will remain on retainer with the campaign throughout the election. Still, it’s clear that he passed on a major business opportunity in declining Clinton’s original offer, but that doesn’t seem to bother him. “I can always go and make money,” he explains, “but the family considerations were such that I couldn’t—you know. I’ve got three kids. And I simply couldn’t abandon my family.”

In a business all about creating image, Axelrod maintains a decidedly relaxed facade, preferring T-shirts, baggy pants, and sneakers to silk ties and Armani suits. When he does wear a tie, as often as not it will show some visible evidence of a past, quickly eaten meal. His own mother once compared his demeanor to an unmade bed. Axelrod tends to shake his leg when he talks, and he talks all the time. Negotiating his Saab through snarled traffic from the Oak Park home he shares with his wife, Susan, MBA’82, and their three children, to his office suite in the chic River North district, he clings to his cellphone like a lifeline.

His bare cupboard of an office is sprinkled here and there with framed mementos (including a note from one politician thanking Axelrod for not taking on her opponent’s campaign), family pictures, an ancient Schlitz trophy that stands waist-high. With a focused, driving energy, he talks of his life’s great passion. It’s not money that’s got David Axelrod revved up on a day when he has every right to be tired. It’s politics.

That passion for politics seems almost a genetic imperative. Soon after learning to read, Axelrod remembers rushing to the doorstep of his parents’ Manhattan apartment in the early morning to scan the headlines of the New York Times. Axelrod’s father was a psychologist; his mother, a freelance writer who later became “sort of a pioneer in qualitative research” in advertising for the New York firm of Young and Rubicam. Both were “your classic New York leftist Democrats” for whom politics was standard dinner-table conversation.

“I remember going to see John F. Kennedy on the street corner in 1960 when I was five years old,” says Axelrod, “and I remember when I was nine handing out leaflets for Robert Kennedy, who was running for the Senate.” He looked forward to visits from his parents’ precinct captain the way some kids anticipate the jingle of an ice cream truck.

At 17, Axelrod arrived at the University of Chicago campus, intent on pursuing his political interests, although he wasn’t sure exactly how. “I was struck by what an extraordinary social and political environment Chicago was, and I was disappointed that the University didn’t do more of a contemporary nature. It seemed to me—l was in political science—there was very little interest in things that happened after 1800.”

Among the students, Axelrod also found that “interest in politics was pretty dormant back then, and there was a certain introspective and cloistered feel to the campus that really frustrated me. I think it’s much different today, actually. I think that what happened was that there was this burst of activity in the late Sixties and then a real effort to filter out that sort of activism and sort of quiet things down.”

Axelrod vented his frustration by writing about local politics for the Hyde Park Herald, which led to stringing assignments for Time magazine. Upon graduation, he’d built up enough clips to get a summer internship at the Chicago Tribune.

“That summer led to a full-time job,” he recalls. “I was on nights covering fires and homicides and all manner of disasters, and I spent my free time trying to dig up little political stories to insinuate my way onto the political beat. They used to throw me some bones every once in a while to reward me for my efforts.” One bone tossed his way in 1979 was “this clearly doomed, kind of fanciful campaign,” Jane Byrne’s first run for Chicago mayor. He’d never cover another fire.

Throughout her campaign, Axelrod wrote rapturously about Byrne’s platform of reforms—stories he now has little doubt helped get her elected. “Perhaps I was guilty of naiveté as a 24-year-old kid,” he says today, “although so was virtually the entire press corps. The only guy who was really jaundiced about her from the very beginning was the late Harry Golden, Jr., who was dean of the city hall press corps and knew her well and thought, in his words, that she was a ‘horrible faker.’ And, in fact, that’s what she turned out to be.”

