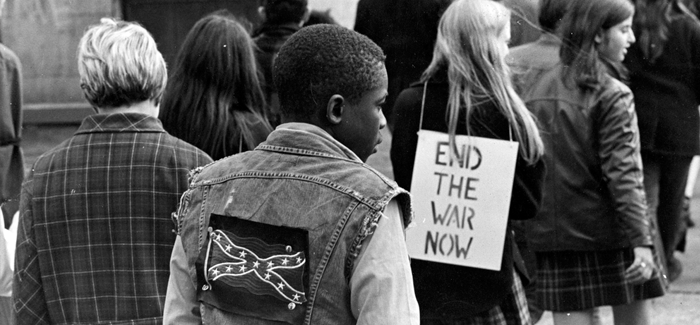

University of Chicago, October 10, 1969: Students march from Hyde Park into Woodlawn during a draft moratorium rally in Chicago, part of a nationwide day of protest against the Vietnam War. (Photography by David Rosenbush/Chicago Maroon, University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf7-03568, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

From our print archive: In remarks at Alumni Weekend in 1969, Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, AB’38, demonstrates the complexities of covering campus protest in the Vietnam era.

The subject most on our minds today is one about which, in many ways, we know least. I mean the confusing mass of facts and theories now labeled, in all our heads, as “the revolt of youth” or “the turmoil on the campus.”

I do not presume to offer an exhaustive catalogue of these matters, nor any grand philosophy illuminating them. Quite the contrary; the focus of my thoughts is the admitting and the analyzing of our ignorance. Why do we seem to know so little about unrest in our national life that disturbs so much? And more precisely still: What is the role of the press in this problem of universal education of all our people on what is actually happening in and to our educational institutions?

I might begin with a homely little personal anecdote on how not to communicate or to learn. It involves a friend of my youngest son and his rather distinguished preparatory school in Washington, DC.

The administration of this school recently decided—like so many others—to try something new to “reach” its rebellious students. It hit upon a kind of “sealed weekend” in the country, with teachers and rebels more or less locked together in dialogue to discover their conflicts. The dialogue, however, was indirect, for it was transmitted through a man who was hired as a “professional communicator.” The role of the “communicator” was to speed back and forth from the conclave of students to the conclave of teachers, all the while writing down the comments and retorts of each group and transmitting them—like a neutral messenger between opposing armies. Finally, he asked the boys—“Hey man”—he said—“can you think of a single word that applies both to what you think of the teachers and the teachers think of you?” With unmasked scorn, my son’s friend replied: “Hey man—paranoia.” This infuriated the “professional communicator,” who asked the boy what he meant by paranoia. Disdainfully, the young man explained: “You must know what paranoia means. It’s people who think other people are after them.”

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1533","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"351","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Katharine Graham on campus. (Photography by John Vail/Chicago Maroon, University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf7-00317-002, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

All this suggests, I think, the kind of sterile and synthetic “professional communication” that ends by enlightening nobody. And it may be a kind of model and lesson in how the press should not try to report, and explain to the nation, what is going on with our youth and our universities.

The National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence said something this week that we of the press ought to pay attention to. It said that the problems of colleges are made worse by a general lack of information. To quote the commission:

“On campus, large numbers of faculty and students often act on the basis of rumor or incomplete information. Alumni and the general public receive incomplete, often distorted accounts of campus developments. Campus authorities have the responsibility to see to it that a balanced picture is portrayed.”

And, I should add, the newspapers do, too.

But it is proving difficult for us to covet campus disorders. Our usual techniques have failed us. A journalist makes his living by understanding complex situations and making it easier for his readers to understand them too. We were formerly accustomed to sending a reporter to the scene of an earthquake, a strike, or a civil war one morning and demanding that he write about it that afternoon.

In the case of the colleges, and I might add in the case of Viet Nam too, this technique has failed us. As a leading education reporter said to me last week, “You can’t get the president’s statement at nine o’clock and trot over and get Mark Rudd’s at ten o’clock, print them both, and feel you’ve told what’s going on.”

