A band performs at an Austin, Texas, Juneteenth celebration in 1900. (PICA 05481, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

A historian sheds light on the document behind the newest federal holiday.

Forty years ago, Edward T. Cotham Jr., AM’76, began leading walking tours through historic Galveston, Texas. Each time he’d stop groups at the spot where the famous “Juneteenth order” was issued, he’d get quizzical looks. “June what?” people would ask.

Then a budding Civil War historian (who has since authored several books on Texas military history), Cotham was astounded by how few knew anything about that landmark day—June 19, 1865—when Union troops came ashore at Galveston Bay and freed the last major group of enslaved people in Confederate territory.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed two-and-a-half years earlier, freeing enslaved people in the “States and parts of States … in rebellion,” it wasn’t until Juneteenth that this promise was realized by military order. This was a day of independence celebrated by African Americans from the start, one just as important as the Fourth of July. Largely unnoticed outside of Black communities until this century, annual Juneteenth celebrations spread from Texas, where it officially became a state holiday in 1980, throughout the United States. The holiday has been hailed by some as the oldest continuous commemoration of emancipation in America, marked for more than 150 years by parades, pageants, and picnics.

“I thought, ‘Someday someone needs to write a scholarly book about the history behind this event,’” says Cotham, who is chief investment officer and emeritus board member at the Terry Foundation, the largest private scholarship provider in Texas, alongside his authorship of historical works. Four decades and much painstaking archival research later, his Juneteenth: The Story Behind the Celebration (Texas A&M Press, 2021) landed last summer, just weeks before President Joe Biden declared June 19 a federal holiday (Cotham swears the timing was sheer luck).

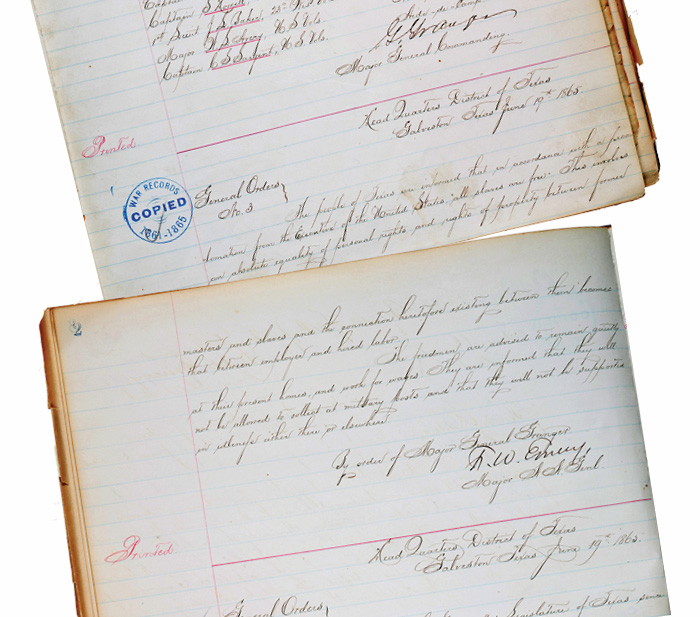

Much of Cotham’s research centers around the document at the heart of the holiday—the understatedly titled “General Orders No. 3,” embraced by formerly enslaved people as their “freedom paper.” Although penned in elegant cursive, the order’s four sentences were strung together in a way that baffled him. Its first line contained a rousing nod to the Emancipation Proclamation: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, ‘all slaves are free,’” it declared. Yet that liberatory language was sharply contradicted in the last two lines, which admonish the newly emancipated to stay put “quietly” and keep working for their former masters as hired laborers.

“That was always the great puzzle to me, how it came to be that we cele-brated and gave parades for this order that had two almost conflicting themes,” Cotham says. “The first sentence says you’re free, the last two sentences say you’re free to stay where you are.”

The puzzle didn’t end there. The document’s second sentence calls for “an absolute equality of personal rights” between former masters and those they had enslaved. “That’s in many ways the most elaborate and beautiful language in the whole document,” Cotham says. But it was not the stuff of military orders.

Finding out who authored it was Cotham’s most surprising discovery. A staff officer named F. W. Emery had been tapped by Union Army top brass to sign and administer the order on behalf of his superior, Major General Gordon Granger (whom Army leadership disliked and mistrusted). The 29-year-old editor of a crusading antislavery newspaper, Emery had fought alongside John Brown Jr., son of the martyred abolitionist. The young idealist took the opportunity to make his mark, and Cotham says he is “100 percent convinced” Emery wrote that line and slipped it into the order. “He just happened to be on the scene to write that order in a way that would last through the ages and in a very specific way define freedom.”

That revelation clarified some details about the way Juneteenth has been popularly understood. Because Granger’s name appears on the Juneteenth order, he has been incorrectly portrayed as a champion of abolition who not only authored the document but read it from a balcony to the surprise and awe of his enslaved listeners. Cotham contends that none of that is true. Granger had a questionable record when it came to the enslaved population, probably knew little about the order’s content, and would not have been pegged as a civil rights icon by those who knew him.

In addition, the order was not read as a public address but rather disseminated on handbills and reported widely in Texas newspapers. It was read to enslaved people by their former masters, however. In archival interviews from the 1920s and ’30s, many formerly enslaved people remembered that they were told, “You are as free as I am,” a sort of translation of Emery’s words. That repetition took Cotham aback. “I said, my goodness, this is an echo of 150-year-old language that was read to [them] that they remembered all the rest of their lives.”

But Cotham points out, interestingly, that not all enslaved people were shocked by General Orders No. 3. “We have evidence that there was this very informal network of communication between enslaved people all over the South and certainly through Texas,” he says. Some formerly enslaved people even reported knowing about the Emancipation Proclamation before their masters did. As a result, Cotham says, “they were not surprised by emancipation and expected it to come.”

With Juneteenth finally recognized by the US government—156 years after African Americans first claimed it as their Freedom Day—Cotham hopes that important truths about it will emerge. The order likely resulted in immediate freedom for more people than any other document issued during the Civil War, but as he reminds us in Juneteenth, the liberation of enslaved African Americans didn’t happen simply through documents or speeches “but because of their own struggles and the struggles of people who fought to free them.”