After Byrne’s election, Axelrod detailed in stories—and, later, in his own column—how the mayor had “systematically broken all her campaign promises.” In response, Byrne tried to have the young reporter barred from city hall, an attempt that only enhanced his career—by 1981, he was the Tribune’s top political writer. Four years later, he stunned colleagues with the announcement that he had “succumbed, after months of resisting,” to Congressman Paul Simon’s opportunings that he serve as press secretary in Simon’s Senate race against three-time Republican incumbent Charles Percy, AB’41.

“I loved the newspaper business,” Axelrod says of his departure. “But I think too many people in journalism make the mistake of staying too long and end up on the rewrite desk on some outpost, writing about the Lombard Lily Festival. … I think it was a smart idea to get out while I was on top, rather than waiting to be forced out.”

What Simon—a downstate politician with few friends in the Chicago press corps—wanted was Axelrod’s media connections, but what he got was “a political message genius,” says Forrest Claypool. Claypool, currently Illinois deputy state treasurer, had joined Simon’s campaign on something of a whim, acting as communications aide through the primary, “but they traded in their Chevy for a Cadillac when David arrived.” Within a short time, Axelrod was promoted to campaign manager.

“He was like the backup quarterback who’s been waiting on the sidelines to test out his arm in the big game,” says Claypool, “and he finally got his big shot. I think he wanted to test his skills in the arena of political combat, as opposed to being a journalistic observer, and I think he felt supremely confident—he immediately went in and took command of the message of the campaign, which was sorely in need of message-direction.”

The message, in a nutshell: Percy was more interested in globe-trotting, foreign affairs, and meetings with the Dalai Lama than in the hard, unglamorous task of assisting Illinois business and workers through hard times. “People in the state were really suffering back then,” says Axelrod. “We were in the midst of a harsh recession, and I felt that we ought to be fairly straightforward about our attack. … It all came down to ‘Who can you count on?’ We drove the debate that way.”

“David’s very good at political intrigue,” Simon said after his election, “and I don’t mean that in a negative sense.”

Axelrod turned down Simon’s offer to join his staff in Washington. Instead, he and Forrest Claypool decided to start their own, Chicago-based, media-consulting business, setting up shop in borrowed office space—and on borrowed time.

“In those days, every campaign seemed make-or-break,” says Claypool. The problem for new kids on the consulting block is that they tend to get the “hopeless” campaigns—neophyte challengers who could only afford the bargain basement fees that Claypool and Axelrod were offering. To become established in the business, they had to tum those hopeless campaigns around. It didn’t always mean winning, says Axelrod, but it did mean “beating expectations—doing better than anyone thought you had a right to do.”

One early campaign was for Wayne Cryst, a Missouri farmer running for Congress. Cryst had become something of a folk hero in the early Eighties when he raided and removed his soybeans from a grain elevator after they’d been seized by federal creditors. By the time Axelrod and Claypool were brought in, Cryst’s quixotic campaign trailed badly in the polls. “His campaign manager had, unfortunately, not managed the store too well, and he had blown most of his money,” says Claypool. With the little cash left—and money out of Axelrod’s own pocket—he and Claypool whipped out a series of television ads focused on Cryst’s down-home appeal. The farmer lost by only four percent of the vote.

A 1986 race for Kentucky’s vacant attorney general post ended in victory for another political unknown, a state legislator named Fred Cowan. “We started out 33 points behind,” says Claypool, “and then David crafted some hard-hitting spots that tied Cowan’s opponent to a series of legal and ethical lapses over the years, questioning his judgment and integrity. I remember that towards the end of the campaign, the candidate’s wife and all his aides were challenging David’s strategy, saying we needed to talk about what a good person Cowan is—because he was, in fact, a good person and he had a great record in the legislature.

“But the point was, Cowan was totally unknown—running against a guy with 90 percent name recognition—with limited time and a limited amount of money to spend. David’s view was, the only way you can win is to make this a referendum on your opponent. In other words, make that person’s name recognition work against him by showing that he’s a bad risk for the job.” Cowan ultimately backed Axelrod; but Claypool vividly recalls the harsh glares cast their way from Cowan’s camp on election night, turning to warm smiles as it became clear their candidate, and Axelrod’s roll-of-the-dice strategy, were winners.