To understand how completely our usual newspaper techniques have failed ns, it’s only necessary to look at how the wire services tend to cover college disorders. Each day during the last academic year, the wire service machines have tapped out a story about protests. The typical daily story starts with a description of the biggest and noisiest demonstration of the day. At the end of the story come ten or fifteen paragraphs telling what went on at ten or fifteen other campuses. It is the same format the wire services use to write about baseball—a description of the most exciting game and a sentence each on the others. I don’t mean to be too hard on the wire services—they are supposed to be covering hard news, and they are in fact also going in for very good background stories.

But there are three problems with telling the story of our universities way. First, while every baseball game is played according to the same rules, every college demonstration is not. You can’t even be certain what the sides are. Consider, for instance, the administration of California’s Berkeley campus. Is Chancellor Heyns an ally of Governor Reagan in the struggle over “the People’s Park,” or is the governor forcing the university to adopt a stance it actually opposes?

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1530","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"324","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Berkeley, May 24, 1969: During the People’s Park incident, National Guard troops prevented protesters from planting flowers, shrubs, or trees. (Photography by Kent Kanouse, CC BY-NC 2.0)

By running essentially the same story every day, newspapers have been committing the terrible injustice of equating every campus in the United States—of making our readers conceive that the same thing is happening at San Francisco State under S. I. Hayakawa and at Chicago under Edward Levi; that a protest about the teaching at all-black Howard University has something to do with protests about dormitory hours at Smith.

Second, it is safe to assume that anyone who reads stories about baseball games has the background necessary to understand them. It would be superfluous for a reporter to write that the game is played by nine men on a side. But no reporter can assume that his readers have this kind of background when he is discussing the troubled colleges. Consider the baffled way in which parents react to their own college-age children. The reporter who wants to tell large numbers of middle-aged Americans what is happening at colleges had better be patient and willing to listen for hours to a lot of people. And his newspaper had better provide him with more space than we usually do, because the conditions that lead to discontent at a college—any college—cannot be summarized in eight inches.

Third, in a baseball game you win or lose. All that counts, in the end, is the score. But in a university it is certain that there will be results more important than the number of men who demonstrate or get arrested, and it is not at all certain that the reader of a newspaper will learn about these results.

The problem, in short, is that we have been transfixed by the daily ritual of “confrontation” and may be ignoring far more important goings-on at our universities. The press is usually pretty good at finding out what is going on behind rituals. Theodore White showed us ten years ago, for instance, that the way to cover the ritual called a presidential campaign is not merely to write what the candidate says from the rostrum every day. But in writing about colleges we continued, at first, to rush from crisis to crisis, writing about non-negotiable demands and unyielding replies, buildings occupied and heads busted.

Once we get there, we may have trouble writing about these college students for the same reasons parents have trouble talking to children. They are talking about things we don’t want to hear about, or write about. For instance, sex is very much on their minds, but we haven’t yet reached the point of naming sexual subjects in American newspapers. Then, there is an important class element in this revolt at the universities; and we have ignored it, too, for the most part. It seems to be generally accepted that most white student protesters come from the economic upper or upper-middle classes. But I don’t think anyone has done enough work to find out the basis for the assumption.

John Maynard Keynes, writing in 1932, said that man’s worst long-range problem was not what he called the economic problem—how to feed and clothe himself. It was, Keynes said, what to do with himself once the economic problem had been solved. How do you live a life that satisfies you once you have enough money to live? It is not a question that the moneyed classes of previous generations have answered well. It should not surprise us that some young people are looking for the answer in drugs and some in sex. It should please us that so many have decided to devote their lives to altruistic service. It should interest us that the arts have proved attractive to so many. And it should concern us—and make us ask questions about ourselves as well as them-that some seem to find violence the answer to all problems.

