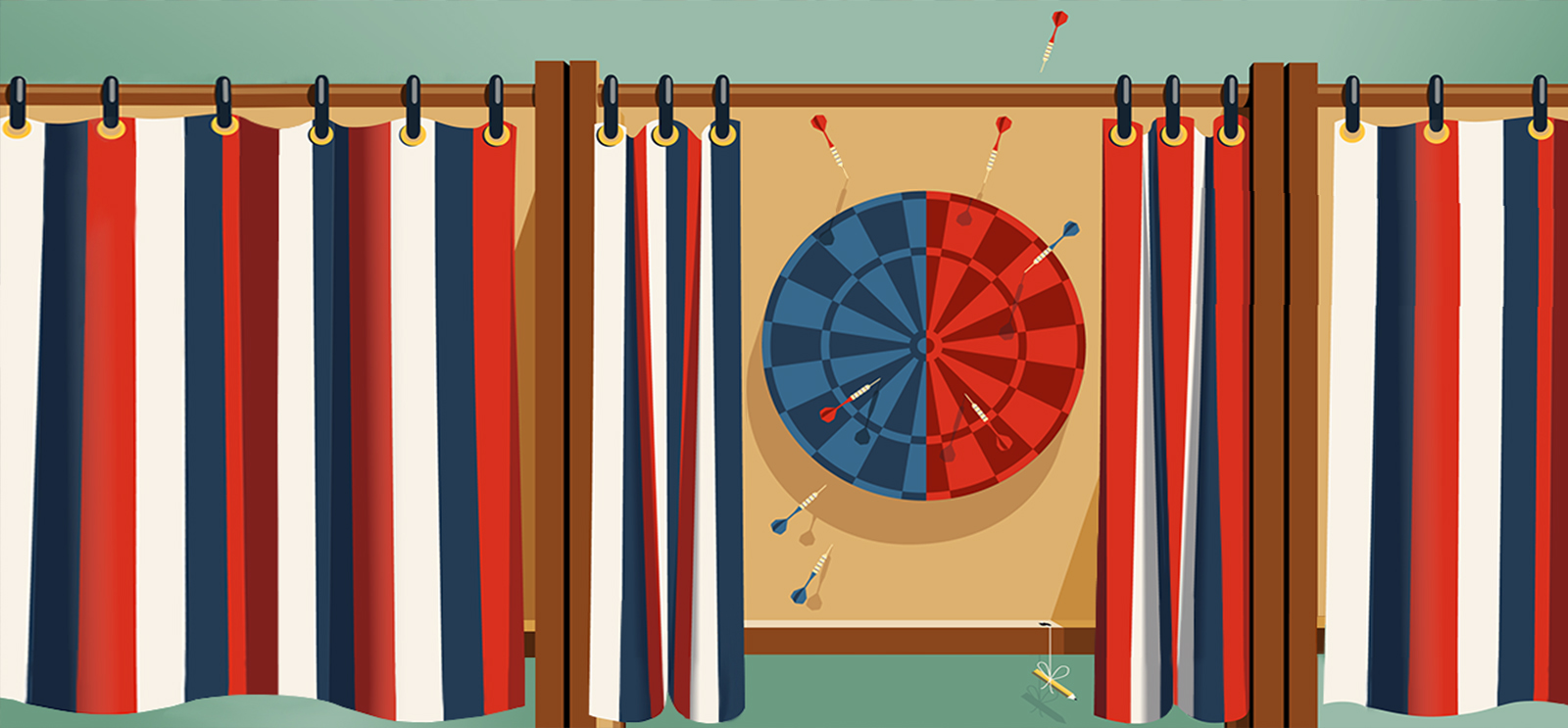

(Illustration by John W. Tomac)

A start‑up founded by three alumni helps voters think beyond the presidential race.

Running for office is no small feat. There are hands to shake, funds to raise, questionnaires to fill out, platforms to build, endorsements to earn, and babies to kiss. But candidates for the Board of Commissioners of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago carry an added burden: many voters have no idea who they are or what the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District does.

Todd Connor, MBA’07, was prepared for that less-than-glamorous reality when he ran for water reclamation district commissioner in the 2010 Democratic primary. “You know, I had heard these things, like ‘It’s really hard to win’ or ‘It’s all about ballot position,’ but I sort of didn’t believe it,” Connor says. “And I thought, ‘Well, it’s going to be different for me.’”