What really put Axelrod on the media consulting map was Harold Washington’s 1987 primary race for mayor against Jane Byrne. Axelrod anticipated that the white Byrne would go after the black Washington on two issues “that would be code words for race, and those were taxes and crime. And indeed, that’s where she went. The challenge was to make people understand that she was a former mayor and that her record on both was terrible compared to Washington’s. So we did two comparative spots, one on crime and one on taxes, that I think effectively ended the election.” Byrne has since agreed that Axelrod’s “attack” ads were decisive in her narrow loss.

In 1982, while still reporting for the Chicago Tribune, David Axelrod wrote a profile on Richard M. Daley, at that time Cook County state’s attorney, whose late father ruled Chicago politics for decades.

“As Daley fields questions, he behaves a bit like a man in a dentist’s chair,” Axelrod observed. “He squirms in his seat, checks the clock periodically, and approaches every turn in the conversation anxiously, as if something might be awaiting him around the bend. When his father was alive, Daley routinely spurned reporters, suspicious that any story would be an attempt to embarrass him or the mayor, and perhaps aware of his own shortcomings as a speaker. ... But today, Daley grudgingly accedes to interview requests, mindful that the news media, particularly television, has replaced the precinct captain as the tool that shapes a politician’s public image.”

Axelrod admires Daley, son of the ultimate machine politician, for his smarts in realizing the machine was on the fritz; that TV, not party politics, was the new kingmaker. Daley also had the smarts to hire Axelrod to do the media for his 1988 mayoral race. Although Axelrod was approached by every other Democratic candidate running, he chose Daley “because I felt most comfortable with him.” Axelrod helped the candidate improve his faltering speaking skills and overcome his image as “Dumb-Dumb Daley” (as one opponent nicknamed him), shaping a strategy and message that produced a landslide victory.

If party loyalists couldn’t take credit for the win, at least it was a victory they could swallow. Not so with Axelrod’s choice of candidates in the 1990 primary race for the powerful and mysterious post of Cook County Board president. Axelrod bucked the party’s choice, backing millionaire Winnetka lawyer Richard Phelan. After financing Axelrod’s media blitz, Phelan wound up winning the four-man race, with party favorite Ted Lechowicz finishing third. The candidate who placed last, Stanley Kusper, moaned afterwards that Phelan had “bought the election”—not under the table, but over the airwaves. “I would think,” said Kusper, “that anybody who really wants to win from now on is going to have to have the money to go to TV and radio. If they don’t, they won’t win.”

Phelan tells the Magazine it wasn’t just money that won him the election: it was Axelrod. Late in the campaign, his opponents were having success framing him as a starchy North Shore dilettante. A poll showed Phelan slipping.

“We got the poll on Friday,” says Axelrod. “I literally woke up with this idea for a spot on Saturday, which actually happens to me a lot.” Axelrod knew of a popular tavern called Coogan’s that Phelan frequented for lunch (in fact, Phelan owns the establishment). On Sunday, Axelrod had Phelan in the bar, shooting a spot, run on local TV channels the following Monday, in which the candidate confides how his parents sacrificed so he could study law at Notre Dame. His opponents, Phelan warns, claim he is “too successful” to govern Cook County, but that’s because they know “I’ll run things for the taxpayers, and not political insiders.” The clincher comes when Phelan turns toward the bartender, who sets down a beer. “Or did you want yours in a champagne glass?” he asks. Phelan just grins and replies, “Get outta here!”

“You see, you laughed!” says Phelan, recounting the commercial with obvious glee. “That was the whole point. It was sheer genius, that’s the only way I can describe it.”