Not only is there lack of agreement about major facts but also on minor but important ones. As Joseph Kraft pointed out in a column last month: “One of the central events in the academic civil war was the fight between black students at San Francisco State College and the tactical squad of the San Francisco police force. But a vice-president of the college and leading figure in the episode says, ‘To this day, I don’t know what transpired.’” Mr. Kraft goes on: “Another central event was the student occupation of the office of the president of Columbia last spring. Reporters present after the event witnessed the extensive damage and the university estimated the bill for repairs at more than $4,000. But the Cox Committee—a distinguished outside review board headed by Professor Archibald Cox of the Harvard Law school—reported that ‘there was no substantial vandalism.’”

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1531","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"324","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] Columbia, April 1968: A desktop in the Office of the President after the police bust. (Photography by Bonnie Freer, courtesy of Columbia College Today)

It is important to know, for instance, whether a professor whose views are unpopular with his local SDS chapter can teach his course without the threat of physical violence. We know that some students have· been calling on the University of California to fire Professor Arthur Jensen because he wrote that blacks, on the average, are born with a genetic deficit in what we call intelligence. We know that the chairman of the political science department at San Francisco State could not teach his course last winter because of disruptions. Are these sad cases the exception or the rule?

Then, while it is popular to say that violence has taken over on our campuses, who knows how much violence there has actually been? At some campuses in California, and at the City College of New York, buildings have been burnt down and bombs set off in connection with campus demonstrations. Has this happened at one or two colleges, or dozens? Was it done by students, or outsiders?

Finally, how much have the four years of college—and, for that matter, the years of graduate school—changed? It has been five years now since the Free Speech Movement took the streets at Berkeley. It is safe to say that no major college today is the same place it was in 1964. But how have they changed, each one of them? It is not enough to say that they all have black studies departments and their presidents all have ulcers. Will the life of the freshman that enters college this fall be any different, any better, because of all the sit-ins and demonstrations since then? The complaints we have heard so often—of shoddy teaching and irrelevant subjects, of teachers promoted for what they write rather than how they teach, of students treated with the impersonality of IBM punch cards—have any of these been answered?

One other question cannot be answered on the campus. It deals with the reaction, among working people and the legislators who represent them, to what the students are doing. The question is, how strong is that reaction? Or, to put it another way, how much time do the universities have?

I think it is essential that they be given as much time as possible. Prophecy is difficult, but if any one thing is sure about our colleges, it is that any attempt at repression of students by the government will have disastrous consequences.

We have seen in California almost a test-tube demonstration of the dangerous possibilities. Let me quote from a letter written by a senior at Berkeley to her mother in Washington, a friend of mine, at the height of last month’s dispute:

“Everyone’s afraid. I think our fear is most obvious in the frequent phone calls between friends, quiet gatherings here and there just to be with other people, expressing disbelief, anger, frustration. It has become quite obvious to everyone that we are very nearly completely helpless. There is much more to come. Ronald Reagan’s popularity increases (outside Berkeley) with every arrest.”

About this last point, at least, there is no doubt that she is right. As the students become more activist, the rest of the people react against them more fiercely. Last month in Berkeley policemen fired shotguns at a crowd of students, killing one. It is absolutely amazing that people seem to have reacted less strongly to this than they did to the carrying of guns at Cornell. Maybe this is so because we all are used to cops carrying guns and using them, but not to seeing college students carrying guns. Or maybe it was that singular photograph of the Cornell blacks carrying weapons. Parenthetically, I believe that pictures like this, or those two-minute film clips on TV, can sometimes mislead by conveying part of a story. For example, recently one of our white editors was by blacks at Howard University. We had a photo of the attack, and didn’t use it. The picture did not tell the whole story—what went on before and after the photo was taken. It failed to show the same editor being saved a few moments later by other blacks.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1532","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"527","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]] San Francisco State, 1968: Black and white fist illustration from the SF State College Strike Collection, artist unknown. (Image courtesy DIVA/San Francisco State University)

What happens in California has a tendency to repeat itself across the country. What happened at San Francisco State last winter and at Berkeley last month should have told us now and for all time that whatever difficulties students create for their colleges, those difficulties become a hundred times worse when they are compounded by political intervention.

