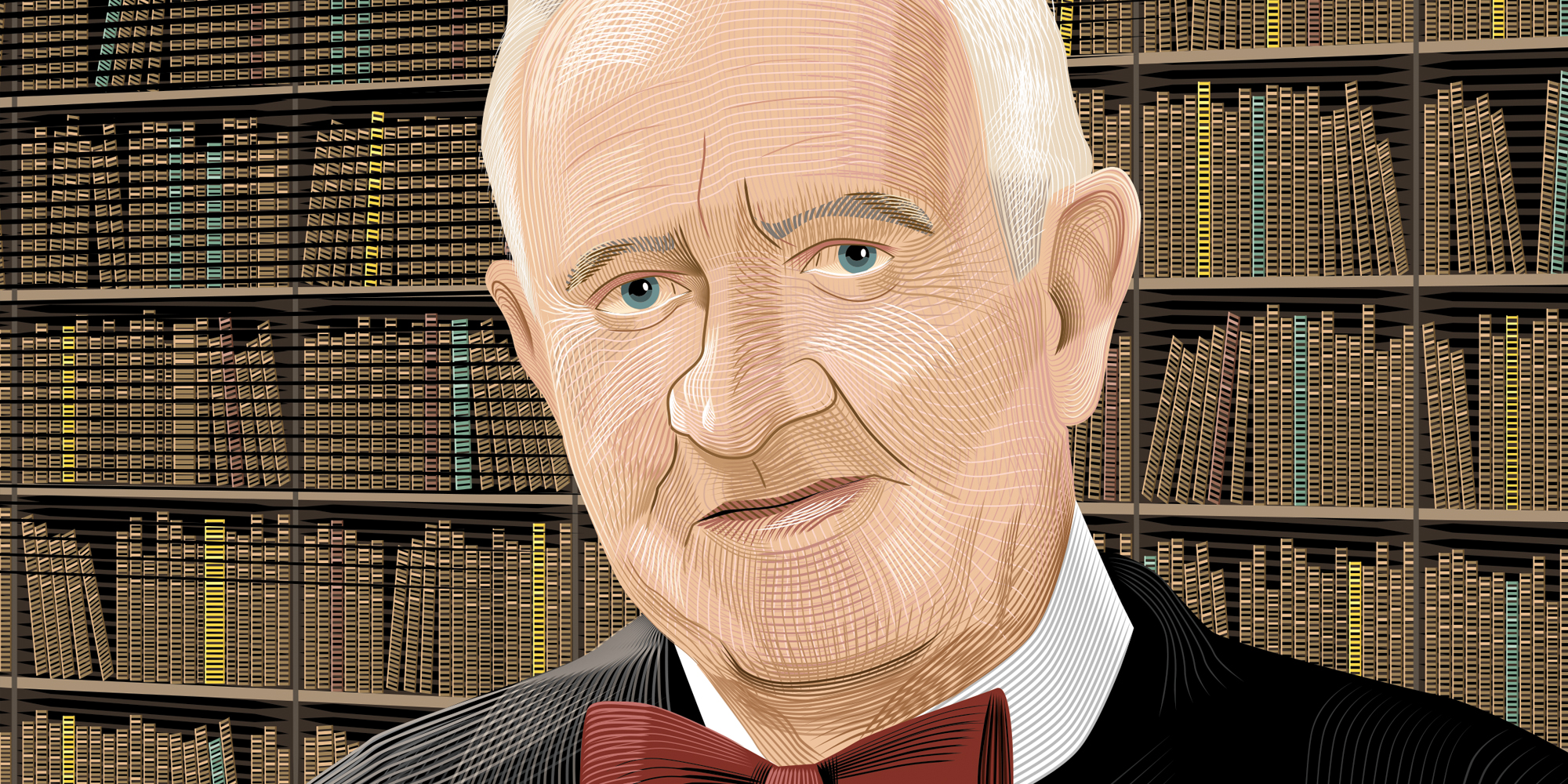

(Illustration by Daniel Hertzberg)

Fellow justices, former clerks, journalists, and court watchers reflect on a singular Supreme Court career.

John Paul Stevens was a Hyde Parker born and raised. He grew up on 58th Street, graduating from the Laboratory Schools and the College, and he remained close to the neighborhood and the University all his life. But the decisions—and the dissents—that he wrote during his 35 years of service, the third-longest tenure of any Supreme Court justice, leave a legacy that is most essentially American.

Respected by citizens of every political leaning, Stevens, LAB’37, AB’41, earned a reputation for being staunchly independent in his thinking, loath to apply rote principle. As much as he influenced US law, the thousands of cases he studied and ruled on influenced him, notably his views on capital punishment and affirmative action, which changed over his career.

