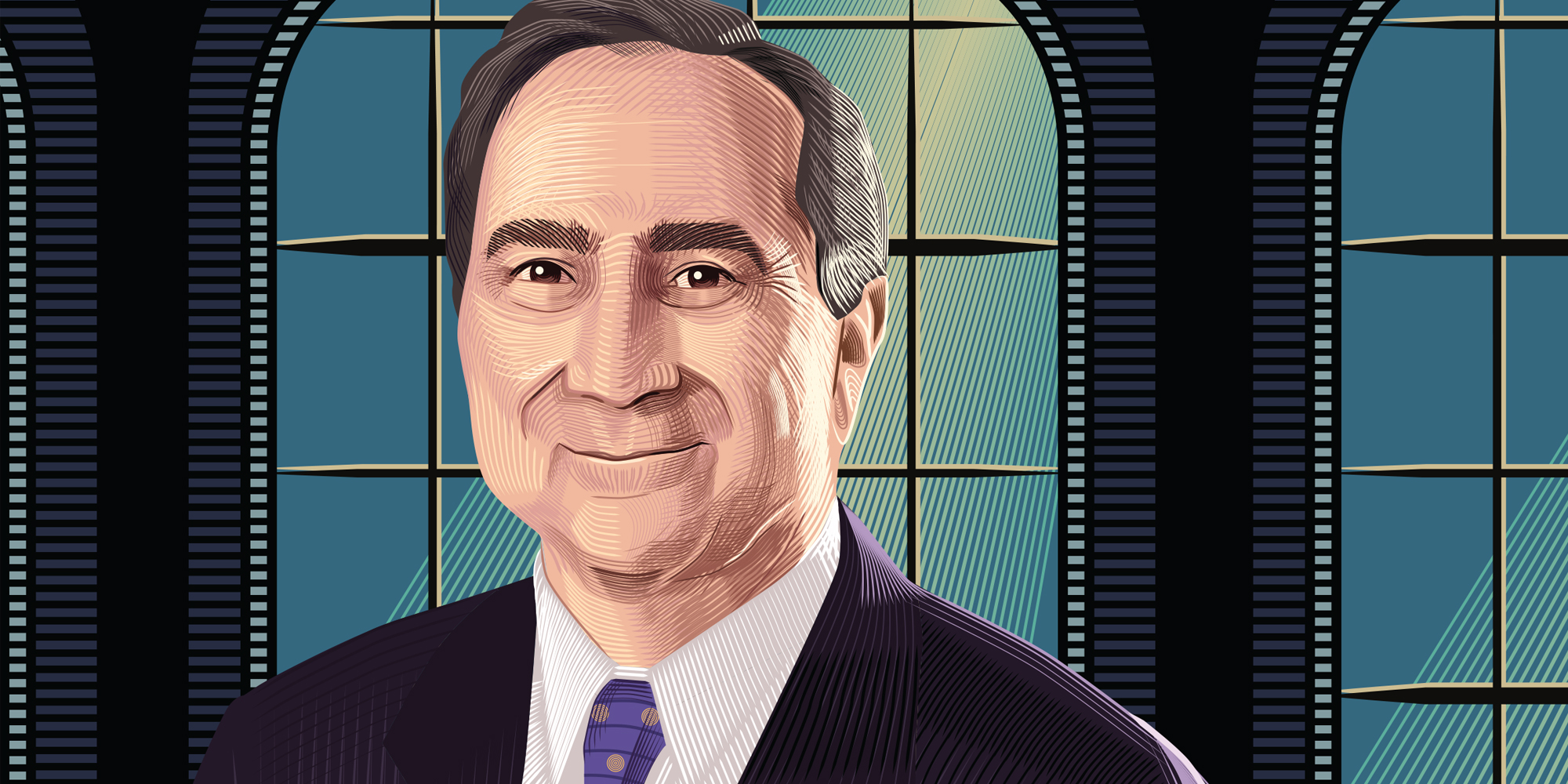

(Illustration by Daniel Hertzberg)

Remembering Hugo Sonnenschein, 1940–2021.

After stepping down as the University of Chicago’s 11th president in June 2000, Hugo Sonnenschein was asked by this publication to reflect on his tenure. In characteristic style, he didn’t mince words: “The hardest situations are the ones where there isn’t easy agreement,” he replied, “where there may be a need to do something that may not be popular. And you’re the one who has to say, ‘Do it.’”

Sonnenschein, the Charles L. Hutchinson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in Economics, died July 15, at age 80. He is remembered for a decisive approach to governance during his seven years as president, a period in the ’90s when the University grappled with addressing financial challenges while preserving its intellectual identity.

That was the “practical challenge” he faced, says Geoffrey R. Stone, JD’71, the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law, who served as provost during Sonnenschein’s presidency. “Hugo was really quite remarkable in his demand to know the facts, to understand the facts, and to do what was necessary to preserve the excellence of the University.”