From the reported $1 million Phelan spent on the commercials, Axelrod got 15 percent of the media buy, plus a consulting fee. Yet he denies he backed Phelan—and bucked the party—strictly for money. “If the party structure had prevailed,” Axelrod says, “then Ted Lechowicz would have been the candidate for president. And I don’t think there’s any question that Dick Phelan is a better county board president than Ted Lechowicz. If the party structure had prevailed, Pat Quinn wouldn’t be state treasurer. He’s certainly the best state treasurer we’ve had since Adlai Stevenson.”

“I’ve worked for people with lots of money and I’ve worked with people for no money,” Axelrod recently told the Chicago Tribune. “When Pat Quinn ran for treasurer, I lent him money. If he runs for governor in ‘94, I’ll work for him, and he’ll be the least well-funded candidate in the race.”

His critics may not buy such selfless claims, but there’s little doubt that Axelrod himself believes them. A seemingly indestructible confidence, in both himself and in the candidates he represents, translates to great effect in the award-winning campaign ads that he writes, produces, and directs. While it may be hard for some to distinguish between the “country-clubbing” Republicans that Axelrod disparages and some of the millionaire Democrats whom he’s helped win elections, there’s no mistaking their differences when filtered through the sounds and images of his radio and TV ads.

He will occasionally push the outer envelope of such contrasts. One rather notorious mailing his office sent out on behalf of AI Hofeld against Alan Dixon, designed to look like an American Express brochure, could be mistaken for a rabidly Marxist diatribe: “Money-stained fingers smear fine crystal glasses. Fancy colognes mix with the odor of corruption. Expensively dressed diners can hardly control their obscene appetites for wealth and power.”

More typical, however, are ads like the TV spot Axelrod did for Indiana Congressman Frank McCloskey, in which a woman offers a plain, heartfelt testimonial for McCloskey, whom she says helped keep open the factory where she and her husband worked: “He said he’d help and he did. He saved my job and my family.” The way her voice catches on the word “family” says more about the daily hopes and fears of blue-collar America than a truckload of political speeches.

One Axelrod opponent, declining to be identified, says, “I think we ran better looking spots than [he] did; but they didn’t have the same impact. He’s very good at defining themes that resonate with average voters.” Indeed, not all of Axelrod’s admirers are Democrats. The late Republican national chairman Lee Atwater paid public tribute to Axelrod’s hard-hitting TV ads that linked Jill Long’s GOP opponent to high taxes in a highly publicized 1989 race for Dan Quayle’s old congressional seat.

Axelrod explains his success this way. “I think we understand, as other consultants don’t, that the spots are only the end of a process. And the process is understanding what the message is that’s going to win.”

Partly, it’s having the right instincts, but Axelrod says he also relies heavily on polling, “because the thing you learn very quickly in this business is that people are counter-instinctual. You may think you have the keenest insights in the world, and they will fool you. That’s one of the great things about this business—because one would hate to think that people are so predictable that you can know in every instance how they’re going to react. So polling and qualitative research, focus groups, become very important in understanding people’s attitudes.”

Axelrod also claims he has more success than most consultants in getting cooperation from newspaper and television reporters. It’s hard to imagine Axelrod saying even privately what Republican communications strategist Roger Ailes once said publically about journalists: “F—k the media!” Given a choice, Axelrod would probably still prefer the rowdy camaraderie of a barful of city desk reporters to the staid, Federal Register musings of some Beltway politicos. “I appreciate the role of the press,” he says. “It’s not to coddle the politicians.” And the press mostly seems to appreciate Axelrod. Instead of wasting their time with bad P.R., he gives them meaty leads: even facts about opponents’ shortcomings that he’s dug up himself.

“Many times I’ll talk to them off the record and we talk more freely and they get a sense of where I’m coming from,” says Axelrod. “I never try to intentionally mislead anybody. It’s not only wrong, it’s unwise—because you may get away with it once but in the future it’s going to come back and bite you.”

