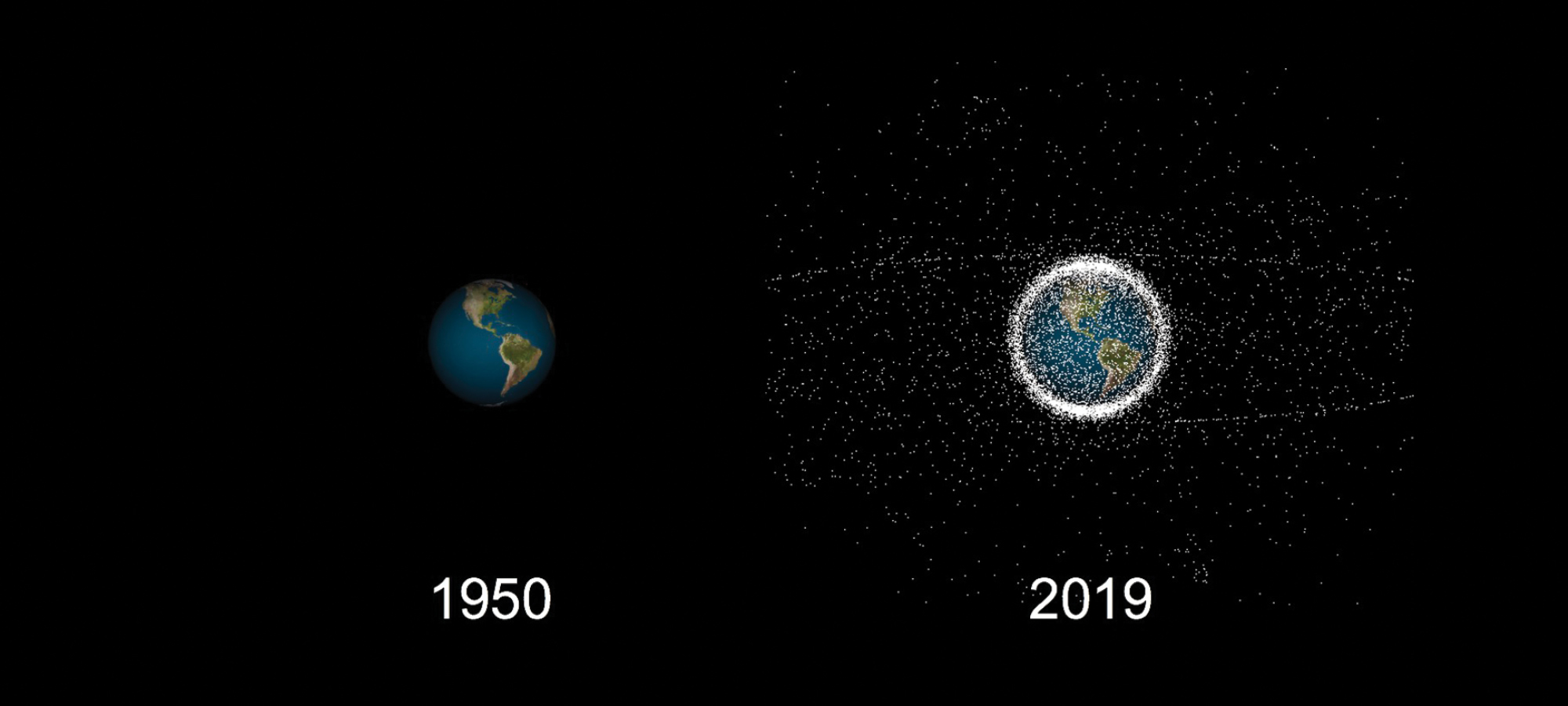

Traffic jam: Earth’s orbits are home to satellites, telescopes, space stations—and 100 million pieces of space trash. Dave Fischer, AB’87, is working to clean up these high-altitude highways. (Image courtesy Astroscale)

Dave Fischer, AB’87, helps the space industry become more sustainable.

Imagine you’re on a road trip and you run out of gas, pop a tire, or break down. You might call roadside assistance to get refueled, repaired, or towed away. But what if everyone left their broken-down cars on the road? Or abandoned their vehicles once they reached their destinations?

This hypothetical is reality on Earth’s orbital highways. Satellites, telescopes, and space stations transit amid 100 million pieces of human-made debris—paint flecks, screws, defunct satellites, bus-sized rocket bodies—traveling around 16,000 miles per hour. The Department of Defense tracks roughly 23,000 pieces larger than a softball to predict impending conjunctions—spacespeak for collisions—and to advise functional satellite operators to move their equipment out of the way. Orbital collisions can destroy hardware, end missions prematurely, and create even more debris.

