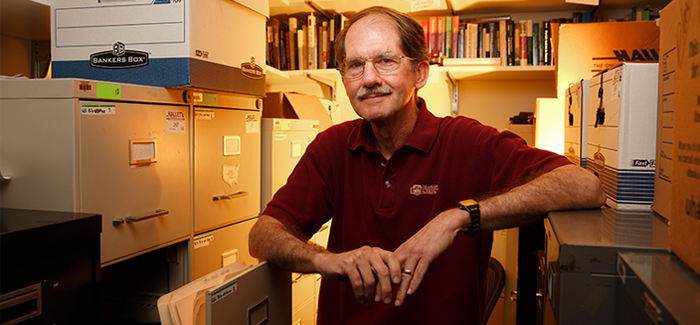

(Photography by Jason Smith)

GSS director Tom Smith, PhD’80, breaks down the numbers.

Forty years ago, Tom Smith, PhD’80, took a job at NORC to help make his way through grad school. All he knew was that it paid well: tuition plus a generous stipend. “By far the best support I could find,” he says. So in October 1973, at the start of his second year as a history PhD student studying early industrial Philadelphia, he began work at the NORC library on a fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health. A year later, a spot opened up at the still-fledgling General Social Survey, and he was given the assignment.

That’s when the hook set. Within two years, Smith was working full time for the GSS as associate study director, fitting in his dissertation when he could. In 1980, the year he finished his degree, Smith was named director of the GSS. He’s been there ever since, as not only the survey’s leader but its most public face. When the GSS speaks—to reporters, to scholars—it is usually in the voice of Tom Smith. Says GSS founder James A. Davis: “I’m the blue-sky idea man, but Tom does all the work. He’s incredibly smart, incredibly efficient. The whole thing would have fallen apart without him.”

In person, Smith is slight and angular, with wide, wire-rimmed glasses and a graying mustache. His shirt is rarely tucked in, his sleeves perpetually bunched at the elbow. His office windowsill is overrun with jade plants that have multiplied over the decades. But Smith exudes a casual, knowing precision. Speaking in the accent of his Pennsylvania upbringing—the swallowed syllables, the diminished consonants, the long “a” in “measure”—he has the diction and rhetoric of someone used to coming up with carefully worded questions. Always qualifying, contextualizing, clarifying one example with another, framing personal anecdotes in quantitative terms.

Smith grew up in State College, Pennsylvania, home of Penn State University, and in the 1950s his father gave up the family dry cleaning business to become a real estate broker. “Which was by far the smartest thing he ever did,” Smith says, “because now you’re talking about the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, when universities are expanding a lot. So there was a really strong real estate market in the local community there. And if anything, the dry cleaning market was going the opposite direction, because there was more ready-to-wear clothing, and men didn’t wear suits to the office every day anymore.” He looks down at his own wardrobe: cotton slacks and a loose corduroy button-up, with the sleeves bunched at the elbow. “As I can testify.”

Smith’s college years at Penn State coincided with the founding of a new academic field: quantitative social science history, an approach that uses numerical statistics like census records, tax records, and death records to analyze the lives of people and societies. In class, Smith read Stephan Thernstrom’s groundbreaking Poverty and Progress (Harvard University Press, 1964), a quantitative study of social mobility in 19th century Newburyport, Massachusetts. “I decided it was the best way to study and understand society,” Smith says. After earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history at Penn State, he came to UChicago in 1972 to study under historian Edward Cook, who had done similar quantitative studies of New England towns. Smith settled into a dissertation on the social structure of Philadelphia during the early industrial era, when traditional craftsmen’s shops were giving way to assembly lines, but before electric power and diesel turbines had taken over.

“The first part of the Industrial Revolution isn’t the application of power,” Smith says. “It’s the reorganization of businesses from small craftsman shops where you’ve got a master and maybe two journeymen” to factories with an owner and a bookkeeper and employees with narrow skills doing fractional work: nailing the heel of a shoe, stitching the sole, cutting the leather. “An interesting transformation was going on,” Smith says—the middle class shifting from blue collar to white collar as new professions materialized and old ones died out. “In the 1970s, this was vastly understudied.”

At the GSS, Smith’s quantitative turn of mind fit right in. “I always say that as a historian, I was interested in studying societal change,” he says. “And here I am, studying societal change—just about 170 years later than I originally planned.”