“And then,” he says matter-of-factly, “I ran and I lost.”

Longtime Chicago political columnist Russ Stewart once wrote that the MWRD race comes down to “the uninformed picking the unknown.”

That’s true in many local races across the country. Part of the challenge for voters, according to John Mark Hansen, is that so many American government offices are filled by election rather than appointment. Between national, state, municipal, and special district elections, “you could spend all of your time voting in the US,” says Hansen, the Charles L. Hutchinson Distinguished Service Professor in political science and the College. As a nation, he argues, we expect a lot from our voters.

And American voters often don’t know enough about the candidates to deliver on these expectations. For the majority of the electorate, “the information they have is information that they receive passively,” Hansen says. “It’s information that they receive from the media, it’s information they receive in conversations with people, it’s stuff that they just hear.” By October in a presidential election year, he says, many voters have a decent sense of where major-party candidates in national and statewide elections stand on key issues.

But down the ticket? Not so much. Down-ballot races rarely receive significant media coverage, leaving it to voters to actively seek out information on the candidates. Connor isn’t joking when he says it’s probably easier to run for governor of Iowa than for water reclamation district commissioner in Cook County.

The staggering number of elected officials in the United States (about half a million, according to American University political scientist Jennifer Lawless) and the large number of decisions voters have to make in any given cycle, has important effects on voter participation. Not only is American voter turnout extraordinarily low, but many voters “roll off”—that is, leave blanks on their ballot—or guess.

In 2012, Alex Niemczewski, AB’09, was one of those voters who guessed. She walked into the voting booth, confidently cast her ballot in the presidential race, and quickly got lost in a thicket of judicial retention races, school board candidates, and ballot measures. “There were offices where I didn’t know what that person did or could do. ... There were names I had never heard of,” she says.

For her next election, Niemczewski wanted to prepare but felt overwhelmed by the task. “I tried to do the research myself,” she says, “and it was just so time consuming, and it was so hard to find the information.” There was no single resource that provided meaningful information about every candidate on her ballot—so she decided to build one.

This is the origin story of BallotReady, the website Niemczewski founded in 2014 with Aviva Rosman, AB’10, MPP’16, and Sebastian Ellefson, AB’03. Sitting in a sunny nook in the Chicago Innovation Exchange, BallotReady’s current home, Niemczewski explains the project that has consumed her for the past two years: essentially, BallotReady does your civics homework for you, providing free, nonpartisan, easy-to-access information about every candidate and every issue on your particular ballot.

BallotReady started small, launching with a test run in Chicago’s April 2015 mayoral runoff election on a budget of just $180. A month later, they won the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation’s John Edwardson, MBA’72, Social New Venture Challenge, and this June they received a major infusion of capital from the UChicago Innovation Fund. They’ve also gotten help from the Institute of Politics, where this summer they are entrepreneurs in residence. The team originally planned to cover seven states in the November general election, but they’ve upped that number to 25.

Niemczewski is soft-spoken, thoughtful, and appears remarkably serene for someone who is working “every waking minute” on BallotReady. Even as an undergraduate studying philosophy, she knew she wanted to found a start‑up someday. Still, there’s something pleasantly old-school in the way she talks about BallotReady. She does not use the word “disrupt” even once.

Niemczewski didn’t have a particular interest in politics before starting BallotReady, but her cofounders Rosman and Ellefson are, she says, “obsessed with elections.” Growing up in Boston, Rosman accompanied her father to New Hampshire during presidential primary season and once flew to Florida to canvass for a candidate. She’s been a candidate herself: Rosman won election to her neighborhood’s local school council in 2014, not long before BallotReady was founded. Niemczewski and Rosman recruited Ellefson, whom they knew to be a political aficionado, that summer. Over drinks at Jimmy’s, the trio settled on the name “BallotReady.”

Users provide BallotReady with their home address, which is used to generate a digital copy of their particular ballot. They can compare candidates by selecting an issue (“energy/environment,” “foreign policy,” “immigration”—the list varies by office), quickly review candidate experience and endorsements, and “save” candidates as they go. A bar at the side of the screen shows voters their progress through the ballot, which feels “so satisfying,” Niemczewski says. On election day, users can print out a list of their candidate selections or access it on a smartphone from the mobile-friendly BallotReady website.

