Researchers believe that point-in-time studies like this one on January 31, 2013, in Washington, DC, may miss people who sleep in hard-to-find locations or deliberately evade being counted. (Photography by Robert Turtil, US Department of Veterans Affairs)

A Chapin Hall study finds higher rates of youth homelessness than previously reported.

The homeless are among society’s most vulnerable populations, especially homeless youth. Compared to young people with stable housing, they are at greater risk of a host of dangers: physical and mental health problems, violence, early pregnancy, substance use, and early death.

But a lack of reliable, consistent data on youth homelessness has stood in the way of a full understanding of the problem and of meaningful remedies.

To address that challenge, a team including researchers from Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago surveyed some 26,000 individuals by phone and conducted 150 more detailed follow-up interviews. Their findings were published this January in the Journal of Adolescent Health and are part of Voices of Youth Count, a national research initiative on youth homelessness led by Chapin Hall.

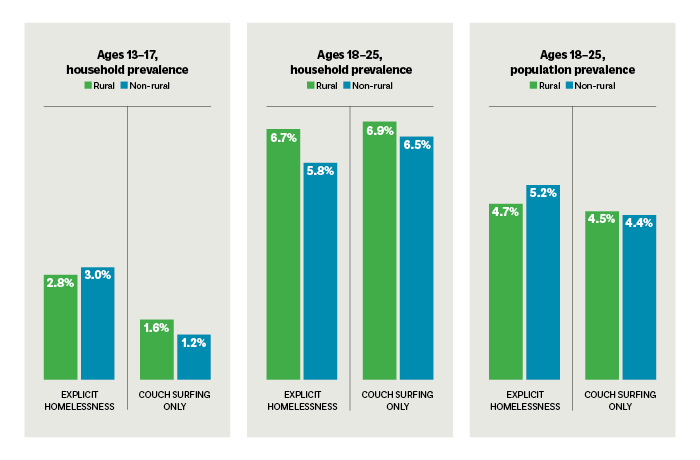

The researchers studied adolescents aged 13–17 and young adults aged 18–25. They distinguished between “explicit youth homelessness,” such as sleeping rough, running away, or being asked to leave home, and “couch surfing”—that is, staying at the residences of acquaintances in the absence of a safe, stable home.

As the graph above depicts, the study found that youth homeless rates were consistent across urban and rural settings, and higher for the older age group. It showed that several factors increased the risk of oneself or a member of one’s household experiencing homelessness: being an unmarried parent, LGBT, African American, without a high school diploma, unemployed, or earning less than $24,000 per household.

Compared to previous studies, such as the 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, which counted people living on the street or in shelters on a particular night in January, the researchers believe their method was less likely to miss people—for instance, those sleeping in hard-to-find places or deliberately evading being counted. Those point-in-time studies, when converted to national prevalence rates, yield sharply lower estimates of US homelessness. The higher rates their study revealed, the authors write, show the problem is of “a scale that necessitates greater coordination and resourcing of multiple systems and programs” to tackle it effectively.