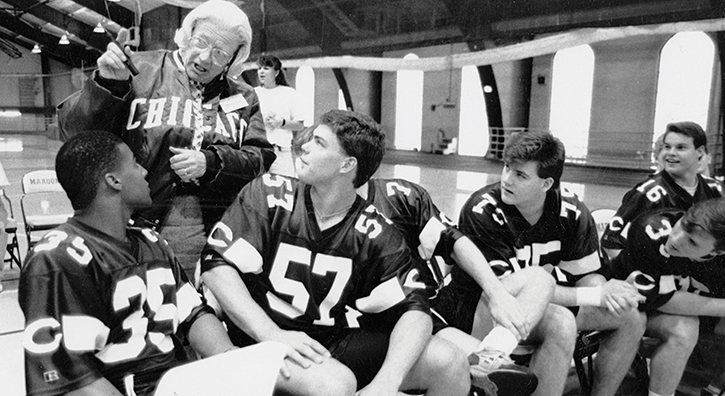

Gray coaching UChicago football players for a charity Monsters of the Midway competition against the Chicago Bears, 1992. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Thoughts on academia, football, and that painting.

Hanna Holborn Gray, who served as the University’s president from 1978 to 1993, is the Harry Pratt Judson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History. (Not emerita, emeritus. “That’s just good Latin,” she says.) Gray was interviewed for the College Memory Project in April. The transcript from the conversation has been edited and adapted below.

Barbarian

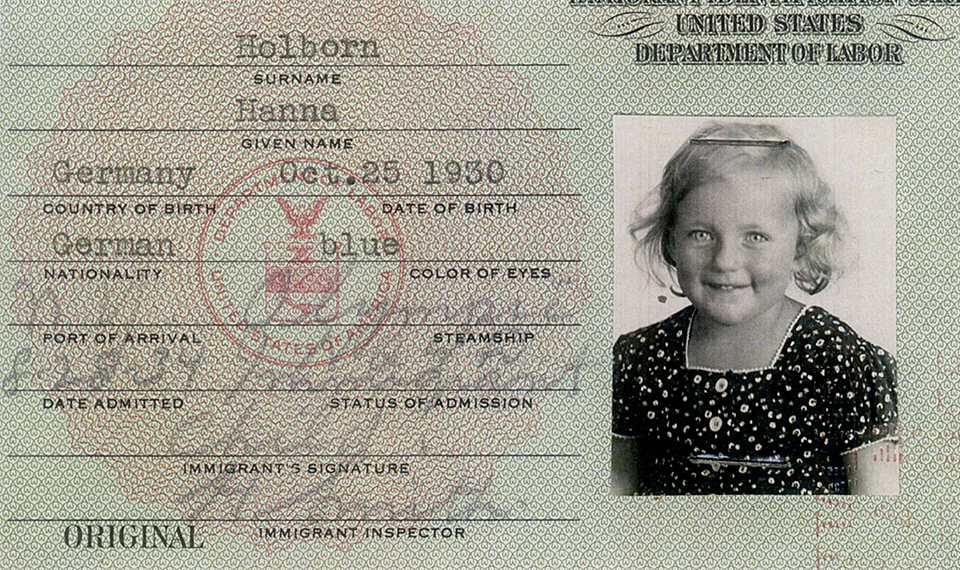

I grew up in an academic environment. My parents [historian Hajo Holborn and philologist Annemarie Bettmann] had left Germany after Hitler came to power. There was a considerable emigration of professors after April 1933 [when Jews were banned from universities] and again after Kristallnacht in November 1938. My father lost his university position in Berlin when Hitler’s regime dismissed all civil servants who were politically unreliable or Jewish. My father was certainly politically unreliable and my mother was Jewish. They saw very clearly what was happening in Germany.

At that time you could leave. In fact, the regime was very anxious to have as many politically unreliable and Jewish people leave Germany as possible.

So I grew up in a household that was not only academic but European. My parents loved America, the freedom, the greater informality, the academic world, but they did not like American popular culture. We were not allowed to listen to the radio and we were not allowed to eat a lot of stuff that they thought was barbarian, like Wonder Bread.

Academics

Growing up in the household that I did [in New Haven, Connecticut], everyone I knew was an academic. My grandparents were academics, my parents were academics, and it was the last thing I was going to be or do.

In college [at Bryn Mawr] I had a sort of epiphany one night when I went to the library. There was something about the atmosphere and the way in which the library projected itself on one: creaking wooden stairs, a certain musty smell of books.

I thought I could really be happy doing this every night of my life.

