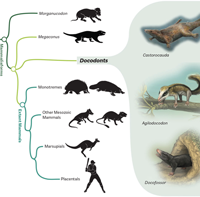

Agilodocodon is one of the earliest known arboreal and subterranean mammals. (Illustration by April I. Neander)

The discovery of two species suggests greater variety of the earliest mammaliaforms.

Mammals’ evolutionary history stretches back hundreds of millions of years, to the Mesozoic era. Dinosaurs dominated the earth then, but research increasingly suggests that stem mammaliaforms—some of which gave rise to today’s mammals—were more diverse and adaptive than previously believed.

UChicago organismal biology and anatomy professor Zhe-Xi Luo coauthored two papers in the February 13 Science on the discovery in China of the earliest known tree-dwelling mammaliaform, Agilodocodon scansorius, and the earliest known subterranean mammaliaform, Docofossor brachydactylus. Belonging to the now-extinct order Docodonta and dating back 160 to 165 million years, both provide evidence of early mammals’ wide-ranging environments and morphologies.

Docofossor, for example, looked strikingly similar to modern African golden moles: short, wide upper molars for foraging underground; a sprawling posture that suggests crawling; and shovel-like fingers for digging. Agilodocodon, meanwhile, had the curved, horny claws and flexible joints of today’s tree-dwelling and climbing animals.

The taxonomic illustration shows a few branches of the mammaliaform tree, both living and extinct, including the docodonts, with whom modern mammals share a common lineage. Alongside Docofossor and Agilodocodon is Castorocauda, a swimming, fish-eating Jurassic docodont first described by Luo and colleagues in 2006.