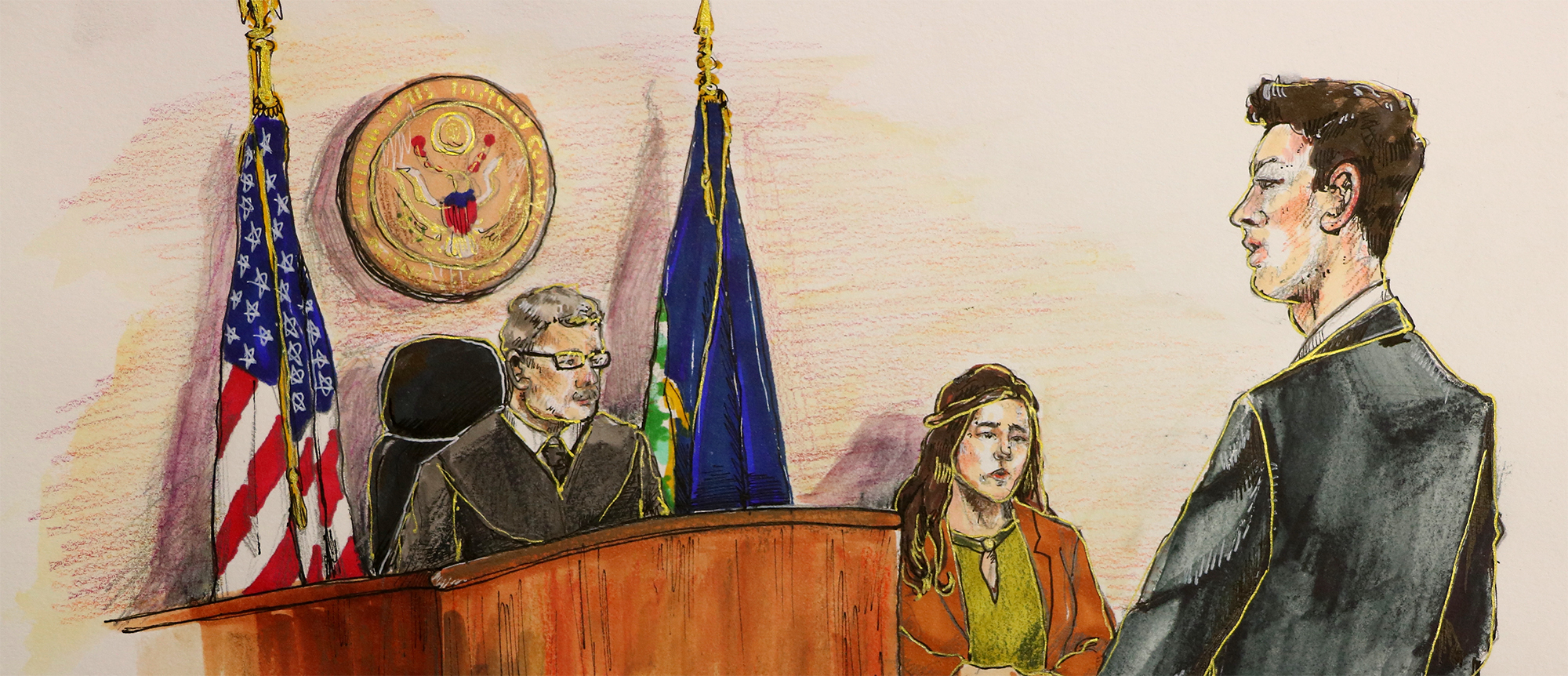

The National High School Mock Trial Championship includes a competition for courtroom artists. This drawing by Adeline Wang won first place in 2017. (Illustration by Adeline Wang, photo © Shawn P Yancy & NHSMTC Inc.)

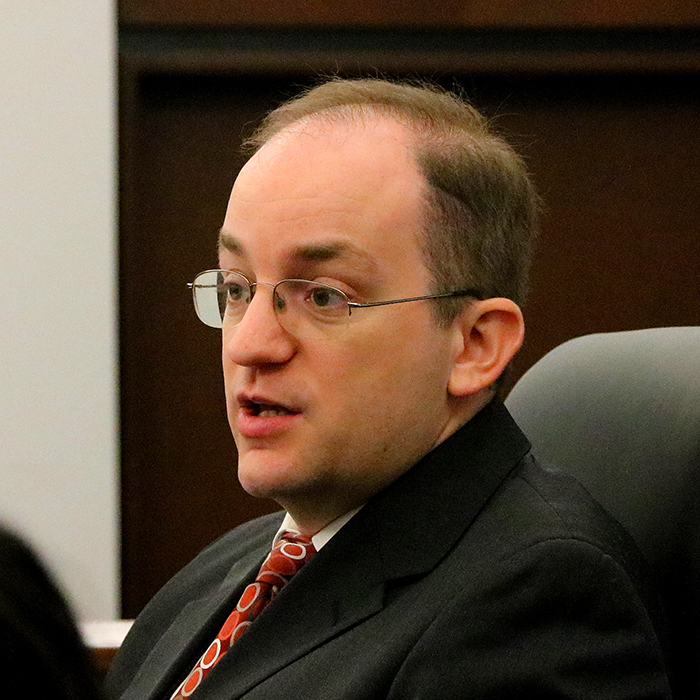

Paul Kaufman, AB’00, did mock trial in high school. Now he runs the show.