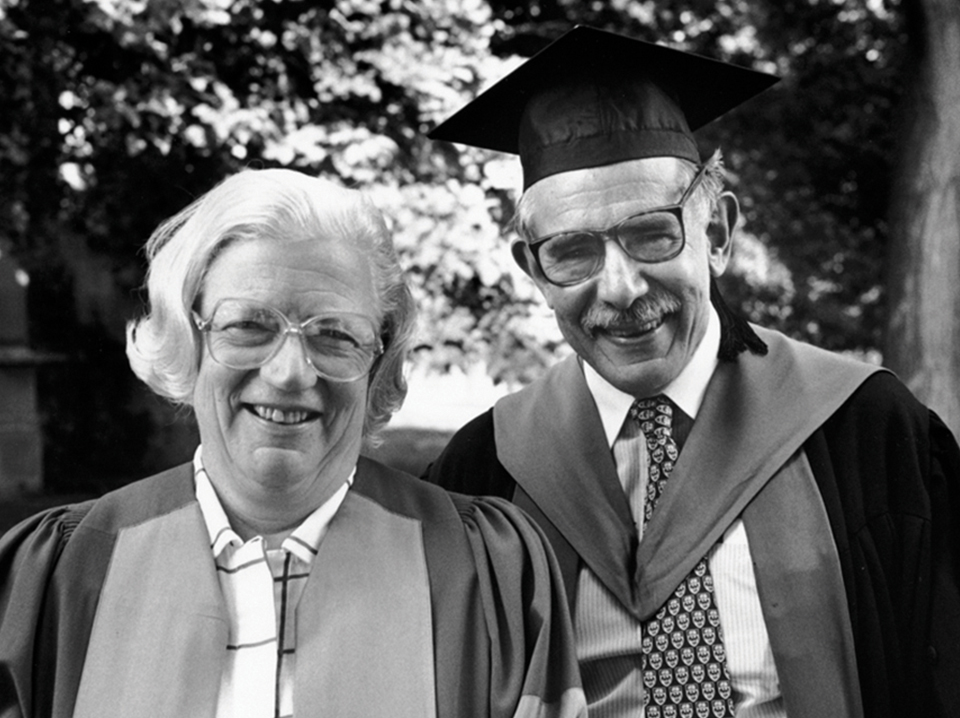

When I came to Chicago with my husband [legal historian Charles Montgomery Gray, 1928–2011] in the fall of 1960, I thought my career was probably over. Institutions didn’t appoint husbands and wives, particularly if they were in the same field.

The first year that we were here I had a fellowship at the Newberry Library, which has a wonderful collection of Renaissance humanism, my area of specialization. I was also asked to teach a section of Western Civ, which at the time was required for all College students. I guess the University was trying me out. I was offered a full-time job the following year.

Unusual

I thought the students were unusual. I had been an assistant professor at Harvard, where some of the students had no intellectual interests at all, so far as I could tell. Here all the students seemed to want to be intellectuals, and they were all studying the same texts, so they were talking to each other about the ideas they were coming into contact with.

That was wonderful for a teacher, that kind of focus and intensity.

I came back in the late ’70s at a time that was difficult for all universities. The University was not rich, to put it mildly. I had always felt that the College could be larger than it was. When the College was around 2,400 students, they felt submerged in the University rather than the masters of the University, which undergraduates should be.

It was also the time—this is not something that’s totally changed—when those T-shirts said, “University of Chicago: Where fun has come to die.” I thought that maybe we could lighten up the place a little bit for students without diminishing the intellectual seriousness, so I gave a party for the College. We took over Ida Noyes; we had different bands on each floor and so on. At the end, a student came up to me and said very politely, “Thank you, that was a very nice party.” Then she glared at me and she said, “I hope you’re not going to try to make this a fun place.” I felt, that is your University of Chicago student. On the other hand, the major vituperation I experienced, among many vituperations, was when I shut down the Lascivious Costume Ball.

When I was president, I was interviewed by the New York Times. I said, and they published this, that I thought I was the only University president in the country who did not know that the football coach had left until my Christmas card came back and it had a big stamp on it saying: “Moved: Left no forwarding address.”

My favorite tradition was the convocations in Rockefeller Chapel. There’s a dignity and beauty about the ceremony that I always enjoyed. Each time I saw that student in front of me, to whom I was going to hand a degree, it was a joyful occasion.

Terrible

I’m not a fan of my portrait [in Hutchinson Commons]. I feel it makes me look meaner than I am. I certainly appreciate the fact that the trustees at the time thought that they would get a good modern artist to paint a portrait.

Unfortunately, the artist they got was a man who particularly likes to paint nudes, and that was not the task here. And then, of course, it stood out in that room in the most terrible way. It was kidnapped twice, and I thought it was a pity it was recovered. I think it’s now so wired up that you’d probably be electrocuted if you got too close.

Watch the videos, produced by Valerie Archambeau and Benjamin Chandler, AB’04.