BallotReady’s information is assembled by an army of political science student interns at colleges and universities nationwide. During “civic hackathons,” they pull information from candidate websites, local news agencies, and endorsing organizations. Niemczewski describes the process as “structured crowdsourcing. ... They’re doing very specific tasks, like, ‘Here’s a candidate’s website, tell us where they went to college.’” Each task is repeated by multiple people so it can be verified by BallotReady staff before it goes live on the site. “The most important thing for us is that voters know that we are a trustworthy source,” Rosman told Governing magazine in March.

By spending time on BallotReady, users can develop a stronger understanding of how their government works, Niemczewski says. “You may not know the job of water reclamation commissioner, but you could see, oh, these are three or six different ideas for how to tackle this problem. And that can help you start to piece together something of an opinion and an idea of how these things work.”

While talking to voters about BallotReady, Niemczewski learned just how common her experience in the voting booth was. “Literally everyone has admitted to guessing,” she says. “We talked to political science professors here [and] at other universities who admit to guessing—and political reporters.”

It’s so frequent, in fact, that a robust body of research is devoted to understanding the ways US voters skip and guess their way through the ballot.

A University of California, Irvine, study found that only about half of voters in a 1994 California election completed their entire ballot, avoiding races where they did not feel informed. Some voters do take a stab at unfamiliar contests, using various heuristics to guide their decisions. A common one is political party. Even when you know little about a particular race, you’ll probably vote for your preferred party’s candidate.

In a primary or a nonpartisan election, though, you might use other cues. In low-information races, a 1998 University of California, Los Angeles, study found, liberal voters favored female candidates, guided by the belief that women in politics tend to be left leaning. (Younger voters were more likely to pick female candidates as well.)

Historically, ethnic voting has been a powerful electoral force. Chicago lore has it that some candidates changed their last names to sound more Irish, believing that Irish ancestry conferred an advantage on Chicago candidates. There’s some truth to that old chestnut. In judicial retention races in Cook County from 1982 to 2002, Irish names offered a small but statistically significant boost of 1.5 percentage points, according to a 2005 study by legal research analyst Albert Klumpp, AB’85. Of course, what counts as a good “ballot name” depends on where you live and the office you’re seeking. Sam Houston, aspiring attorney general of Texas in 2014? That’s a good ballot name.

The order of names matters too. Being listed first increases a candidate’s chance of winning by about five percentage points, according to a study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Marc Meredith and Northwestern’s Yuval Salant. In some cases, the “first-position effect” was enough to change the outcome of a close race. “Our results imply that a non-negligible portion of local governmental policies is likely being set by individuals elected because of their ballot position,” Meredith and Salant concluded. Other studies have shown the name-order effect is especially strong in primaries and low-information elections.

For many voters in Cook County, the race for Metropolitan Water Reclamation District commissioner is about as low-information as it gets. Yet the poorly understood agency does essential work: the MWRD is responsible for sewage treatment and flood prevention over a nearly 900‑square‑mile service area that includes the city of Chicago and 125 suburban communities. Its seven water reclamation plants and 22 pumping stations treat more than 1.4 billion gallons of wastewater each day, and its nine-member board manages an annual budget of roughly $1.3 billion. In heavily Democratic Cook County, the Democratic primary is the contest—the last time a Republican won a spot on the MWRD board was in 1972.

MWRD candidate Connor grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. He joined the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps while he was an undergraduate at Northwestern. After graduating, he served two tours aboard the USS Bunker Hill. Connor was responsible for ensuring the missile cruiser’s compliance with environmental policy, so he knows a lot about water conservation. It frustrated him when he attended a 2009 MWRD board meeting and heard the commissioners spend more time honoring an Eagle Scout than discussing a bond deal. By running, he thought he could make a difference.

As part of his seven-point plan to improve the MWRD, Connor wrote about the need to reform the board’s procurement rules and the importance of new waterway disinfection policies. He also wanted to tighten the board’s ethics rules; as it stood, a commissioner could accept unlimited contributions from construction firms to whom they later awarded contracts.

Connor has the ability to sound passionate about the traditionally unsexy subject of water management. “This is a board that’s managing a multibillion-dollar budget. We ought to have some folks in there who can bring some business acumen and think differently about the problems that we’re facing,” he says. “I thought it was a great place to have an impact.”