Space development is “a trillion-dollar economy,” says Dave Fischer, AB’87, and the industry exacerbates the debris problem while also suffering from it. Astroscale, where Fischer is vice president of business development and advanced systems, hopes to declutter space by offering on-orbit services and debris removal.

There are several types of orbits; two are most relevant to Astroscale’s services. Satellites in geostationary orbit (GEO) travel about 36,000 kilometers above and along the equator. They move at the same rate as Earth’s rotation, keeping them in a relatively fixed position, which allows satellite television, for instance, to transmit with few interruptions. More accessible—and therefore far more crowded—is low-Earth orbit (LEO), located 160–1,000 kilometers above Earth. The Hubble Space Telescope and the International Space Station travel in LEO.

Nonstationary satellites in low-Earth orbit aren’t required to follow specific paths, so LEO offers more flexibility and space to maneuver. But those satellites circle Earth in about 90 minutes, too quickly to easily track from the ground. Many companies compensate by using constellations—networks of satellites that work together and form a web around the planet. An estimated tens of thousands more satellites will be launched into LEO in the next 10 years.

“Right now we’re operating under rules that were written in the 1970s,” says Fischer. “If you launch something into low-Earth orbit, it has to deorbit within 25 years.” But today there are more than 6,500 satellites on orbit, nearly half of which are dead. This level of development without disposal is unsustainable.

Headquartered in Japan, Astroscale was founded in 2013 with a focus on debris removal. Fischer, who has worked in the space sphere his entire career—starting at Yerkes Observatory as an undergrad, then building ground-based observatories in Antarctica, and finally transitioning to aerospace—joined Astroscale’s US team in 2020.

By signing on with Astroscale, Fischer “failed at retirement.” UChicago alumni, he says, might have “a little more energy than is good for us.” In fact, this year he’s turned some of that energy toward creating the University of Chicago Space Network, a networking and mentorship group for alumni in the space industry.

By the time Fischer joined Astroscale’s Denver office, the company had expanded beyond developing tools for debris removal. Their mission now includes technologies that provide end-of-life services (preparation for eventual removal of dead satellites) and satellite life-extension assistance (restoration, refueling, and repair).

How space junk would be removed depends on its location. In LEO a service vehicle would grab a piece of debris and deorbit it by dragging the object low enough for it to burn up in the atmosphere. For GEO debris, deorbiting wouldn’t be practical; those objects would be moved to a graveyard orbit. But at some point, those graveyards will need to be decluttered as well.

Astroscale’s debris removal and end-of-life services are related. For existing debris, the company’s servicer would rendezvous with the object and inspect it for a structurally sound place to dock. “None of the satellites that are in GEO today were launched with the intent that they would be docked with,” says Fischer. But almost all were built with a payload adapter ring that connects the spacecraft to the rocket, which the service vehicle’s grappling arms can grab. For future debris, the end-of-life program makes removal easier by preparing satellites before launch with, for example, a magnetic docking plate that Astroscale developed with Colorado company Altius. (Millimeter-sized litter also poses considerable danger but requires different solutions. Big nets or even sticky satellites have been proposed.)

The final service—life extension—is meant to slow the space debris problem. “Satellites are built to last,” says Fischer, but they often run out of fuel around 15 years after launch. “This is the value proposition to commercial operators: your satellite is still working. You don’t need to retire it.” Astroscale hopes to send a service vehicle to drained or damaged satellites to refuel them or make repairs.

A few other organizations are working on the sustainability goals at the heart of Astroscale’s mission. Swiss start-up ClearSpace plans to launch a debris removal mission by 2025, and American aerospace conglomerate Northrop Grumman docked a life extension vehicle to a depleted satellite in 2020. Astroscale has a service vehicle on orbit as well: a refrigerator-sized demonstration vehicle launched in March successfully exhibited its ability to dock with a smaller craft, send it tumbling away, and then retrieve it.

Astroscale’s mission transcends its services. “We’re trying to help drive policy changes that say responsible behavior looks like this,” Fischer says. Rewards and penalties influence behavior, he adds, but setting a good example works too. For instance, anyone can use the docking plate Astroscale codesigned to deorbit a satellite. You might think no one would act conscientiously out of the “goodness of their heart,” he says, but Astroscale has had companies voluntarily request help making their business sustainable. The hope is that “everybody sees space as global commons” and collaborates with a shared vision of the future. That means offering assistance to those who need a boost.