In May 2020 Paul Kaufman, AB’00, an assistant US attorney in Pennsylvania who prosecutes cases of fraud against the government, was elected chair of the National High School Mock Trial Championship. The academic competition is organized by an all-volunteer board that Kaufman now leads. Teams from more than 40 states, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and South Korea—which participates through a partnership with Yale—compete to show their legal skills and understanding in a real courtroom.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How does mock trial work?

Between six and eight students are put on each side of a fictional trial. In most places, you have three student attorneys and three who pretend to be the witnesses.

The trial proceeds just like in real court. There’s preliminary stuff with a judge and opening statements. Then you have direct examinations of witnesses and cross-examinations by the other team. Flip sides: the defense puts on its three witnesses and the prosecution or plaintiff cross-examines them. Then you have closing arguments, and there are objections under a slightly stripped-down version of the federal rules of evidence.

The students are assessed—typically by attorneys, paralegals, or occasionally law students—on each aspect, including the witness performances. These are judged as a sort of theater, but also on the ability to convey the important points for their team and perhaps resist cross-examination.

You did mock trial yourself in high school. Was that formative?

Thirty years later, I’m essentially on the same path that I stepped onto as a freshman.

So in the College, you were already on a legal track?

I entered UChicago as an East Asian languages and civilizations major, but Mandarin whupped my butt. I have a degree in American history, which was essentially legal history. When I was a third-year, I think there were seven tenure-track positions in American history in the country. I was like, well, there’s a hell of a lot more lawyers than that.

What are your specific responsibilities at the mock trial organization?

I got a reputation early on for writing cases. I’ve authored four national cases: one of civil battery (excessive force with a Taser), one of wrongful death by poisoning, one of solicitation of homicide (murder for hire), and one allegorically based on the Boston Massacre. But my formal duties as chair are running the meetings, signing contracts, and trying to recruit a host since our championship travels every year to a different city.

How has the pandemic affected the competition?

I took over right after we had canceled nationals. Then we had virtual nationals in Evansville, Indiana, in May 2021. The likelihood that we were going to be able to pull off an in-person competition in courthouses that were closed was pretty low.

Mock trials are held in real courthouses?

Oh yeah. We try to be in a courthouse for every round that we can. Some of the rooms are palatial, ceremonial courtrooms that hold 150 people, and some are landlord-tenant hearing rooms that maybe hold 40. But the experience is of being in a real courtroom.

What has impressed you most over the years?

When a student really kills it on the witness stand. You lose the high school student and now you’re talking to a neurologist.

A more humorous example: two years ago, somebody got up to close and then fainted—you know, dehydration, kids, adrenaline, the whole thing. Thankfully, one of our jurors got around the jury box and managed to catch her. She was completely mortified but wanted to start again immediately. We were like, no, no, take a minute, take a deep breath, have a little water.

What was your College experience like?

My biggest activity was being the president of the Inter-House Council. I learned how to chair a meeting, how to coordinate people with different ideas. That certainly comes up when you put 10 or 15 attorneys or legal educators in a room and try to get them to agree on anything.

But my overwhelming memories of UChicago are of the joy of engaging on an intellectual level, whether that’s 2 a.m. dorm room conversations about Aristotle or the Bulls or the way prior bad act evidence can or can’t be admitted.

What do you do as an assistant US attorney?

Fraud prosecution, usually in health care and defense procurement. If you think about Medicare, Medicaid, and defense, they’re ripe places for people to try to color outside the lines.

I also teach courses on health care fraud at Penn and Temple. I am good at teaching subjects that people find intimidating or boring. Maybe that ties into my Chicago experiences too. My bio sequence, Origins of Cancer, was a beautiful con job because they were just teaching you cell biology. You did eight or nine weeks of cell biology and then they were like, oh, and by the way, here’s how it all gets screwed up.

What lesson from the College has stuck with you?

I have gratitude to UChicago for introducing me to Cicero. We talk a lot about rights in this country, but Cicero argues that every right is related to a corresponding duty. You have the right to vote, but you have a duty to think through what that vote means. In order to be a good citizen, you have to work.