Ironically, Axelrod says that the most difficult trust to build is with the actual clients candidates who are often wary from experiences with professional consultants who dismiss them as amateurs. In contrast, Axelrod and his associates “recognize that, generally, the campaign manager and the candidate are greater repositories of wisdom about their communities than we are. And, therefore, their ideas have to be taken seriously.”

Likewise, he disputes perceptions that he and other consultants can fill their candidates, like so many empty vessels, with “a load of magic malarkey,” and then get those candidate selected. “I think for a campaign to be effective the message has to really flow from who that candidate is. If the message doesn’t reflect the candidate, people are going to figure it out. And, you know, basically when candidates go out there, they are very much putting themselves on the line. The least you can do for them is to make sure that the message they’re carrying is one they can feel comfortable with.”

“My experience,” Axelrod recently told the Chicago Reader, “has been that, by the end of every campaign, people have made judgments about candidates that are fairly accurate. And in the amalgam of all the spots and all the public debate comes through an image that tends to be fairly accurate.”

He refuses to buy allegations-like one read to him from The Spot: The Rise of Political Advertising on Television by Edwin Diamond, PhB’47, AM’49, and Stephen Bates—that his profession may be harming the democratic process by “turning campaigns and elections into a kind of spectator sport … to watch and enjoy but not necessarily to participate in by voting.”

“Isn’t it interesting,” he says, leaning forward in his chair, jaw tense, “that people would suggest that competition could hurt the democratic process? I think that competition is good for the democratic process. What’s really hurt the democratic process is that officeholders have let people down. I mean, it wasn’t the political consultants who created Watergate or the S&L crisis or the Vietnam War, or all the things that have led to this massive cynicism among voters.”

Still, he concedes, candidates need money to buy media, and so the candidates with more bucks have the advantage. People may point to Carol Moseley Braun and her Illinois primary victory as an example of voters rejecting big-money candidates, but Axelrod says they are missing the point. “Some folks from the Braun camp approached me about her race in the beginning, and I told them bluntly I didn’t think she could raise the money to put a winning campaign together, one-on-one, against Dixon.

“It looked like she was above the fray, but the truth is, she was below the fray. I mean, she really wasn’t involved in the campaign. And just by not being involved in it she looked better than the two guys who were in it. And I’m happy she won. If we couldn’t win, I’m certainly happy she did-I think she’ll be a good, strong vote in the Senate. But the truth is, she could never have beat Alan Dixon if Al Hofeld had not been in the race, spending the kind of money that he spent.”

Given that reality, Axelrod says, the only way to truly help less funded candidates is to offer more “free media” opportunities. “I feel strongly,” he says, “that television and radio stations ought to be compelled, as part of the privilege of using the public airwaves, to give a certain amount of free time to candidates so there is at least a minimal level of exposure for all the candidates. That would do two things: it would make these races more competitive and it would also cut in half the costs of campaigning. And by doing that you’re really reducing the influence of special interests.”

That such changes would also reduce Axelrod’s bank account doesn’t even seem to occur to him, but that’s typical, says Forrest Claypool. “In more instances than I can name, David has basically let his heart get in the way of his head in terms of the financial side of the business. ... That’s an admirable characteristic, but I think it’s also dangerous.”

Even in the unlikely event that Axelrod does one day manage to lose his food-stained shirt—or, more likely, that he simply wearies of the daily stress of media consulting—Claypool doesn’t doubt his friend will land squarely on his feet: “David is going to be one of those people who have four or five careers in their life. Personally, I would like to see him become the editor of a major paper, or perhaps have some sort of strategic or communications role in the White House, with the appropriate Democratic president.”

In the meantime, Axelrod is resigned to the fact that columnists will continue to label him a money-hungry mudslinger; that people, in general, will think of his business as a “dirty” one. Once he gets into a race behind a candidate he believes in, it’s no longer about what his critics or opponents say about him—it’s about winning. And winning is something David Axelrod has clearly not grown tired of.