Ceraurus trilobite, cast in bronze. (All images courtesy D. Allan Drummond unless otherwise noted.)

D. Allan Drummond resurrects trilobites using modern and ancient techniques.

“Based on the fossil record, about 521 million years ago trilobites exploded out of the Cambrian Period and onto the scene. These three-lobed segmented arthropods swarmed the seas until an extinction event 250 million years ago wiped them out, along with 90–96 percent of all marine species.

Trilobite fossils have been found on every continent, making them fairly recognizable. But because they are embedded within rock, half of these creaturesʼ bodies remains hidden. As a kid, artist and UChicago biochemist D. Allan Drummond really wanted to flip them over and see what was underneath. He found this limitation “completely unsatisfying.”

Now he brings trilobites back to life as sculptures you can pick up, roll around, and study from all angles. Drummond designs the trilobites meticulously, 3-D prints individual pieces, then assembles them after theyʼve been cast in bronze using a lost-wax technique.

“Trilobites are distinguished by their incredible morphology,” he says, “particularly on top—some have wild spines, some have wraparound eyes. Their undersides have legs, gills, and antennae.” To recreate trilobites with the highest degree of accuracy, he studied photographs and papers going back a century—in particular work that examined rare soft-tissue-preserving fossils to characterize their less durable bits.

“This one has a little secret,” says Drummond, pulling out the antennae of his Cryptolithus bellulus sculpture before separating the body to reveal its digestive and nervous system within. Itʼs all held together with magnets.

Trilobites aren’t Drummond’s only subjects. In his lab he studies how cells respond to stress, and the sculpture most closely related to that work is a peanut-shaped figure that, when flipped over, reveals its budding yeast identity, complete with tiny organelles.

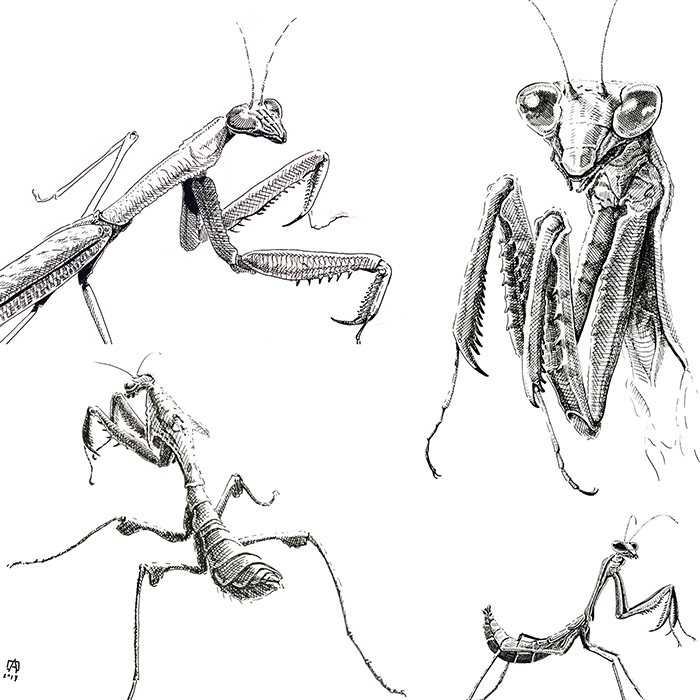

His latest work focuses on a contemporary arthropod: the praying mantis. His sketches and models show the complex machinery of mantis anatomy—mandibles, maxillary palps, ocelli—some of which he learned just for this project.

“I am obsessed with figuring out how things work,” he says. In other words, he wants to get to the bottom of things.

To see more of Drummondʼs work, visit his Instagram page, and if youʼre near Seattle in December, check out his solo show at Creatura House Gallery, opening December 6, 2018.