His open-minded but rigorous judicial temperament, which compelled Stevens to consider each case on its own terms without preconception or prejudice, shares much with the aims and modus operandi of a UChicago education. He belonged above all to the country, yes. But also unmistakably to this place.

Stevens’s death on July 16 (see Deaths) sparked the outpouring of remembrances one would expect for someone in such an influential and public role for so long. Less common was the warmth of those words—from his fellow justices, former clerks, journalists, and court watchers—as demonstrated by the individual reflections shared here.

Dahlia Lithwick and Sonja West, JD’98, Slate

At times he was a maverick, a frequent lone dissenter, unafraid to stand alone in his convictions. Once, in an interview, Justice Antonin Scalia was asked which justice was his favorite sparring partner, and he named Stevens. “I think you should give the dissenter the respect to respond to the points that he makes. And so did John Stevens,” Scalia explained. “So he and I used to go back and forth almost endlessly.” Stevens, however, was also a unifying leader who will be remembered for his unusually effective ability to unite the four more liberal-leaning justices against the conservative majority.

Stevens was known for being the only justice to write his own first drafts, which he would pass along to his clerks with instructions along the general lines of “don’t let me look like an idiot.” For decades he was also the only justice to rely entirely on his own clerks’ recommendations about which cases the court should hear, rather than pooling his clerks with those of the other justices to review only a share of the petitions as all the other justices did. He reveled in debating with his young clerks, enthusiastically engaging their arguments and humbly treating them as intellectual peers.

David Cole, The Nation

Stevens’s commitment was not to a particular worldview but to the act of judging, which requires fierce independence, an open mind, and the willingness to do the right thing regardless of whether it is popular. He was skeptical of rigid doctrinal tests; he criticized the Court’s equal protection doctrine, for example, which applies different levels of review to laws discriminating on the basis of race, sex, and other classifications, respectively. In his view, there was only one Equal Protection Clause, and he didn’t think that differing tests were very helpful in deciding cases. He trusted his own ability to render judgment over a rigid rule.

Travis Crum, Lecturer and Bigelow Teaching Fellow, University of Chicago Law School

I had the tremendous honor to clerk for Justice John Paul Stevens while he was a retired justice. During my clerkship, Justice Stevens wrote his memoir and often reminisced about growing up in Hyde Park. His stories about Chicago were like something out of a movie. As a child, he watched Babe Ruth hit his famous “called shot” at the 1932 World Series at Wrigley Field, worked at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, and attended several important events at his family-run Stevens Hotel (now the Chicago Hilton). Justice Stevens also spoke fondly of attending both the University of Chicago and the Laboratory Schools.

Despite living one of the most extraordinary lives of the past century, Justice Stevens was one of the most humble people that I’ve ever met. And on top of that, he was a brilliant and visionary jurist. His passing is a huge loss for the court and the country.

Ian Gershengorn, SCOTUSblog

The spate of 8–1 decisions with the justice’s occupying the role of lone dissenter earned him a reputation of being an iconoclast. In the term when I clerked, articles were written calling the justice and his jurisprudence “quirky.” He didn’t like that description, he told us, because as far as he was concerned, he was just doing his job. His reaction captured something important about the justice and his approach to the law. He was committed to getting it right in every case. No issue was too small, and no case too routine, to demand anything less than his full attention and consideration. If his review of the law and the facts led him off on what others thought a tangent, so be it, as he believed that the parties and the court deserved no less. And because of the way he approached his task—with respect for the majority and a calm conviction in his own position—his lone dissents conveyed his views while his relationships with his colleagues remained as warm as ever.

Noah Feldman, Bloomberg

Today’s justices come so vetted to avoid deviation from ideological and partisan pressures. Stevens, the justice from the greatest generation, reminds us that it wasn’t always so—and that great justices develop and change, becoming greater as they go.

Gregory Garre, SCOTUSblog

[Justice Stevens’s] disarming manner of asking questions masked the fact that he often asked the most difficult questions, zeroing in on the key legal principle or fact at the crux of the case, and asking an advocate in the kindest way if they would just agree with him on a point, leaving them to realize only later that they had often sunk their case by doing so. It always reminded me of the detective show Columbo, another link to the past. Just when the lead suspect would think they had gotten away with it, Columbo (played by Peter Falk) would return to the scene of the crime, raise his finger, pause for a moment, and say, “There’s just one more thing.” And that would be the question that did the suspect in.

Waiting for Justice Stevens to ask that question as time was winding down was one of the scariest moments of oral argument.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

In a capital city with no shortage of self-promoters, Justice Stevens set a different tone. Quick as his bright mind was, Justice Stevens remained a genuinely gentle and modest man. No jurist with whom I have served was more dedicated to the judicial craft, more open to what he called “learning on the job,” more sensitive to the well-being of the community law exists (or should exist) to serve.