In his campaign, Connor followed the model of his mentor Debra Shore, a reform-minded and conservation-oriented MWRD commissioner who won her spot on the board in 2006. Like Connor, Shore wasn’t endorsed by the Cook County Democratic Party—traditionally an important, though not make-or-break, endorsement—but ran a spirited campaign that united left-leaning groups across the county. She finished first in the primary with more than 200,000 votes. Connor did about as well as any political newcomer could, earning the support of key organizations, including the Illinois Sierra Club, and established political figures, such as then-alderman Toni Preckwinkle, AB’69, MAT’77; state representative Barbara Flynn Currie, LAB’58, AB’68, AM’73; state senator Kwame Raoul, LAB’82; and US representative Jan Schakowsky.

Running on a platform of environmental sustainability and government transparency (his slogan was “clean water, clean government”), Connor raised nearly $100,000—more than any other nonincumbent MWRD candidate and the second-highest total in his Democratic primary.

In a glowing endorsement, the Chicago Tribune described Connor as “exceptionally well-versed in MWRD and water policy issues” and said his background as a naval officer, Chicago Booth alumnus, and management consultant with Booz Allen Hamilton gave him “a superb skills set for a seat on this board.” The Chicago Sun-Times and Daily Herald endorsed him too.

With key endorsements and a well-funded and smoothly run campaign, Connor seemed at least a plausible contender for one of the board’s three open spots. So it was surprising, even a little dispiriting, to learn he finished fifth of nine candidates, with 10.66 percent of the vote. Turnout was abysmal, with just 26 percent of voters showing up to the polls. If everyone who turned out had voted for three candidates, there would have been about 1.7 million ballots cast in the MWRD race. The combined tally was about 1.2 million.

There are many ways to interpret the election’s outcome—perhaps voters simply found other candidates more qualified or disagreed with Connor’s policies. But Connor has a theory that at least one other factor played a role. In November 2009, with his campaign going strong, he learned his lottery-assigned position on the ballot: second from the bottom. He knew this was bad news, though he didn’t understand quite how bad until he called Shore, who promptly gave Connor her condolences. She told him to look back at previous election results for the water district commissioner race. While it’s not impossible to win from a bad ballot position, it’s also true the second-from-last spot hasn’t been kind to water reclamation board candidates. From 2006 to 2016, not a single Democratic contender has won from that ballot position. In the end, it’s entirely possible the luck of the draw doomed him, or prevented him from doing better.

“I still don’t want to believe that about our democracy, but of course, I know it to be true that people go and vote for these offices and they just don’t know who’s running,” Connor reflects. So they skip, or they guess.

For all the light and heat of presidential campaigns, what’s happening at the state and local level can affect your life just as much, if not more. Officials whose names you may not know make decisions about your property taxes, the school your child attends, the bus you take to work each day, the safety of the water you drink. “In Flint, it’s the water. In Illinois, it’s mental health clinics, it’s policing, the budget,” Niemczewski says.

When talking to voters about BallotReady, she learned many voters are ashamed of their ignorance of local politics. “They know local elections matter,” she says. “They feel a sense of guilt.” Still, one thing can be said of these tail-between-the-legs citizens who are voting for women, or the first candidate listed, or Seamus O’Neill, or leaving blanks: at least they’re showing up to the polls.

At the heart of BallotReady is a hopeful belief that people want to and will do the work of educating themselves—if you make it easy for them. Early signs are promising: the day before the March Illinois primary, BallotReady’s site went viral on Reddit and Facebook. About 64,000 people, says Niemczewski, used the site for that election.

Niemczewski’s grandest ambition is that BallotReady will someday be used for “every candidate in every race in every election in every democracy.” She also hopes it can be expanded to keep voters engaged in politics between elections.

For his part, Connor loves the idea of BallotReady, and he’s met with Niemczewski to offer his insight, both as a former candidate and as a fellow entrepreneur. If BallotReady or something like it had been available when he ran, he thinks it would have helped, “absolutely.”

The work he’s doing today as CEO of Bunker Labs, a start‑up incubator for veterans, suits him well, he says. “There’s a lot of freedom to move really fast, which I like. I feel like I’ve always moved at private-sector speed but want to have public-sector impact.”

And, no, he hasn’t ruled out the idea of running for office again.