An economist who had come to Chicago after serving as provost at Princeton University, Sonnenschein laid out the facts as he saw them in a famous letter to faculty dated April 30, 1996. “Our smaller number of undergraduate alumni has led over time to fewer contributors to the University and fewer dollars for the endowment,” he wrote. “A structure in which tuition does not cover salaries and in which endowment does not grow at a robust rate is not sustainable over the long term.”

Sonnenschein proposed an aggressive plan to enlarge the undergraduate College by 1,000 students over a period of 10 years. In 1998 the Council of the University Senate agreed to the expansion while making recommendations to ensure no loss of educational rigor. Later that year Sonnenschein approved reducing the number of required courses in the College’s legendary Core curriculum to allow for more electives and study abroad opportunities.

Both moves were perceived by some as watering down academic standards—and the school’s niche identity—in a bid to attract more applicants. The curriculum change, in particular, hit a nerve. A firestorm erupted among students, alumni, and faculty. Critics feared that, in restructuring the University, its founding identity as a graduate-oriented institution—a true research university—would be in peril.

John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, dean of the College since 1992 and a historian of the University (and of empires), likens the period to a sort of “revolution.” The process of amending the Core from 21 to 15 credits, plus a foreign language requirement—“very tough but still very effective,” Boyer says—took four years and endless meetings. “Hundreds of meetings. Big meetings, small meetings, proposals, and counterproposals,” he recalls. “It was like marking up major legislation, like getting the Affordable Care Act passed through Congress.”

Through it all, Sonnenschein—described by those who knew him as soft-spoken and unflappable—stayed the course. Stone says, “Hugo basically took the view that, I have to do the right thing for the University, that’s my responsibility. If it creates flak for me, I’ll deal with it.”

While conflict swirled, Sonnenschein wrapped up a $676 million capital campaign, the largest in the University’s history at the time, and instituted the first campus master-planning process in 30 years. He invested heavily in enhancements to undergraduate student life, from career support to dance studios, and more than doubled the University’s endowment.

Over the past two decades Sonnenschein’s key changes were adopted and expanded by succeeding administrations. The shifts still have their critics, Stone acknowledges. “I think you would find faculty members who would say this is not the same university,” he says. “In some sense they’re right, but we couldn’t have kept that—that was the problem.” The College, which now numbers about 7,000 students (almost double what it was in 1996), is hotly sought after by top high school seniors and has an acceptance rate that’s gone from 77 percent when Sonnenschein took office to just over 6 percent today.

Hugo Freund Sonnenschein was born November 14, 1940, in Brooklyn. His mother died when he was very young, and he was raised by his aunt, who, he later recalled, “cared about what I would become and valued education.” In 1961 he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from the University of Rochester, where he met his future wife, Elizabeth Gunn. The two married in 1962 and had three daughters: Leah, Amy, and Rachel.

While at Rochester, Sonnenschein discovered a paper on “social choice” and the work of Kenneth Arrow, which ignited his love of economics. He rocketed through his graduate studies. By the time he was 23, he had completed his doctorate in economics at Purdue University.

His brilliance was apparent early on, says Sonnenschein’s colleague and former doctoral student Philip J. Reny, the Hugo F. Sonnenschein Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and the College. “Hugo’s approach to consumer choice theory has since become a standard in the field,” and the effects of his most stunning and important result—the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorem—“ripple through economic theory to this day.”

Sonnenschein taught economics at several universities, including Northwestern and Princeton. In 1988 he became dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania before returning to Princeton as provost in 1991. Reny, his doctoral student at Princeton during the 1980s, recalls a gifted and gregarious mentor whose “office hours” often took the form of a walk across campus to get ice cream.

Sonnenschein was an equally talented lecturer. In one particularly memorable presentation, he performed a sort of dance to demonstrate subtleties in consumer preference relations. Crouching in the corner of the lecture hall, he used elegant sweeping motions of his hands and arms to trace the surfaces of two indifference maps as he rose and moved toward the center of the room. “The distinction instantly became clear to me,” Reny recalls.

That gift for connecting with students continued during Sonnenschein’s presidency. “One day he and I were talking about how to engage the undergraduates in a more natural way, instead of ceremonial visits to dorms,” Boyer recalls. Sonnenschein, a cyclist, suggested a bike ride.

Fifty students showed up and cycled with the University president and dean of the College seven miles up the lakeshore. “Hugo didn’t look so presidential in his bike helmet and gloves,” Boyer muses, “and we said to ourselves, ‘we’re not sure William Rainey Harper would have done this.’” But the outing was a success and set the tone for the president’s easy, informal style.

After Sonnenschein’s presidency and a yearlong sabbatical, he resumed his teaching and research in the economics department. Soon after, the department chair stepped down. When volunteers to fill the post were not forthcoming, Sonnenschein raised his hand.

“I don’t know that many individuals would be able to go from university president to department chair,” Reny says. Sonnenschein was not only happy to perform this “selfless act,” he recalls, but “did it with such grace, purpose, and with a genuine spirit to help others.”

Mary Abowd is a writer and editor based in Columbus, Ohio, and formerly worked in the University of Chicago News Office.