When there’s an act of physical violence or law breaking, of course, outside force may become necessary. But we all know what this does to the University community, not the least of which is to ally the majority with the tiny minority of the far left.

As the violence commission has just said, we had better let our universities keep trying to solve these problems. Some will not be· able to. Protests will not die out overnight. But dealing with student protesters requires the wisdom, patience, care and subtlety of an Edward Levi, not the bludgeoning tactics of a Ronald Reagan.

We of the press have to begin answering these questions. I think by now we realize that we will have to change in order to do it. Some newspapermen realized this a long time ago. Here in Chicago, Larry Fanning, then editor of the Daily News, decided in 1965 that the universities were going to be an important continuing story, so he sent a reporter to live at the University of Illinois for three weeks. When the reporter turned in a forty-page story, Fanning printed it all.

We realize now that we have to be at universities before the trouble starts if we are going to understand what is happening at the barricades. The reporter who wrote that story for Fanning, Nick von Hoffman, now writes a column three days a week in The Washington Post. His formula for writing about college students—and, for that matter, southern whites, or Mayor Daley—is this: “The reporter can’t walk into a situation in a towering rage. You don’t have to agree with them, but when you disagree with them it’s on the basis of what they say, not of the frightened things going on in the reporter’s head. The reporter has to say: am I going to react, or am I going to learn and observe and see. Later you look, but first you try to understand.”

That is first-rate advice for reporters and for newspapers. I can’t help thinking it is good advice for everyone else as well.

This generation—so hostile to so much of its heritage—springs, in significant ways, most logically from that heritage. As a generation, it is no freak abortion. It has known a quite natural birth—from the world that it deplores.

I have asked my small array of questions. I have ventured no resounding answers, for I know none. I wish I could say, in the face of so much to confound us, with Robert Frost—“I am not confused. I’m just well mixed.” I cannot go that far.

I am certain only that we—and by we, I mean the press, the universities, the parents, the teachers-have at least as much homework to do as any body of students, if we are going to get matters somewhat straightened out in our heads and theirs. This means, above all, that we have to listen. It means that we have to listen most attentively when we hear what we like least. If we stuff our ears with cotton—and our heads with contempt—against all student outcries, we shall be the losers. And they may be the lost. If the dissidents talk a strange jargon, we still have to ask: What are they trying to say? If they sneer at old concepts of academic inquiry or academic freedom, we still must ask: How did they get this way? If their goals and purposes often seem to us unclear, we must remember: This does not make them unreal. And if the temperate and moderate dissenters get driven, suddenly or slowly, toward the most radical positions, we must quickly ask ourselves: Who and what drove them?

There are great freedoms at stake here. And I, think, I know whom their greatest enemies—on all sides—have been, are, and will continue to be. These enemies of freedom will be the dogmatic perfectionists. These are the demanders of all-or-nothing, the decriers of take-it-or-leave-it, the pretenders to the possession of all right and all truth, and the inquisitors—from left or right, young or old—hurling the ancient anathema that “error has no rights.” These enemies will be found on both sides of this dialogue between generations.

On the side of reaction, they will be satisfied with nothing but docility. They will confuse the teaching of students with the training of stallions. And they will think their very fury is holy. On the side of rebellion, they will be content with nothing short of unconditional surrender. They will confuse the launching of the new with the libeling of the old. For these fanatics of perfection, the Magna Carta is only the work of anti-Semites and the Declaration of Independence the work of slave-owners. And they, too, will think their very wrath is sacred. We may hope someday to bring some of these zealots to grasp the definition of holiness as “an intense desire not to have one’s own way.”

Katharine Graham, AB’38, was president of the Washington Post Company, publisher of The Washington Post and Newsweek. This article is adapted from her remarks to the communications dinner at the University of Chicago Alumni Weekend in June 1969, when she was named Communicator of the Year.